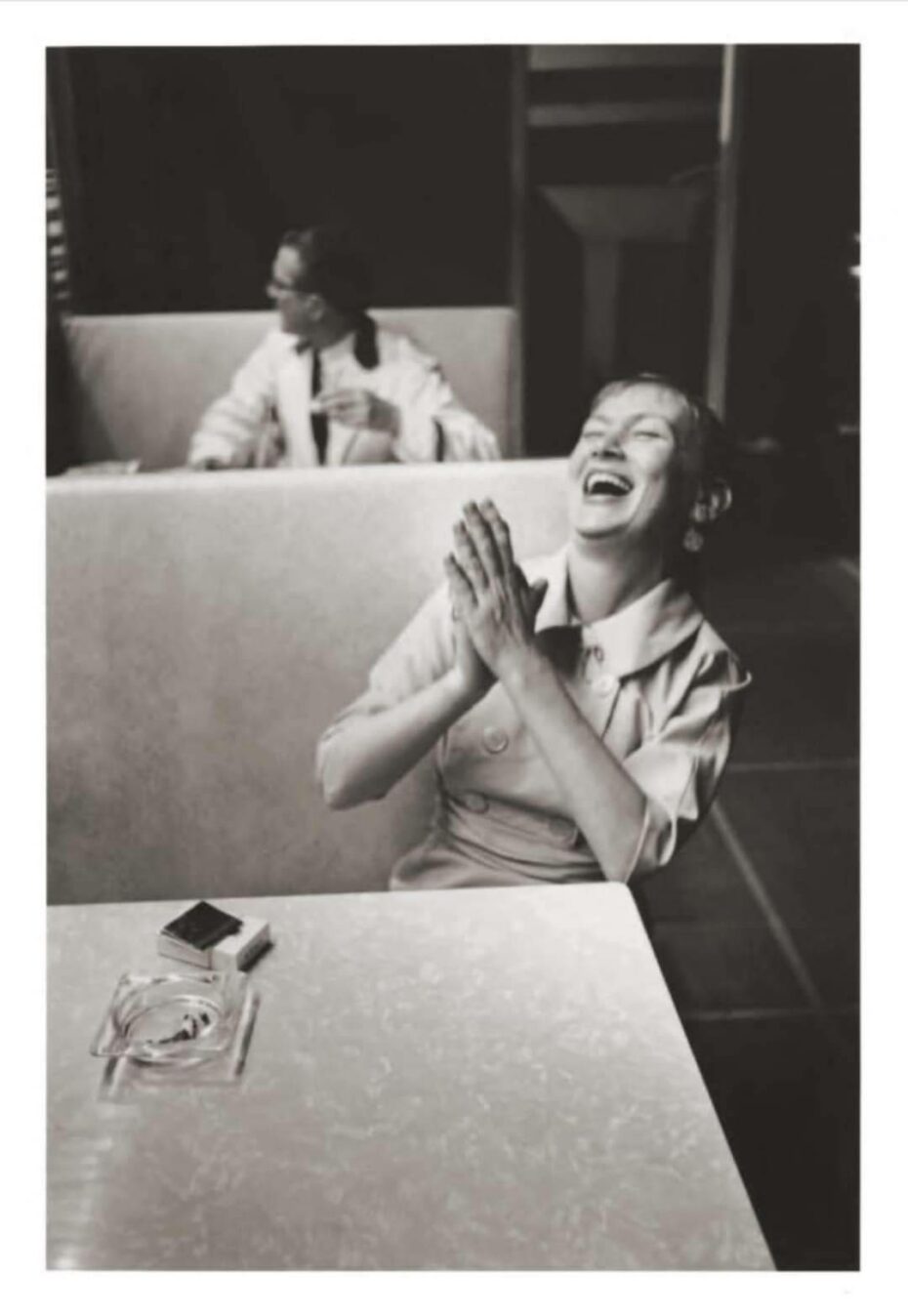

In 1962, a reporter with the New York Post got a tip that screen goddess of the 1940s, Veronica Lake, was working as a barmaid in the lobby of the Martha Washington Hotel, a low rent boarding house in Midtown Manhattan. Using the name Connie de Toth, she said she enjoyed her job because “I like people. I like to talk to them.” When the news article broke portraying her as a destitute ageing screen legend, fans sent money but Lake sent it back. She was offered a deal to publish a memoir, Veronica: The Autobiography of Veronica Lake, in which she recounted her career as the film noir queen, describing herself not as a “sex symbol” but a “sex zombie”. So how does a household name end up working in a transient hotel? As much as we love dive bars and quite frankly, wouldn’t mind spending the rest of our days talking to local eccentrics and wise old timers over drinks, there’s something undeniably unsettling about celebrities who end up just like the rest of us. But it’s a tale as old as the Hollywood Hills, particularly for women, and one that despite us entering what appears to be a new era of visibility for ageing femininities, is still very much a relevant topic of conversation.

Born Constance Keana, Veronica Lake, a nickname given by producer Arthur Hornblow Jr. because her eyes were “calm and clear like a blue lake”, found success as a teenager with the military drama I Wanted Wings. At her peak, she was considered one of the most reliable box office draws in Hollywood. Lake became a style icon known for her peek-a-boo bang look, and the hairstyle became so popular during WW2 that the U.S. government asked her to change it to something more suited for factory work. She soon obliged and unveiled her new look: the victory roll.

