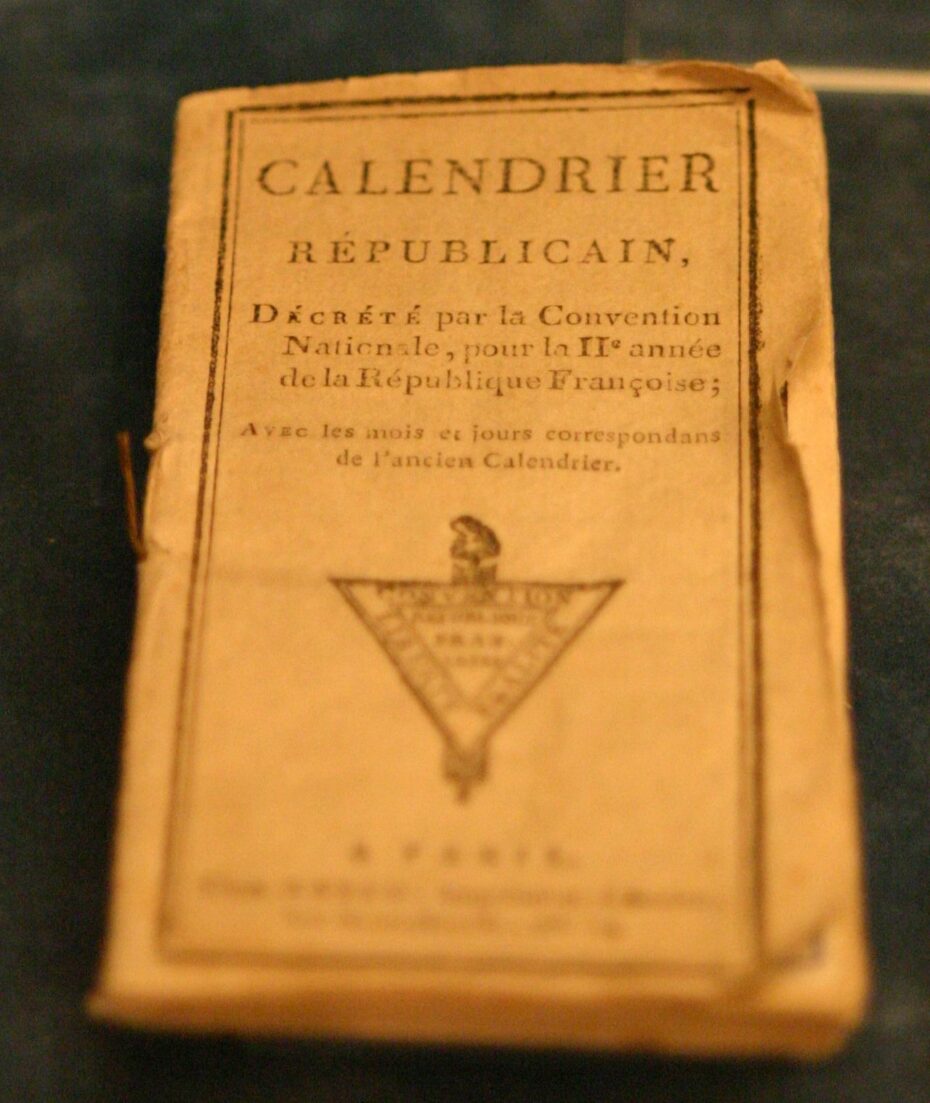

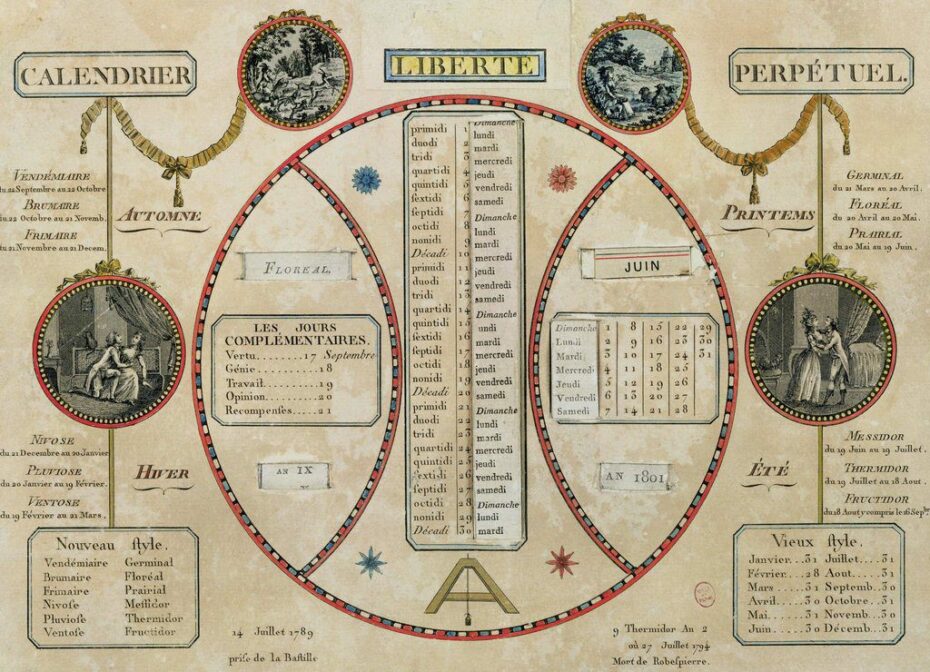

It’s the Year 232, cccording to the French Republican Calendar. If a wine’s vintage is decided by the year the grapes were harvested, wouldn’t it be fitting for France to celebrate the New Year at harvest time? At the turn of the 19th century, that’s just what France did. With the rise of the First Republic in the wake of the French Revolution, France was free of a monarchy for the first time, meaning the new government had an unprecedented opportunity to mold an entirely new society. The birth of Jesus defined Year 1 during the Ancien (old) Regime, but the birth of the new Republic called for a fresh start, and a new Year 1. France would be a nation of the Enlightenment – old Pope Gregory’s calendar and its saint days be damned. The autumn equinox (usually September 22 or 23), would become France’s (new) New Year’s Day.

