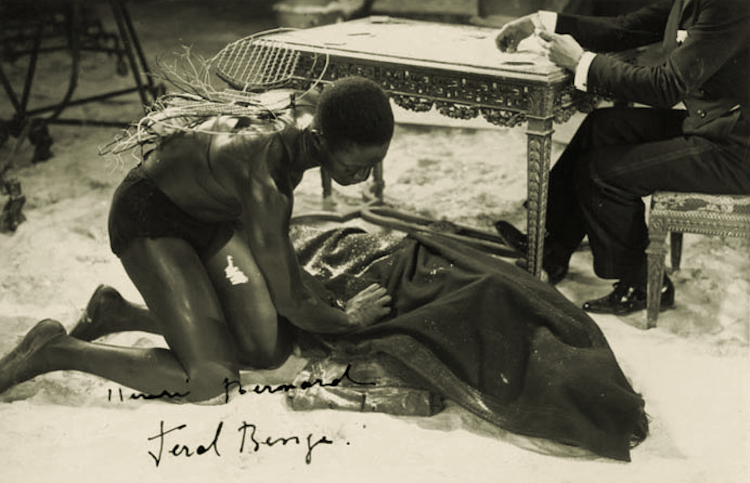

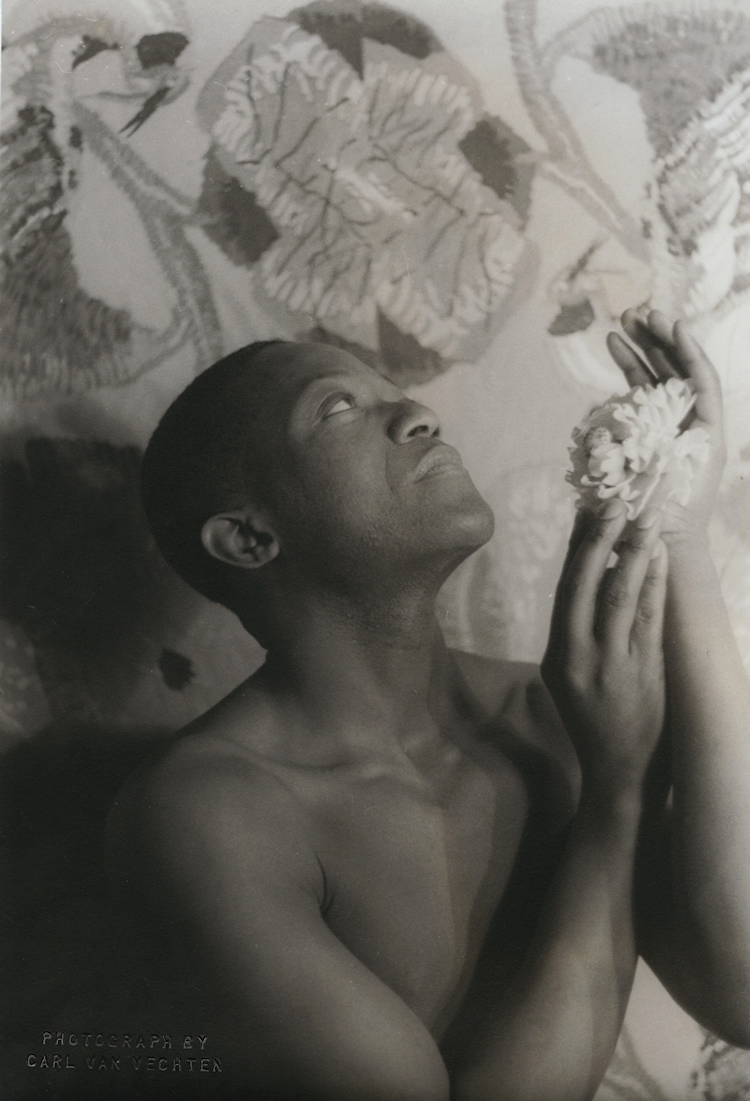

François ‘Féral’ Benga glances at us from black-and-white photographs, immortalised in a sculptural pose, large soulful eyes turned skywards as if to say, I am indeed a celestial creature. Hard to believe, but this lithe of limb and cacao-butter-sleek heavenly vision of a man was in fact an earthling from Dakar, Senegal, who used his charm and talent to carve out a niche in the 1920s and 1930s thespian society of the Harlem Renaissance in Manhattan and Harlem-on-the-Seine.