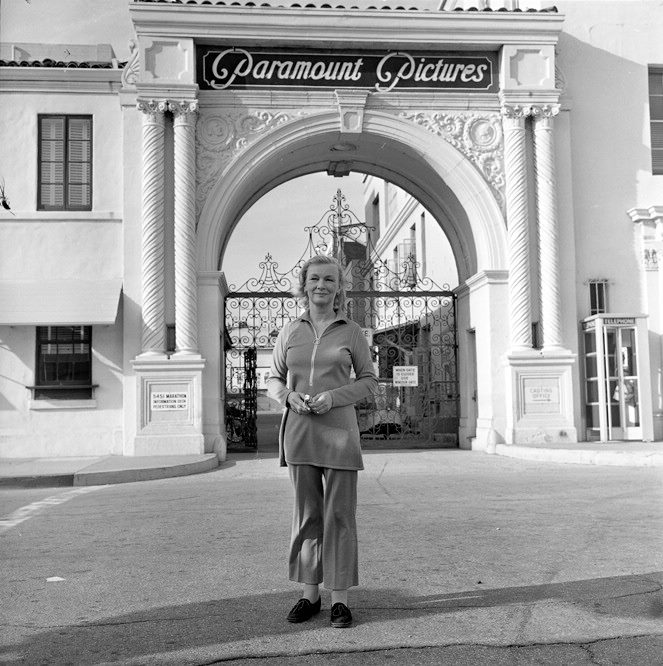

She toured the country extensively during World War II to promote the war effort but while filming Sullivan’s Travels in 1941, she was six months pregnant, and tried to hide this from the director, Preston Sturges. He became so enraged that he had to be physically restrained. It was around this time that she started to develop a reputation for being hard to work with on set. In 1943, she tripped over a cable on set and went into premature delivery of her second child, who died shortly after child birth. Within a few weeks, she had filed for divorce from her husband. When she returned to work in 1944, she publicly expressed hopes for a turning point in her career, saying that the roles she had played thus far, “haven’t been noteworthy […] From here on there should be a certain pattern of development, and that is what I am going to fight for if necessary, though I don’t believe it will be because they are so understanding here at Paramount.”

Behind the scenes, Veronica had started to drink heavily as she coped with the personal tragedy of losing her child. A faltering career, bad press and negative reviews only exacerbated what would become a growing struggle with alcoholism. In 1948, Paramount opted not to renew her contract. In 1951, her second husband filed for bankruptcy and the IRS later seized their home for unpaid taxes.