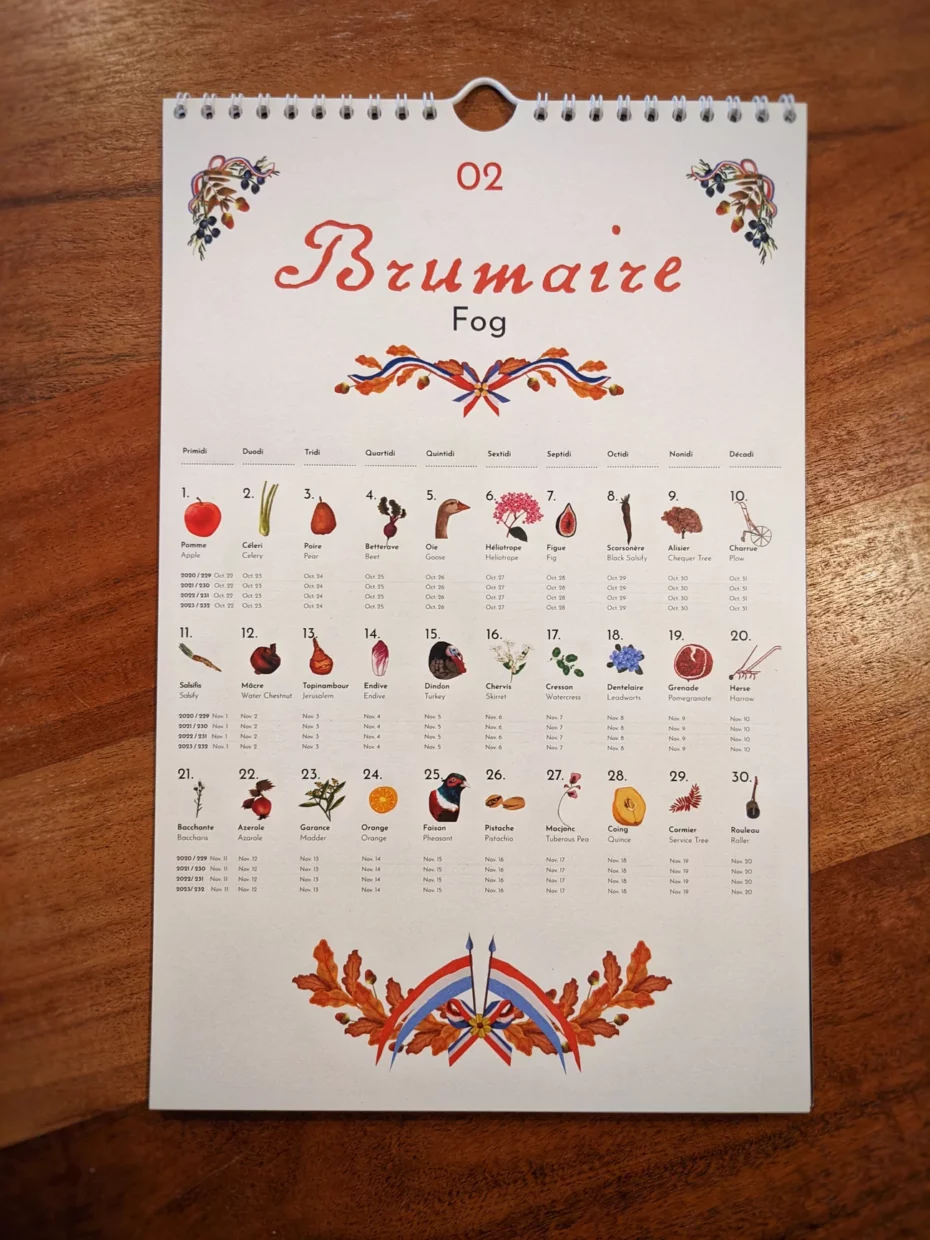

The first month of this new year would be called Vendémiaire, the Occitan word for “grape harvest.” Poet/playwright/politician Fabre d’Églantine came up with that (he was from Occitan-speaking Carcassonne.) Églantine named all the new months to reflect France’s climate and agrarian cycle. He was part of a government sponsored commission of savants (“wise ones”) – mathematicians, astronomers, geographers, and horticulturalists, dedicated to reinventing how France kept time.

Another government-appointed commission had a parallel undertaking: To give France a standard unit of weights and measures. Centuries of feudalism had crumbled Roman standardization into about 800 regional measurement systems across the country. According to the National Geographic, “In early 18th-century Bordeaux, a unit of land was defined by how far a man’s voice carried.” But this wouldn’t do for an Enlightened nation. Under the leadership of philosopher and mathematician the Marquis de Condorcet, the commission was hard at work developing the metric system.

In keeping with the metric commission’s effort, the calendar commission fixated on multiples of 10. They retained 12 months in a year, but broke each month into three ten-day weeks. This was elegant on paper, with every month bearing 30 days. The downside of the ten-day week was that workers didn’t get a day off until the tenth day! Gone was the religious basis to rest on the seventh day. Relatedly, and keeping in mind that the French revolutionaries and the Church were not exactly on good terms, Christmas became an anti-saint day in honor of Isaac Newton, conveniently born on that day.

