MacDonough Street looks much the same as any street in Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood; long and leafy and residential, with historic townhouses neatly arranged in rows, punctuated by the occasional larger building. But one of those larger buildings – 87 MacDonough Street – stands out.

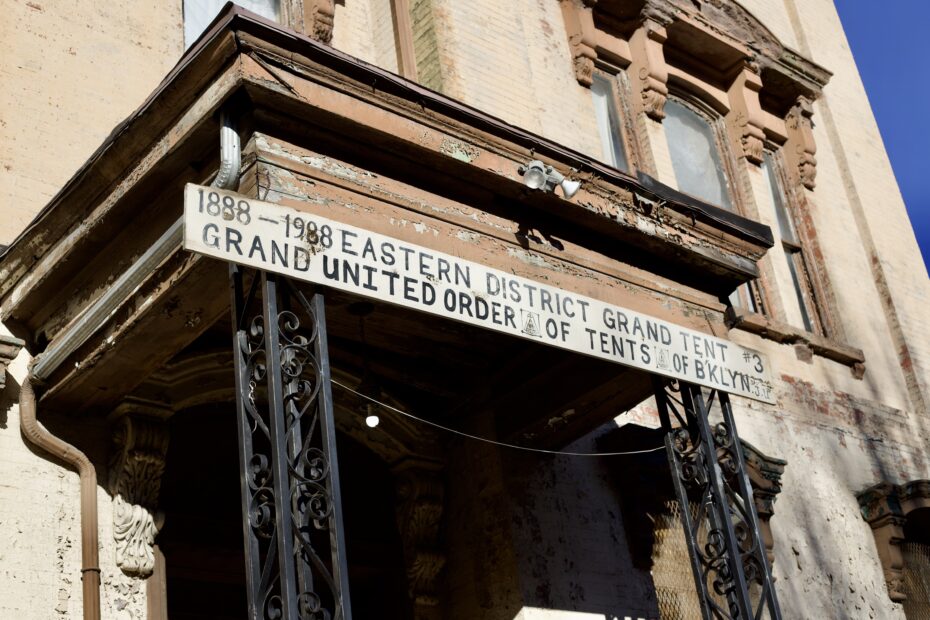

Although today its windows are boarded, you can see the grandeur in this freestanding structure, a nineteenth-century mansion originally built as a home for a wealthy brewer, with a tower to one side that looks almost like a turret. This is a building fighting for its life, and as it turns out, the historic headquarters of a little-known religious and philanthropic organization with a heritage dating back to the Underground Railroad. For years, 87 MacDonough Street served as the “Grand Tent” of Eastern District 3, the headquarters of the northeast branch of … [checks notes] … the United Order of Tents. Intrigued? So were we… (particularly after that Egyptian UFO-cult we tracked down in Brooklyn).