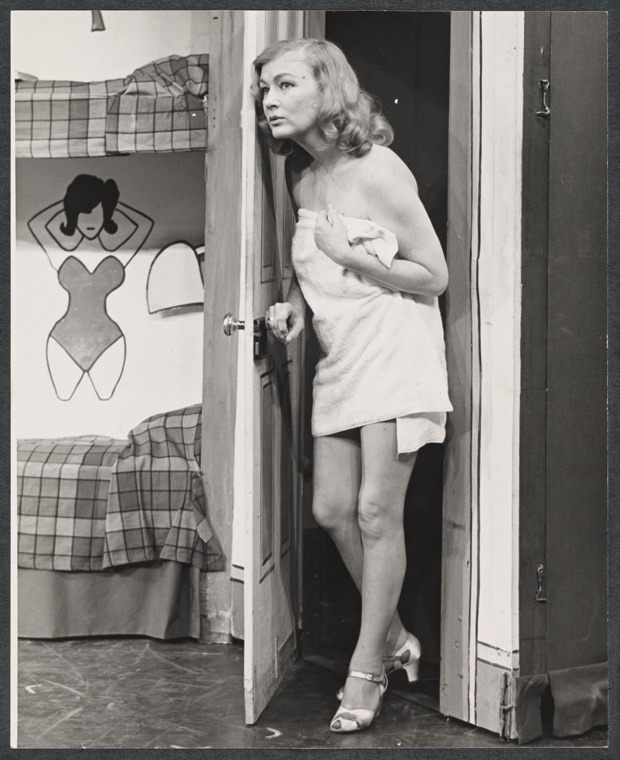

She eventually ended up taking theatre roles, and after three divorces, was drifting between cheap hotels in New York City. On more than one occasion, she was arrested for public drunkenness and disorderly conduct. Veronica had a complex personality. She had a pushy stage mother who later claimed that her daughter was diagnosed with schizophrenia at age 15. Sadly, she continued to be impacted by alcoholism and died at age 50 in 1973 of acute hepatitis and acute kidney injury. In 2004, some of Lake’s ashes were reportedly found in a New York antique store.

On a lighter note, today the Motion Picture & Television Fund provides a sort of retirement home where retired TV and film professionals from in front of the camera & behind it can reside in cottages (funded by actors including George Clooney), and live amongst a community of ex-entertainers and even run their own closed-circuit TV station. But the recent Hollywood strikes have starkly demonstrated the widespread precarity in “the dream factory” that is the movie industry. Even some of the most famous stars have found themselves back in the “normal world” after their star burned out. Unsurprisingly, this has particularly been the case for women, notably during Hollywood’s golden age, as their value has long been placed more on their looks than other talents.

Louise Brooks was the embodiment of the flapper, even helping popularise the style’s classic bob hairdo. Brooks began her career as a dancer and was discovered by a Paramount Pictures producer while performing with the Ziegfeld Follies, an extravagant theatre review. One of her first big roles was in 1928’s Beggars of Life, an early sound film in which she kills her abusive stepfather and is on the run from the law dressed as a man. (The story sadly mirrored Brooks’s own rural childhood and sexual abuse, which would have long-term impacts on her mental health). Within a decade, she had acted in some 17 silent movies and eight sound ones.

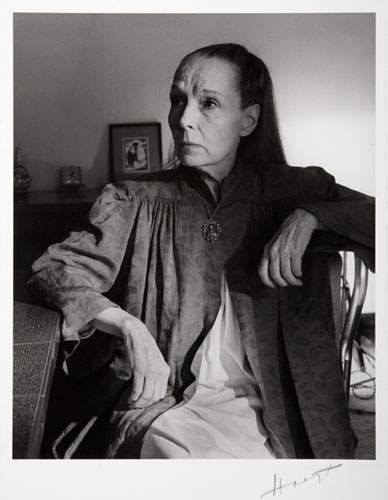

But Brooks struggled as an independent spirit in the sexist Hollywood system and was particularly impacted by the suicide of her one-time lover and close friend, Pepi Lederer, who had been committed to an asylum, either for her sexuality or drug addiction. Brooks and her naturalistic acting style instead flourished in the relatively free and cosmopolitan city of Berlin during the Jazz Age. She became a star there for her role as Lulu in the German silent film Pandora’s Box, one of the first onscreen portrayals of lesbianism. (She even beat out Marlene Dietrich for the role.) She returned to Hollywood but either turned down roles or faced blacklisting. She declared bankruptcy in 1932 and returned to dancing in clubs. She had one last big role, as the love interest for John Wayne in Overland Stage Raiders (1938), but now with a long hairstyle, she had lost her unique looks and edge. She went on to take on a range of gigs: copywriting for a magazine, attempting to run a dance studio, writing a gossip column and even being a salesgirl at Saks Fifth Avenue in Manhattan. She eventually became a high-class courtesan in the late 1940s, a time in which she often contemplated suicide, as she recounted in her memoir.