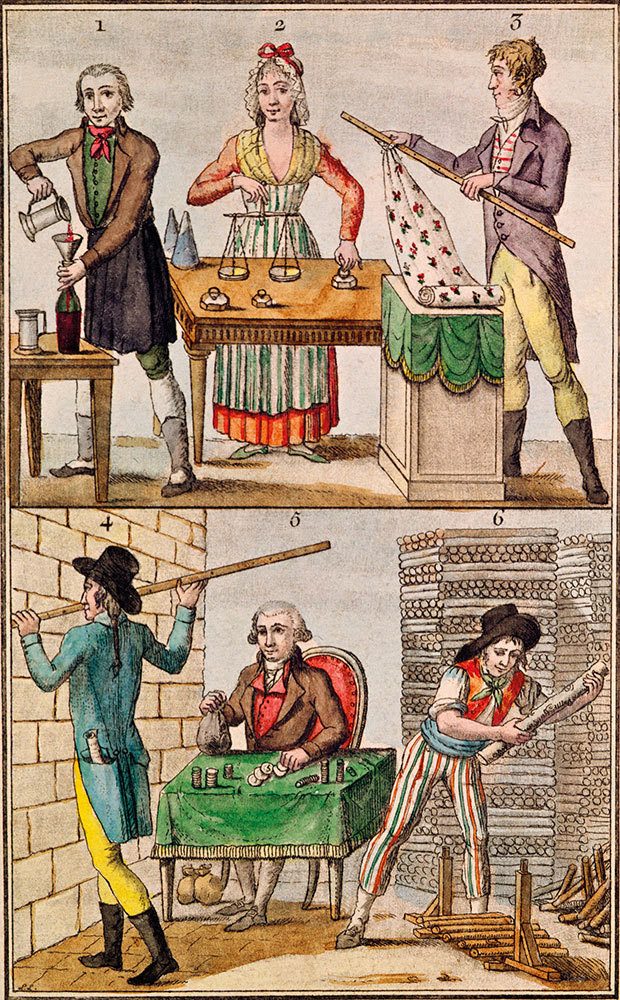

The devotion to “reason” was clearly more theoretical than practical, and the ten-day week seemed to contradict the Republic’s raison d’être of elevating the masses. In fact, the calendar’s structure was very much like that of Ancient Egypt, a slave-based civilization. The decimal calendar also had a scientific flaw: the earth took 5 or 6 more days each year to complete its orbit around the sun than the calendar accounted for. The commission passed these extras off as “complementary” days, a vacation at the end of the year, though it certainly didn’t make up for the loss of Sunday. Seemingly adding insult to injury, the complementary days were also called the Sansculottides, essentially “commoner days.” But of course, it was the working class, trouser-wearing sans-culottes (without the fashionable silk knee-breeches worn by nobility) who mounted the Revolution.

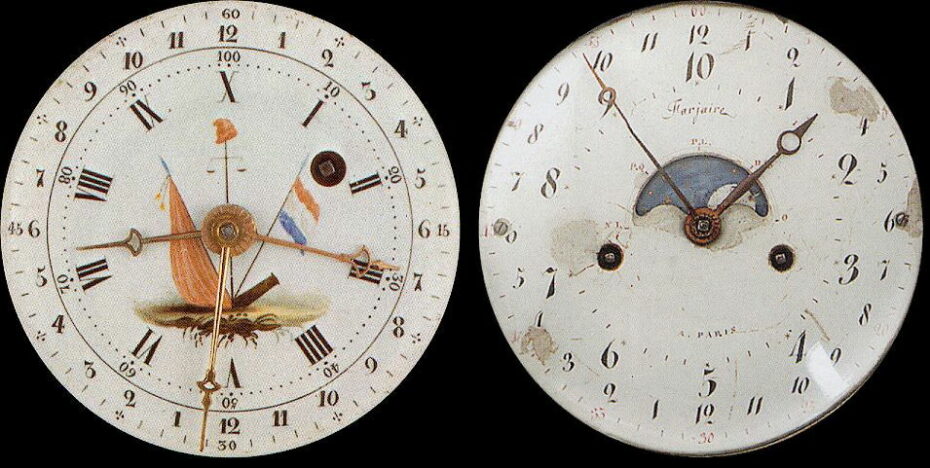

The wonks didn’t stop at decimalizing the calendar, they also decimalized the clock. The day was divided into just 10 hours – that’s 10 hours total, not 10 hours am and 10 hours pm. An hour consisted of 100 minutes, and a minute consisted of 100 seconds. Again, elegant in theory, tiresome in life. Clockmakers produced a bevy of new timepieces with both 12- and 10-hour dials as well as both Gregorian and Republican calendar dials to help people adjust. Several examples can be found at the newly restored Carnavalet Museum, the museum of the history of Paris.