He was a film actor, performer, choreographer, dancer, nightclub owner, gay icon and the poster boy of the Harlem Resistance movement, but intriguingly everything we know about François Benga has been pieced together by what those around him remembered and created – he himself left no primary clues – no writing, no memoir, no journal or diary. It’s secondary sources – lovers, co-workers, painters, sculptors, photographers and the likes – colonial fantasists included – who have told snippets of the story we’ve pieced together of this charismatic man. We know that he started life as the illegitimate grandchild of a property tycoon and that when visiting Paris at age 17 with his father, he straightaway clocked the untapped potential for someone of his background and looks in French circles. He may also have realised that being a young gay man liberal Paris was a very different experience to being one in Harlem, where being Black and gay was isolating in an already isolated world. He parted ways with his father (who had disowned him) and worked at odd jobs with the eye on making it big in the city, which he did when landing a dance position in the chorus at the Folies-Bergere in Paris.

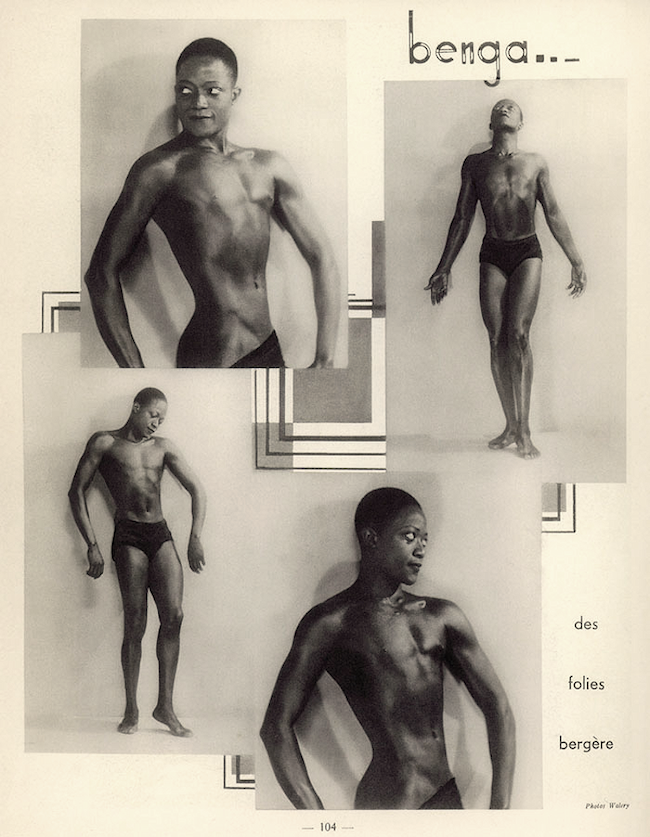

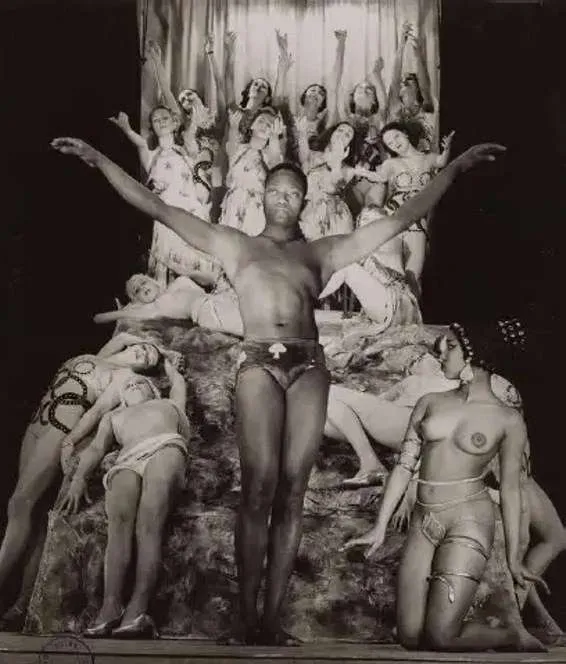

This was the moment François would become “Féral”, meaning ‘untamed’ in French, a name likely bestowed upon him by the white talent agents around him, with an audience who’d soon enough be eating out of his hand. And looking at this narrow-hipped, broad-shouldered dancer, one understands how Paris audiences found his outlandishness irresistible. When François exploded onto the Paris music scene, jiving with icon and civil rights activist Josephine Baker doing the ‘Danse Sauvage’ at the Folies-Bergere, Parisian audiences were already primed for, and embraced the eroticised racial stereotype of colonial fantasy and the ‘exotic primitives’. They simply couldn’t get enough of the hypnotic rhythm and energy radiating from the pair. Their titillating ‘sexual’ dancing reinforced the insatiable obsession European audiences had with African performers at the time – she, the ultimate uninhibited ‘ebony Venus’ in a skimpy banana skin tutu, he the impossibly virile ‘Black Mercury’ in a loin cloth.

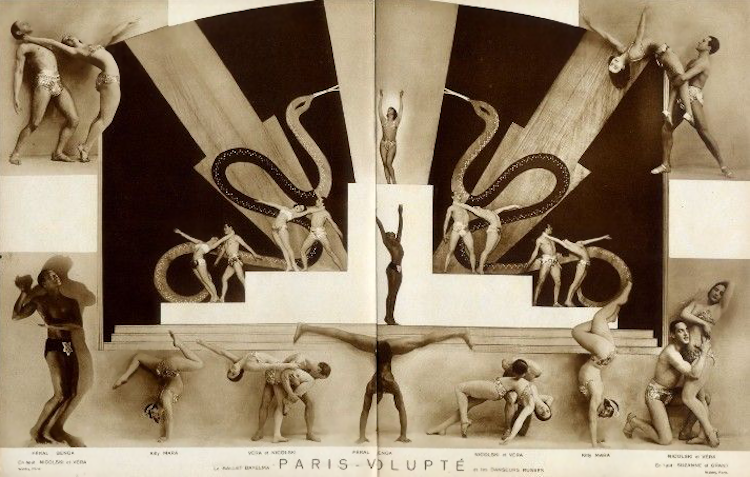

He performed with many stars – at some point his cabaret partner was the famous American-born Mexican dancer, the ‘Josephine Baker of Spain’, singer and actress Myrtle Watkins. The shy and somewhat introverted Benga pandered to the fetishised persona of the wild African warrior that was propagated by his booking agents.

He soon was a sought-after gay icon, with queer photographers, artists and film-makers gagging for him to star in their productions and artworks. He was cast as the Black Angel in Jean Cocteau’s avant-garde film Le Sang D’un Poete (The Blood of a Poet) in 1932.