When asked by a journalist in her last years why she thought she never got on in Hollywood, she shrugged and said, “I liked to fuck and drink too much.” Luckily, French film historians like Henri Langlois helped promote a rediscovery of her work, prompting a Louise Brooks film festival in 1957. Her likeness also continues to be an inspiration, appearing in films ranging from Cabaret to Death Becomes Her to Mixed Nuts.

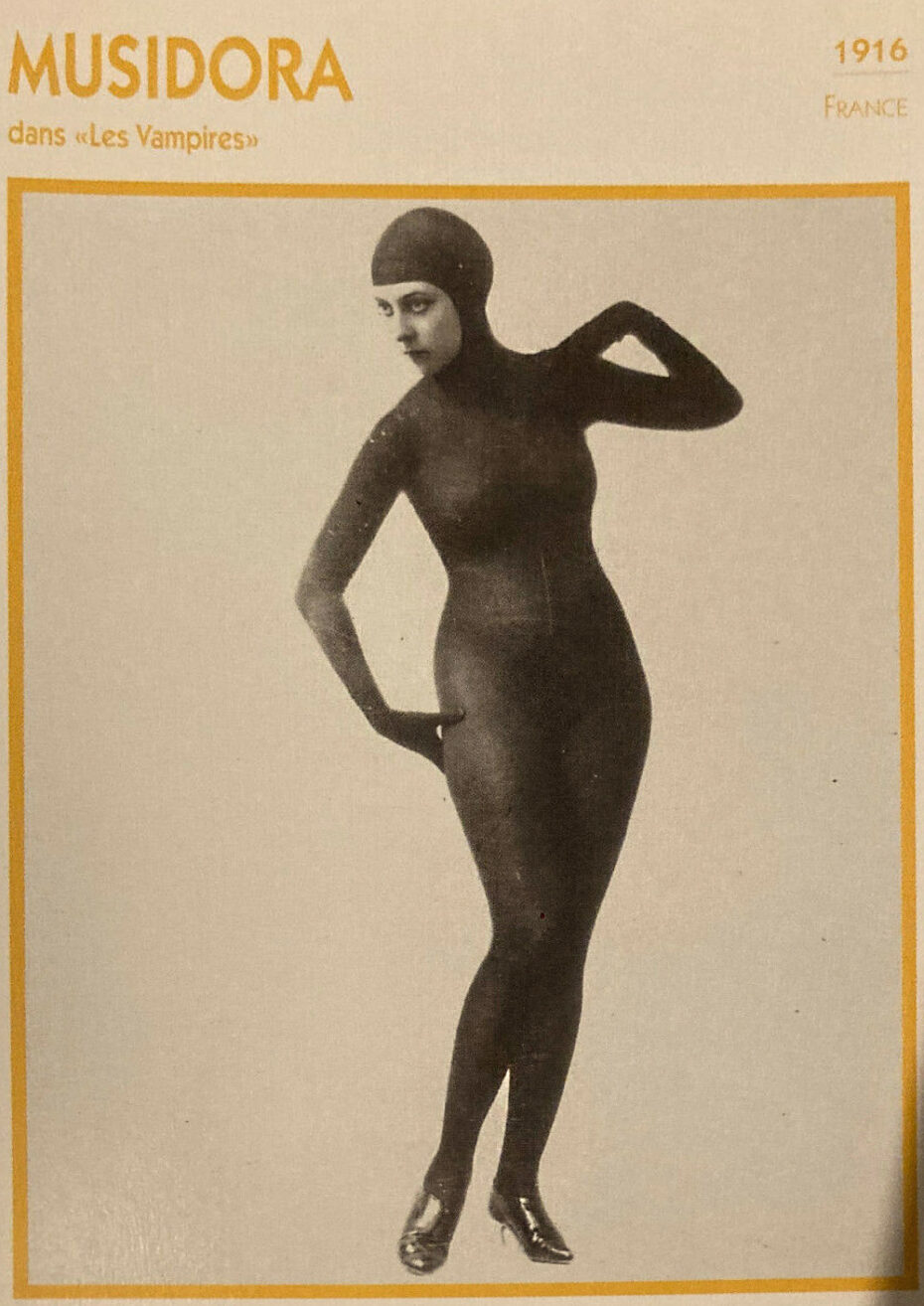

The story of ageism and fallen or reclusive celebrities is not unique to Hollywood, of course. Case in point: the famed and forgotten French icon, Jeanne Roques, who became famous under the stage name Musidora, flexing her feline curves in skin-tight lycra all-in-ones, eons before Catwoman ever came to screen. She became a celebrity almost a decade before Louise Brooks in 1915, when she starred in the black-and-white silent movie Les Vampires (1915) as the slinky cat-burglar, Irma Vep.

To this day, Les Vampires, is regarded as one of the most influential crime films of all time – one of the lengthiest too, at 7 hours. Her public profile was swiftly discarded however when the 1930s talking pictured changed the world of cinema. Toward the end of her life, she took a job as a film historian at the Cinémathéque Française, one of the few places that was keeping alive the heritage of French silent cinema. She would also occasionally work in the ticket booth. Few cinema-goers realised the older woman who sold them their cinema ticket was also starring in the movie they were watching.

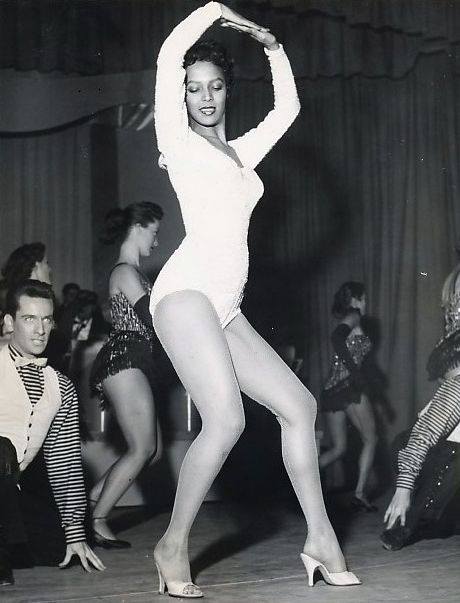