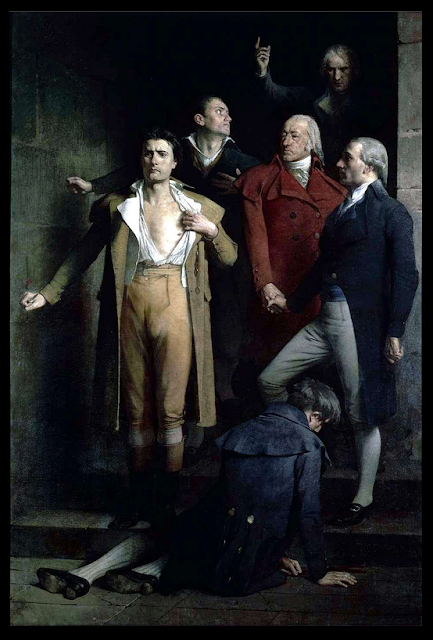

The French First Republic was like Project Runway: One day you’re in, and the next day you’re out. In March 1794, metric system champion the Marquis de Condorcet died in jail, and our month-naming friend Fabre d’Églantine met the guillotine. In July of that year, Maximilian Robespierre too met the guillotine, ending his “Reign of Terror” and inciting a new period known as the Thermidorian Reaction, named for d’Églantine’s hot month of Thermidor. But in June 1795, death came for the chairman of the calendar committee, mathematician-turned-politician Charles-Gilbert Romme. (Fun side note: Romme tutored Count Pavel Aleksandrovich Stroganoff, for whom beef stroganoff is named). A Thermidorian Reaction military committee sentenced Romme and five fellow Montagnard politicians to the guillotine. Shortly after sentencing, the six doomed men stabbed themselves with two concealed knives and a pair of scissors, an act of collective suicide. Romme and two of his comrades quickly perished. The other three went to the guillotine, though one was dead by the time he got there. The six men are known as the Martyrs of Prairial, referring to the month of their death.

But Romme’s calendar and decimal time remained in use until Emperor Napoleon I abolished them in 1806. Just as the National Convention government had conceived of a new calendar as a way to break with the Ancien Regime, Napoleon didn’t want his empire associated with the Revolution. However, he wasn’t interested in creating yet another calendar. He returned France to the Gregorian calendar and the 24-hour day.

The implication was that Napoleon’s reign was rightfully inevitable in the course of history. Getting back on schedule with the rest of Europe also made sense for a guy conquering the continent and the revolutionary Republican Calendar had actually been instituted across Belgium and Luxembourg, and made it to parts of Holland, Germany, Switzerland, Italy and Malta. No more, Napoleon said. He still had the metric system to deal with, which he described as “tormenting the people with trivia,” quotes National Geographic.