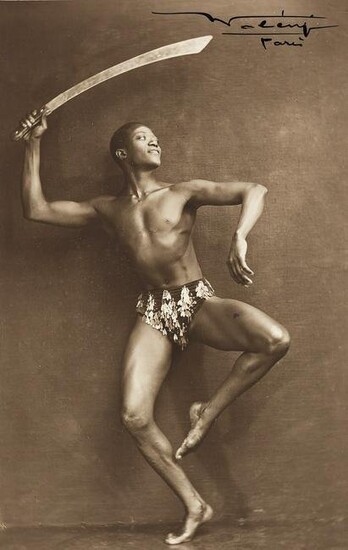

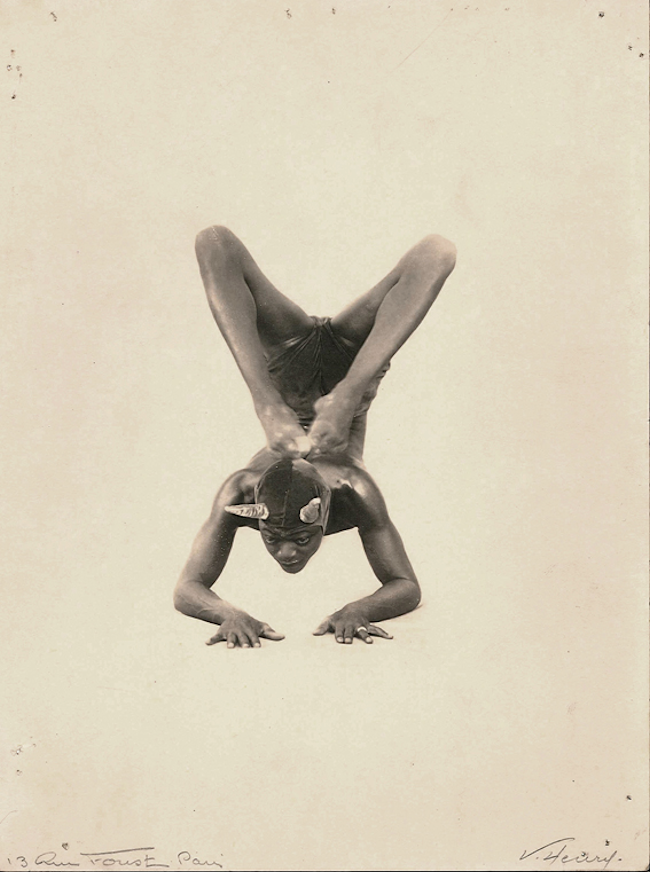

But the national obsession with Benga soon expanded into imagery, photographs, cabinet cards and postcards. He became a desirable model and muse to photographers like Polish photographer Lucien Walery, who was famous for his images of Josephine Baker: in an iconic photograph Benga held a machete below his hips, perfectly juxtaposing the vertical stance of his body. It was Walery’s image of the virile Feral Benga holding erect a machete overhead that inspired Harlem Renaissance artist Richmond Barthe to immortalize Benga in bronze in 1935 in a sculpture that stands two feet tall (the sculpture sold in 2020 for half a million dollars). Ever since much fuss has been made by art historians over the underlying psychoanalytical elements of the sculpture: the machete and phallic symbolism, the case for potential castration and the general erotic charge of the piece.