Fame has long been described as a fickle mistress, showering adoration, success and all that comes with stardom one day and then gone the next. Dorothy Dandridge stands out as the first African-American woman to be nominated for an Academy Award for Best Actress (for the 1954 film Carmen Jones). Her first starring role was in the 1953 low-budget film Bright Road, which also marked her first time acting alongside Harry Belafonte. They appeared together again in Carmen Jones, an all-Black retelling of the opera Carmen. Despite the fact that her singing voice was overdubbed by a white opera singer, Dandridge became a global star with the hit film, becoming the first African-American woman to appear on the cover of Life magazine. She also paved the way for other Black artists and was active in Democratic politics as a member of the National Urban League and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. However, she still faced much discrimination, particularly around starring in any romantic role, and particularly, if her onscreen paramour was white.

Her realities of private life were equally less glamorous. Her husband was a womaniser and heavy drinker, and after enduring a difficult birth alone in 1943, she was left to raise their mentally disabled daughter largely as a single mother while trying to manage her career. She later remarried, to a white nightclub owner who beat her and ruined her financially. Cast out of Hollywood, her star had dwindled by the early 1960s and she was forced to give up her home in Los Angeles. Plagued with guilt for having to put her daugter in a state funded institution, she began to drink and became addicted to prescription medications. Things briefly looked up when she reconnected with her former Hollywood agent and returned to her roots, performing as a lounge act in Las Vegas in 1964. But when she twisted her ankle on stage, she once again found herself out of work.