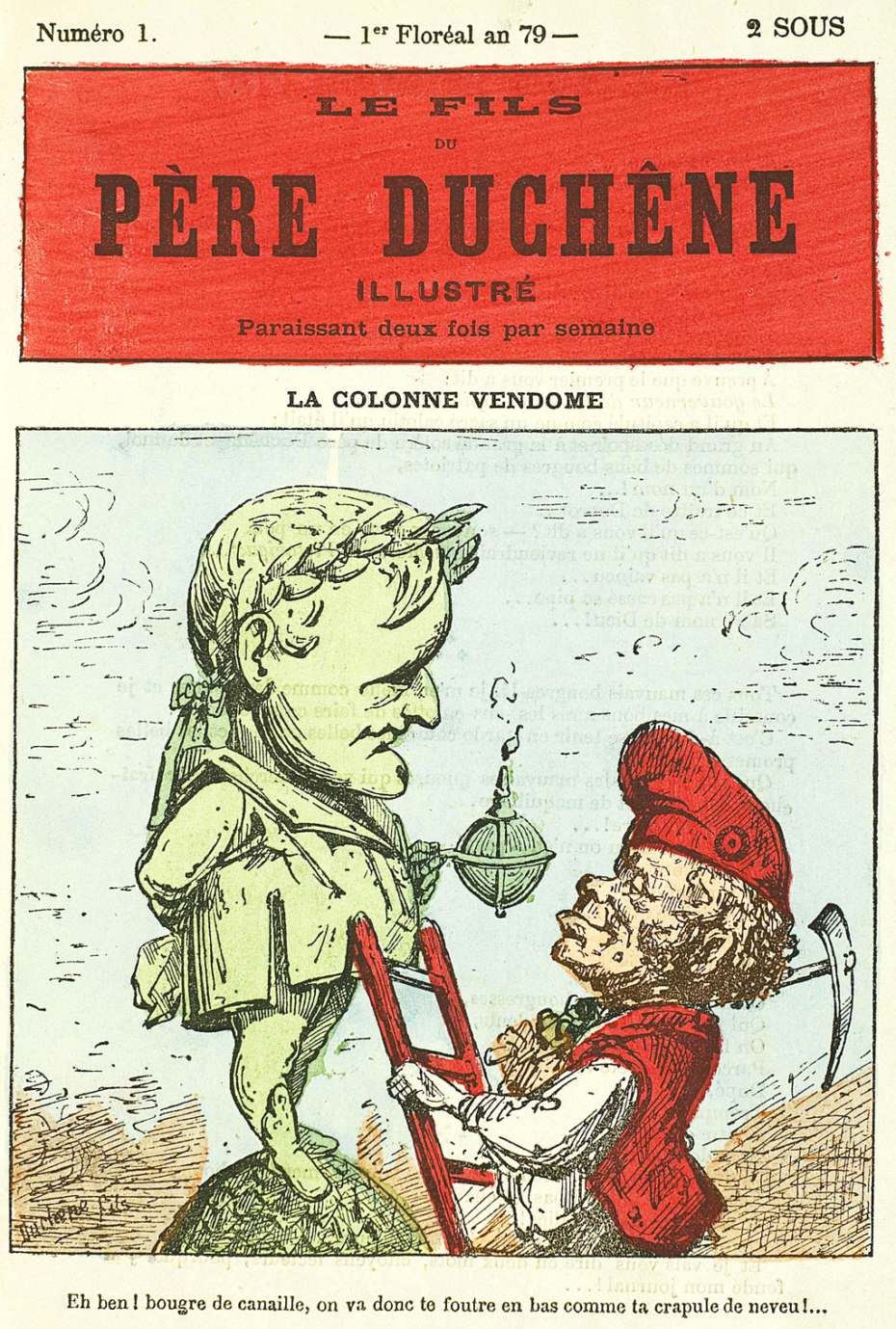

In March 1871, nearly 80 years after the birth of the First Republic and its calendar, there was another revolution, this time, proletariat rebels seized Paris and established a Democratic-Socialist government – the Paris Commune. For 18 days in May, the Paris Commune brought back the Republican Calendar, aligning themselves with the spirit of the Revolution. They didn’t last till June.