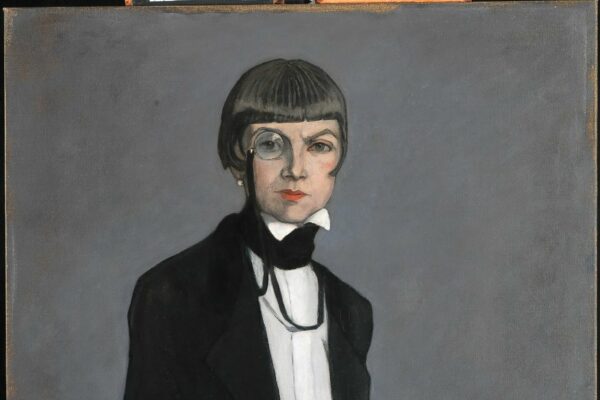

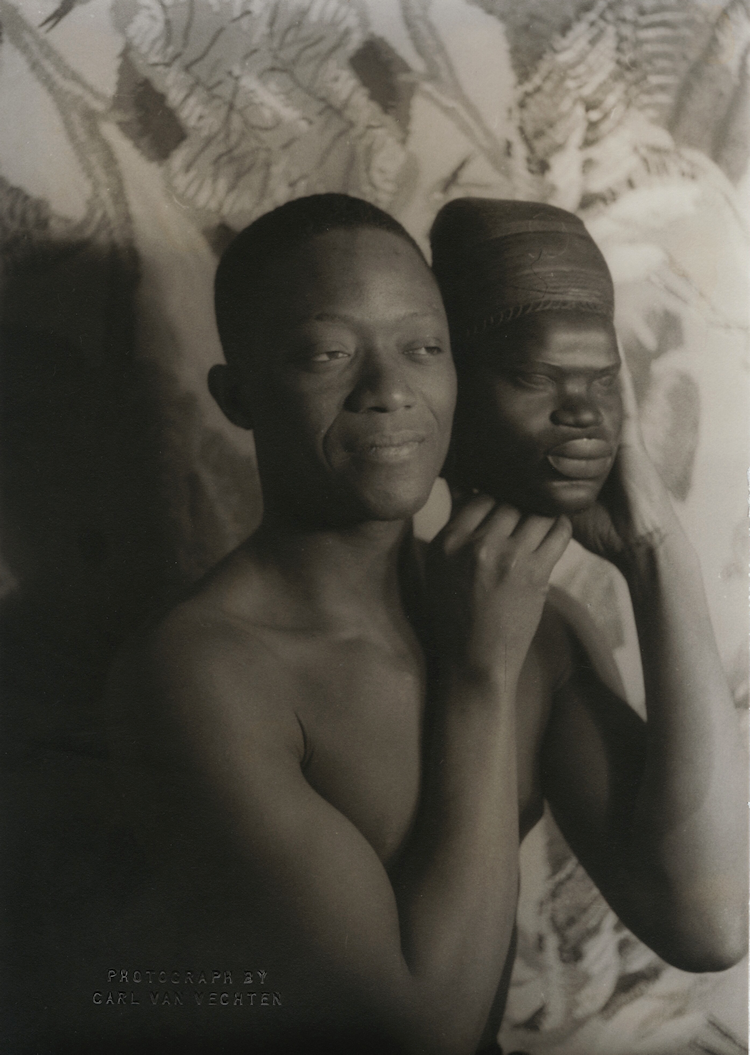

During this period, Benga was also the subject of African-American artist and art historian James Amos Porter’s oil on canvas portrait. He chose to clad Benga in an army uniform for a rather stoic painting entitled Soldat Senegalese. Writer Carl Van Vechten (who was Getrude Stein’s literary executor) photographed Benga clasping white lilies against his nude chest, as well as holding props like bongo drums, an African face mask, fruit and a cigarette – sometimes shirtless and sometimes in the nude. Emerging as an African muse of modernists, other artists who wanted a piece of the magnificent Benga were homoerotic photographer, George Platt Lynes, and Russian surrealist painter Pavel Tchelichew (his painting of Benga, Deposition, was owned by the co-founder of the New York City Ballet, Lincoln Kirstein).

Maintaining a presence on both side of the Atlantic, Benga continued to be a gay celebrity in Manhattan, all the while moving in the circles of the Harlem Renaissance. During this time he had many relationships and affairs, amongst these, one with Scottish-born novelist Kenneth Macpherson. Before the war in the 1940s, François Benga owned his own small bar and had lived in his apartment close to the Champs Élysées. The Nazi occupation of Paris with its racial and gay intolerance forced him to keep a low profile – although he did manage to both perform and choreograph dance in the ‘Tam Tam’ ballet at the Olympia Theatre.

Thereafter, Benga escaped to the countryside, where living rough destroyed him both mentally and physically; he didn’t return to Paris for four years. After the war, he opened a nightclub called La Rose Rouge at 53 Rue de la Harpe, in Paris’ Latin Quarter, showcasing African students as performers. This may have been the closest he came to fulfilling a dream of bringing some West African magic to France. Unfortunately, the club suffered from financial issues and was closed in 1956.