In 1965, at the age of 42, Dandridge was found lying dead on the floor of her bathroom by her agent. From the book Tragic Hollywood Beautiful Glamorous and Dead:

“The coroner’s report cited the cause of death as a rare embolism that occurred when pieces of bone marrow broke off from her fractured ankle and lodged in her lungs and brain. Interestingly, the toxicology report painted a different story. Accidental overdose of the anti-depressant Tofranil was listed as the cause of death”.

Tragic Hollywood Beautiful Glamorous and Dead

Growing up during the Great Depression with a bootlegger mom, Elizabeth June Thornburg, aka Betty Hutton, honed her craft from a young age performing in the speakeasy her mother ran out of their home. Thornburg was discovered by a bandleader while performing in Detroit nightclubs and developed a unique “whoop and holler” vocal style. After appearing in a series of Warner Bros. shorts and Two for the Show, a musical review on Broadway, she got a contract with Paramount Pictures. Her fame continued to rise into the ‘50s, when she took on the role of Annie Oakley in Annie Got Your Gun (replacing Judy Garland), starring with Fred Astaire in Let’s Dance and performing as a trapeze artist in the star-studded The Greatest Show on Earth, an epic by Cecil B. DeMille that won the Academy Awards for Best Picture and Best Story. But by the time she was in her 40s, her career was in sharp decline, and the media attributed her clashes with Paramount Studios to her struggles with chronic depression and addiction, exasperated by her mother’s 1962 death in a house fire, as well as several divorces. After a failed comeback, she found peace in religion, converting to Catholicism and working as a cook and housekeeper at a Rhode Island rectory. In 1978, she reappeared on the Donahue to explain what she’d been through:

Caroline Young’s book, Crazy Old Ladies: The Story of Hag Horror tells the story of the ‘hag horror’ sub-genre of cinema, which cast former queens of the Golden Age of Hollywood, transforming them into grotesque caricatures that revealed a cultural disdain for older women. “The films were almost saying ‘look what will happen to you if you decide not to get married or have children.’ They were driven mad by their single status and their lost looks, and this was the trope in hag horror. They were depicted in wheelchairs, or with a walking stick, they kept cats around them, or boxes of mementos from their past”, explains Young. The irony is, for women, a career in Hollywood too often came at the expense of having the traditional family life that it glorified on screen. In her autobiography, Veronica Lake notably talked about the guilt she felt over not spending enough time with her children. “The actresses who played these parts often lived beyond their gender expectations, despite the promotion of their beauty and glamour as an aspiration for regular women,” explains Young.

Names like Meryl Streep, Jennifer Coolidge, Michelle Yeoh and Judy Dench give us hope, but how far have we really come? As an article on Refinery 29 points out, when Meryl Streep turned 40, she was offered the role of a witch three times in the span of a year. According to a study by the Center for the Study of Women in Television and Film at San Diego State University, men over 60 made up 10% of characters while women 60 and over made up only 6% in 2020. A 2021 Nielsen report found that while women over 50 make up 20% of the population, they are still only portrayed on television 8% of the time, and their stories often revolve around motherhood. A 2023 study from the Annenberg Inclusion Initiative found that of the 44 movies in 2022 that featured women as leads or co-leads, only 10 of these films starred women over the age of 45. Also, the average age of female Oscar winners for acting categories is 39, while the average male actor’s age is 47. As an Oxford University Research hub argues, the women we choose to celebrate are “only the ones that appear ‘ageless’, age in the ‘appropriate way’, and those that promote themselves through an association with success in later life and who conform to neo-liberal ideas about ageing well: In other words, the ones that are ageing youthfully.”

To help tackle this double standards of aging for women, actress Geena Davis had been one of the leading voices in Hollywood working to get more female roles in movies and TV. Back in 2004, she founded the Geena Davis Institute on Gender and Media back in 2004, not just to help women in film, but women everywhere, particularly those over 40, who are hungry to see themselves represented on screen in a positive way. Sharing the stories of older women, celebrating their wisdom and complexities, will slowly chip away at old stereotypes, reminding future generations what Michelle Yeoh told us in her 2023 Oscars acceptance speech: “Ladies, don’t let anyone tell you you are ever past your prime”.