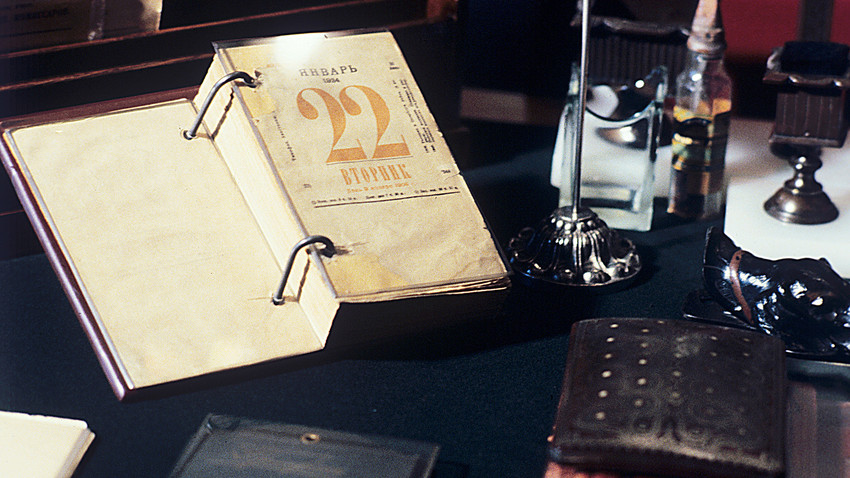

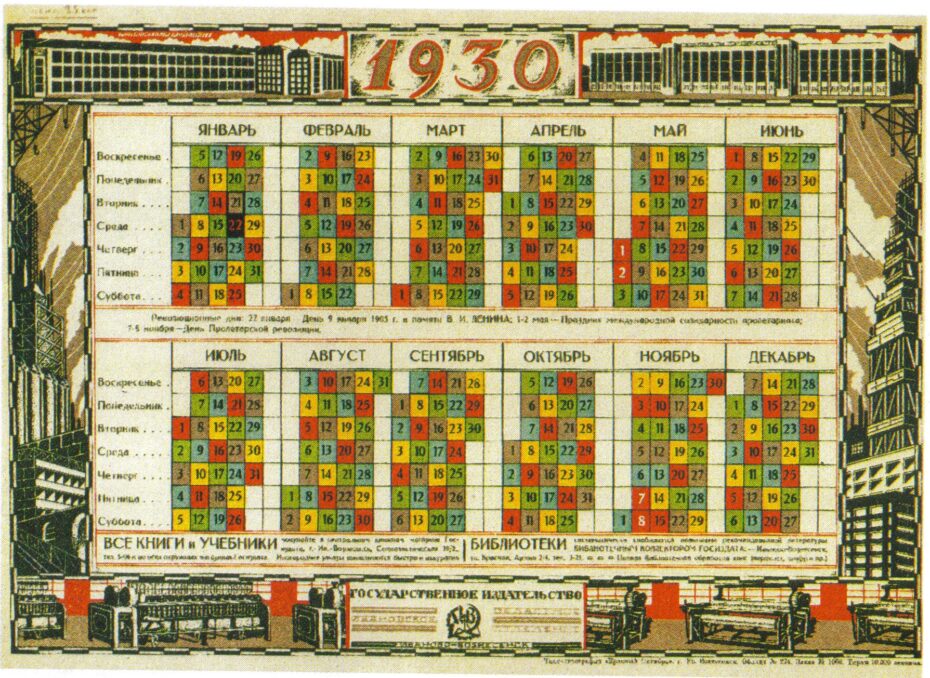

The Paris Commune was an inspiration to the Bolsheviks during the Russian Revolution. One might even say communism was born in Paris. In the Jacobin.com article “The Paris Commune Taught the Bolsheviks How to Win a Revolution,” Russian historian Andy Willimott states, “Lenin was so enthused by the Paris Commune that he danced in the snow the day the Bolshevik government had lasted longer than its French forebear.” Out of this enthusiasm, the Bolsheviks seem to have considered adopting the French Republican Calendar. They wanted to upgrade to some new calendar or other because Tsarist Russia had clung to the Julian calendar, dating to Julius Caesar (also see “How Humans Have Toyed with Time.”) By 1900, the Julian calendar was 13 days off! The Bolsheviks ultimately decided against the French Republican system, instead, asserting Soviet Russia’s modernity by joining Europe in the Gregorian system.

After the Paris Commune, the French Republican Calendar was never adopted again, but buildings from the First Republic can still be spotted with their odd dates. There also seems to be the occasional later tribute: a fountain in Octon, Hérault in the south of France, for instance, bears a plaque reading, “République Française 5 Ventôse an 109.” That is, February 24, 1901.

