If you ever wondered whether the “Années Folles” really were ‘that crazy’ – we’re here to confirm that it was. Drunkenness, debauchery, drama and nudes, the bal des Quat’z’Arts (four arts ball) had it all; it’s little wonder then, that from its inception at the turn of the century, an invitation rapidly became the hottest ticket of the Paris season. Things got really wild by the 1920s as you’ll see in the early 20th century photographs, but before you proceed, there is plenty of imagery here that hasn’t aged well, featuring nudity and cultural appropriation (we’ve tried to edit where possible). In fact, there was very little about this bacchanalian ball that would fly today. You’ve been warned.

The bal des Quat’z Arts was an annual ball born in the Belle Epoque, organised by the students of Paris’s École des Beaux-Arts, a school dedicated to the four tenets of fine art; painting, sculpture, architecture and engraving. It was the brainchild of architect, and at that time student, Charles Cravio (known as Gargouillot) who apparently came up with the idea during dinner at a restaurant on Paris’ bohemian Left Bank. The idea was taken up and organised by Henri Guillaume, professor of architecture at the school, alongside a committee of students, and the first ball took place in the Elysée Monmartre on April 23rd 1892.

By all accounts the ball was an instant success, so by its second year, receipt of a personal invitation (the only way to get admitted) was akin to finding a Wonka Golden Ticket. However, even this coveted billet d’or was no guarantee to avoiding disappointment, as entry could still be refused at the door if ones costume was found lacking … in drama.

The second ball, held on February 9th 1893, took place at the legendary Moulin Rouge. A parade through the streets, with a half-naked Cleopatra at the centre surrounded by her scantily-clad servants, caused such a scandal that it resulted in a lawsuit. Described as an “act of extreme seriousness and unacceptable immodesty”, the organisers were sued by Réné Berenger, president of the League for the Defence of Morals. The models, including a famous redhead called Sarah Brown, known at the time as the ‘Queen of Bohemia’, were arrested, and after rumour spread that Miss Brown had taken her own life; several days of student riots followed in the Latin Quarter, resulting in the further death of one young man. The explanation later presented to the judge, stated that “the ball had been the occasion not of an orgy but of a tableau vivant [living painting] of three professional models”. Seemingly satisfied, the amused judge issued a symbolic fine.

by Henry Jules Charles Corneille de Groux 1902 (leightonfineart.com)