Benga was never as famous as some of his counterparts, like Josephine Baker for example. Reason for this may be that whereas female objectification of the body was not unusual in the 1930s, audiences didn’t know how to react to male objectification as deliberately flaunted by Benga on stage. Benga’s multifaceted character – being Black, African, gay, a muse, a performer and an artist – wasn’t easy to classify and categorise, and he tended to be treated as a type or caricature. For example, a classical piece he choreographed at the Theatre des Champs-Elysees (1933), was lambasted as “not African enough”.

Anthropologist and Benga’s romantic partner in the 1930s, Geoffrey Gorer, provided perhaps one of the best written sources on Benga in a book he wrote after a trip that he and François made to Africa to study tribal dance, Africa Dances: A Book About West African Negroes (1935). We can only deduce what we see from the pictures, sculptures and the odd bits of writing that Benga was proud to be a gay person, while also shy and introverted, and that he never managed to properly capitalise on the various ventures he was involved in, or indeed the very subject of.

According to Gorer, François was forever battling to keep the wolf from the door and maintain his lifestyle. Gorer wrote, “Actually he was very shy, much distressed by the fact that because he was a negro and a dancer everybody considered that they had a right, if not a duty, to make sexual advances to him.” However, it seems he had a reasonably lavish lifestyle up until WW2 – a plush apartment near the Champs Elysées, a custom-built convertible and a pack of poodles. When Gorer added a new preface to his book in 1962, it became clear that Benga was trapped at the onset of WW2 by Nazi occupation – French-speaking Africans were not tolerated – and spent four years stowed away in the countryside, where his physical and mental health withered. The last time Gorer saw Benga was in 1951.

François “Féral” Benga returned to his native Senegal a year before his death. Family pressure made him marry a cousin and he even fathered a son, but he returned to his beloved Paris, where he died in 1957 (or thereabouts) and was buried at the Saint-Denis cemetery in Châtearoux.