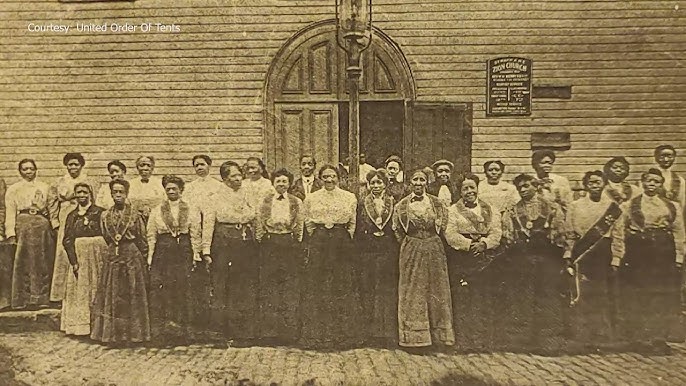

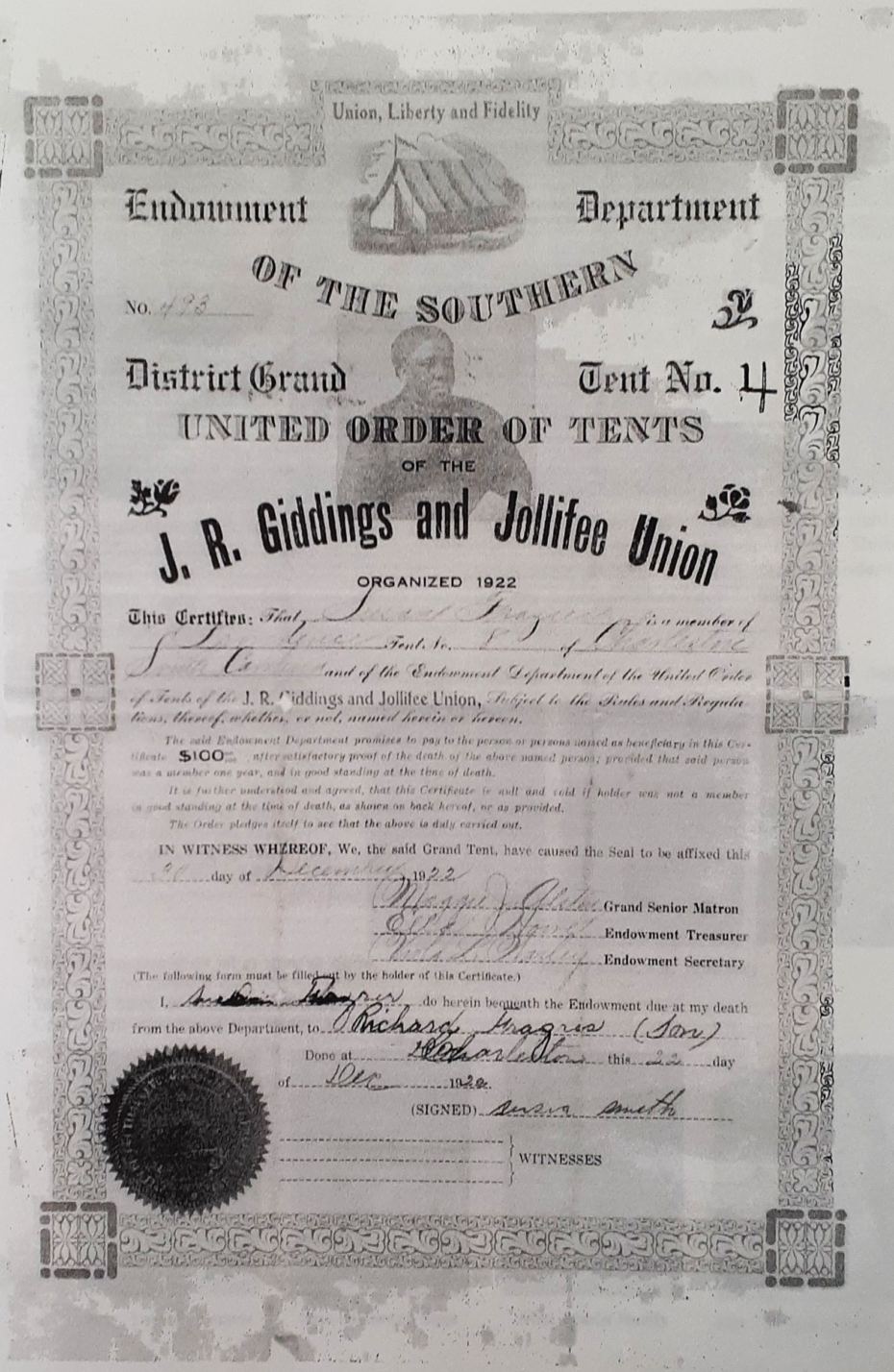

Although MacDonough Street is in Brooklyn, the United Order of Tents began hundreds of miles south of New York, in Norfolk, Virginia as a sisterhood for Black women. There, in 1867, two formerly enslaved women, Underground Railroad agent Annetta Lane and Harriet R. Taylor, founded a Christian mutual aid organisation with the help of local abolitionists, with the intention that it would serve as a source for medical care, elderly care and burial services to members of the community in need. (Annetta Lane was a nurse, and it was this position, and the movement it allowed for, that had enabled her to become involved with the Underground Railroad prior to Emancipation). To this day the organisation receives grants from the Department of Housing and urban Development (HUD) to support their housing initiatives for the elderly.

The United Order of Tents would also function as a loan society for those whose custom was refused by banks, and provide food and shelter to the needy. Their name is not rooted in a physical tent, but in the concept of being a “tent of salvation“, not only in the religious sense (although the group does identify as a Christian organization), but also as a place of refuge and empowerment for Black American women following Emancipation.

From its Norfolk roots, the Tents (as they’re sometimes called to this day), would expand across the East Coast, with four chapters known as “districts” from Maine (the northernmost point of Eastern District 3) to South Carolina (the southernmost state to be encompassed by a district–Charleston is still home to a substantial presence of the Tents and serves as a major hub within Southern District 1). Throughout their expansion, they would maintain an air of mystery, with initiation rites and rituals that remain a secret to this day.

At its height, the United Order of Tents held roughly 50,000 members, but membership has since declined, with only a few dozen women in the once far-reaching Eastern District Three. With so-called “fraternal orders,” as the Tents have sometimes described themselves, in decline across the nation, the waning interest cataloged by social researchers like Robert Putnam, the United Order of Tents was not immune.

It can be tempting to view the Tents as a kind of Black American women’s Freemasonry. The parallels are hard to miss – a secretive society with religious and philanthropic leanings, a grand and mysterious building where they gather, and a storied history doing battle with an uncertain future. But to reduce them to this would be to misunderstand not only their past, but where the Tents are steering their future.

The mansion at 87 MacDonough has been boarded up for some time – according to a 2022 piece by the New York Times, a potential tax lien and other financial woes have plagued the Tents, who have not yet given up on saving their historic home.

It is not inaccurate to call the United Order of Tents a secret society – even in the Times piece, one of the members interviewed (military veteran and member of the Tents for over 20 years Essie Gregory) politely demurred when asked about her initiation. However, unlike many secret societies, and unlike the common pattern for fraternal orders of the twenty-first century, the United Order of Tents has recently begun drawing attention to itself, and recruiting new members.

The Tents marked their 150th anniversary in 2017 in high style, with a formal banquet in a room full of “the language of roses”, but across the country have turned to educational programs, community events, like an introduction to the society held at Brooklyn Library, and even social media – yes, the United Order of Tents is on Instagram. Not only that, but the Tents have, as of the beginning of 2024, raised over $200,000 on GoFundMe to save the MacDonough Street headquarters and help keep the United Order of Tents alive.

Although the mansion is not currently in use, the memorabilia and documents of over a century and a half of the United Order of Tents are stored inside. Old china, furniture, and “gold plaques and fading photographs of women in robes” lay inside – the robes being ceremonial dress for the Order. The Times reports that the women of the Tents hope one day to open a museum, but first must save their headquarters.

For now, though, the Tents are preserving their history, and looking to build on new interest in the organization. In a way, the philanthropists who have been serving their communities together, going almost unknown for a century and a half, are doing what they’ve always done; quietly turning to the task at hand, with a patient eye towards tomorrow.