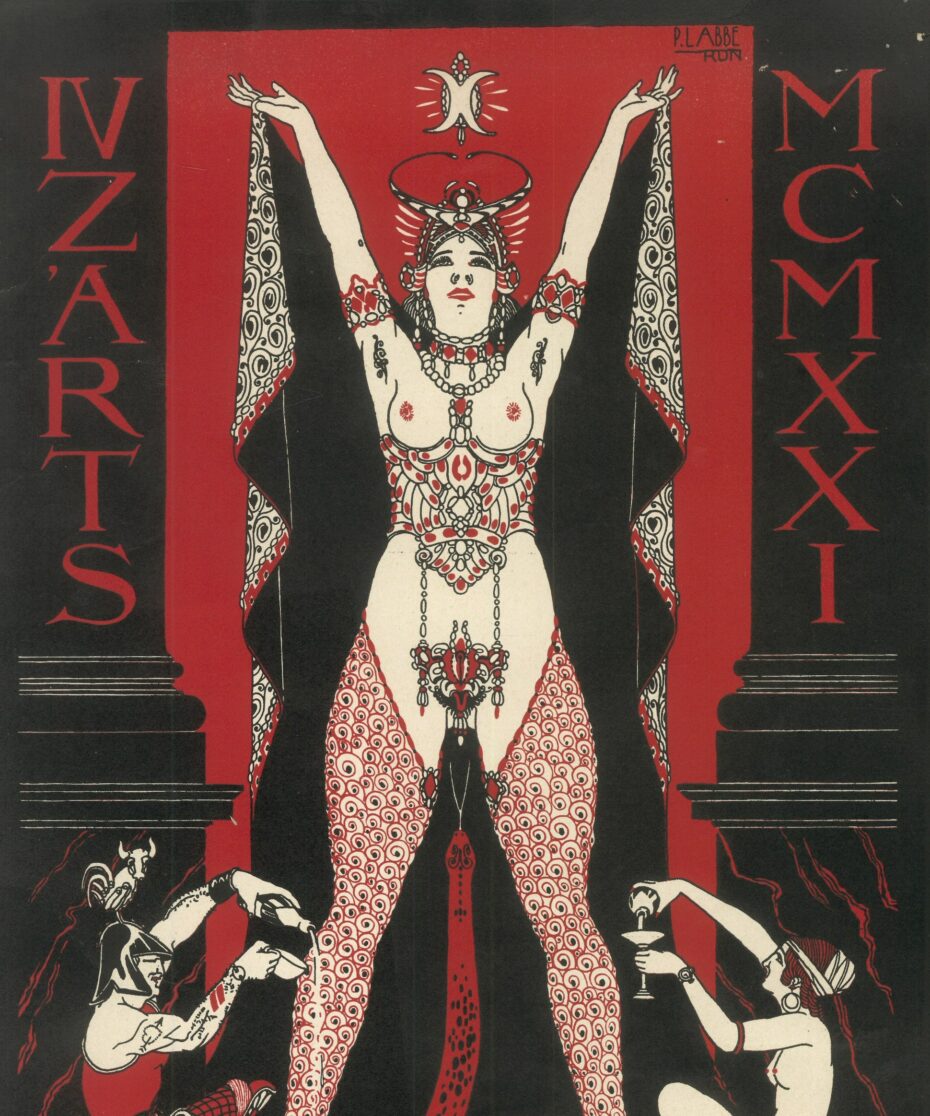

After this, the ball became an annual event, developing its own customs and rituals. The next seven were all held at the Moulin Rouge and from 1900, now organised by the ‘Comitards’ (a committee of students alongside writers and artists of Montmatre) it was given a fixed theme each year. Invitations, entry tickets, posters and a bronze were created for the occasion, based upon the chosen theme, showcasing the talents of the École des Beaux-Arts. Each was a work of art in itself, representing a history of artistic style from Art Nouveau through to modernism and the psychedelic designs of the sixties.

Themes, usually epic, included The Middle Ages, Ancient Egypt, The Sack of Rome, Carthage, Babylon, The Incas, Samurai and a particular favourite, the rather specific Entrance of Perseus into Athens. Invitations featured erotic imagery, just in case invitees were unaware of the direction the ball had taken.

Most early invitations bear the warning “Le nu est rigoureusement interdit,” (nudity is strictly prohibited) which was later modified to (translated): “The committee declines responsibility for any consequences that could result from the exhibition of the nude on the public highway”. Had the organisers resigned themselves to the inevitability of nudity (while attempting to avoid further lawsuits), or had their initial instructions been more dare than warning? You’ll find all the uncensored imagery we couldn’t bring ourselves to share here.

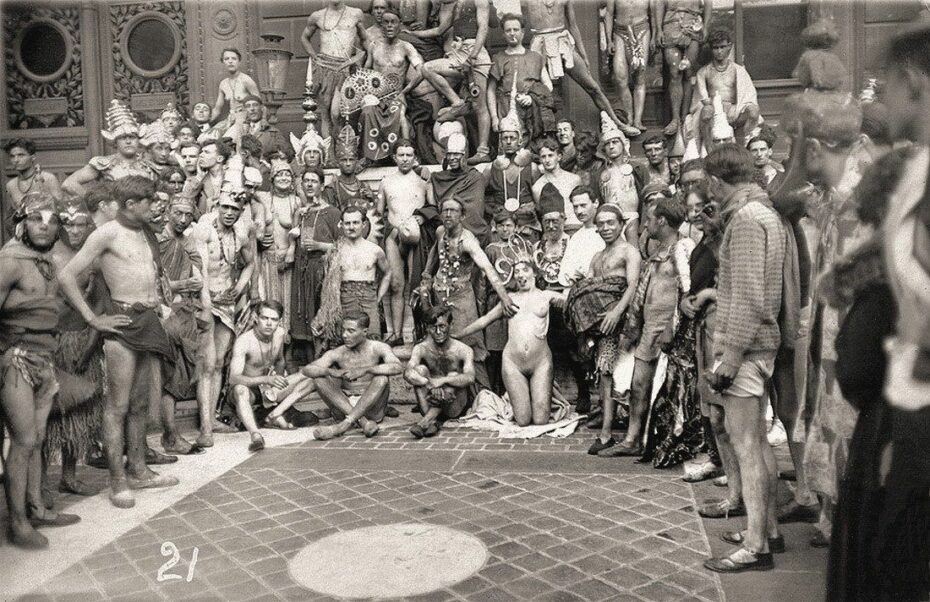

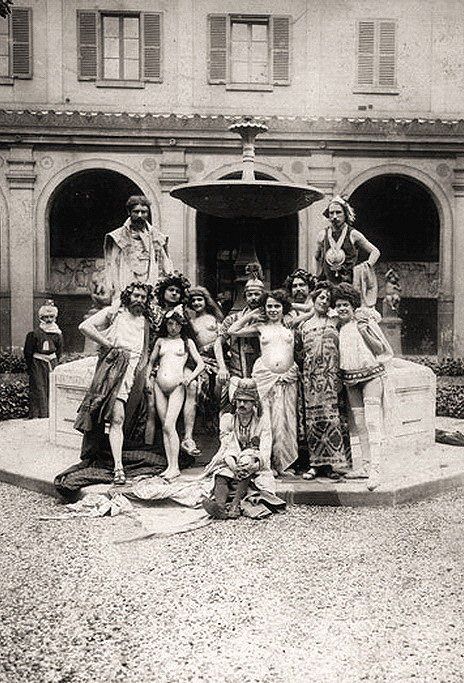

By now, the ball, having become an institution in its own right, followed a traditional itinerary which included two workshop competitions; best living painting and best parade. Each workshop at the school presented a display based on that year’s theme which was paraded on a float through the streets of Paris until it arrived at the venue where their stationary tableau vivent was also judged. In addition there were two individual competitions judged by a jury of artists for best helmet and best costume.

The evening proceeded with Bacchanalian aplomb; dinner and dancing, a parade of women astride their riders followed by a competition of nude (female) models. An abundance of drinking led to an abundance of naked flesh and what many described as an ‘orgy’ which went on until dawn when a lively folk dance known as a farandole rounded off the activities. A resounding chorus of “Long live the Quat’z’Arts” signalled that it was time to leave and a distinctly worse for wear procession of partygoers returned in groups via the Louvre, towards the Latin Quarter, where they disbanded as the rest of Paris’s day began.

It may have been difficult to swing an invitation to the ball but, luckily for us, those who did have left some graphic first hand accounts. In Bohemian Paris of Today, the American painter Edward Cucuel wrote:

“…we entered a dazzling fairy-land, a dream of rich color and reckless abandon. From gorgeous kings and queens to wild savages, all were there; courtiers in silk, naked gladiators, nymphs with paint for clothing,—all were there; and the air was heavy with the perfume of roses.”

He goes on to describe French painter Atelier Cormon’s “huge caravan of the prehistoric big-muscled men” in which “large skeletons of extinct animals, giant ferns, skins and stone implements were scattered about, while the students of Cormon’s atelier, almost naked, with bushy hair and clothed in skins, completed the picture.”

Cucuel enjoyed a long night of belly dancers and champagne (poured liberally over the dancers) which ended as the April dawn broke, whereby “the revellers returned through the streets of Paris, climbing lamp posts, turning over trash cans, and showing off their costumes to the citizens.”

The American expatriate E. Berry Wall, another eye witness living in Paris during Le Belle Epoque, wrote:

“It is a riot, a revival of paganism…it is also, in its way, a hymn to beauty, a living explosion of the senses and of the emotions.”

All accounts agree that both costumes and decorum were shed in direct proportion to the lateness of the hour and amount of alcohol consumed.

At its prime, the bal des Quat’z’Arts was the toast of the Paris season, prompting copycats and wannabes galore (one of the most notorious being the riotous Chelsea Arts Club Ball held on New Year’s Eve in the Royal Albert Hall, London, which ran until 1958). Excluding the years of the First and Second World Wars, the event continued until 1967 when the scandalous theme of the Tour de Neslé affair was chosen, but a venue was never found so it was cancelled. In 1968, student strikes led to the separation of the architecture department from the school – four arts no longer – and no further balls took place. In 2012, there was supposedly some talk of a relaunch but it was never pursued, so the ball still awaits somebody with the creativity, means and chutzpah to take it on. What would today’s Quat’z’Arts ball look like? The cultural appropriation part has mercifully had its day, so is there still a place for such high jinx?