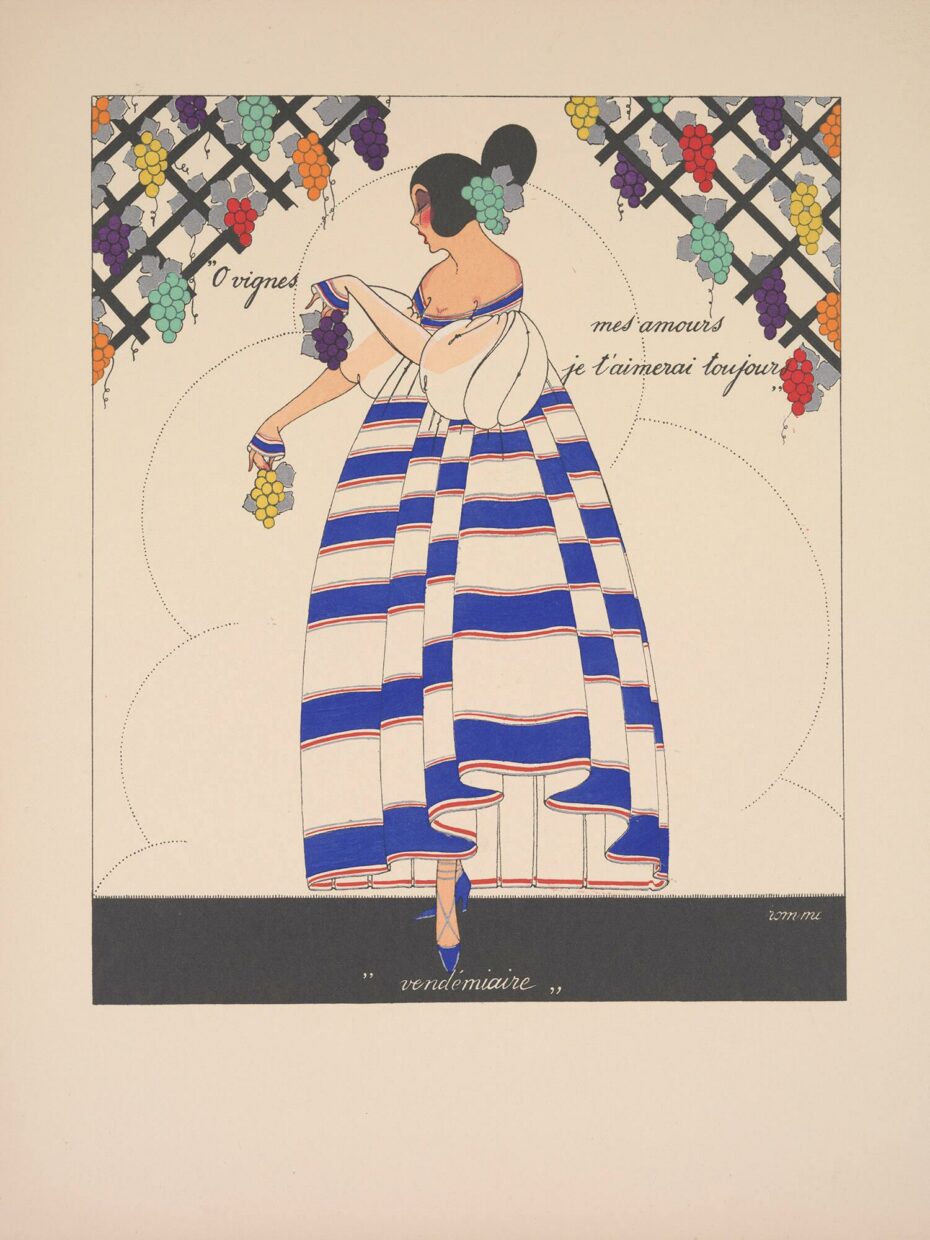

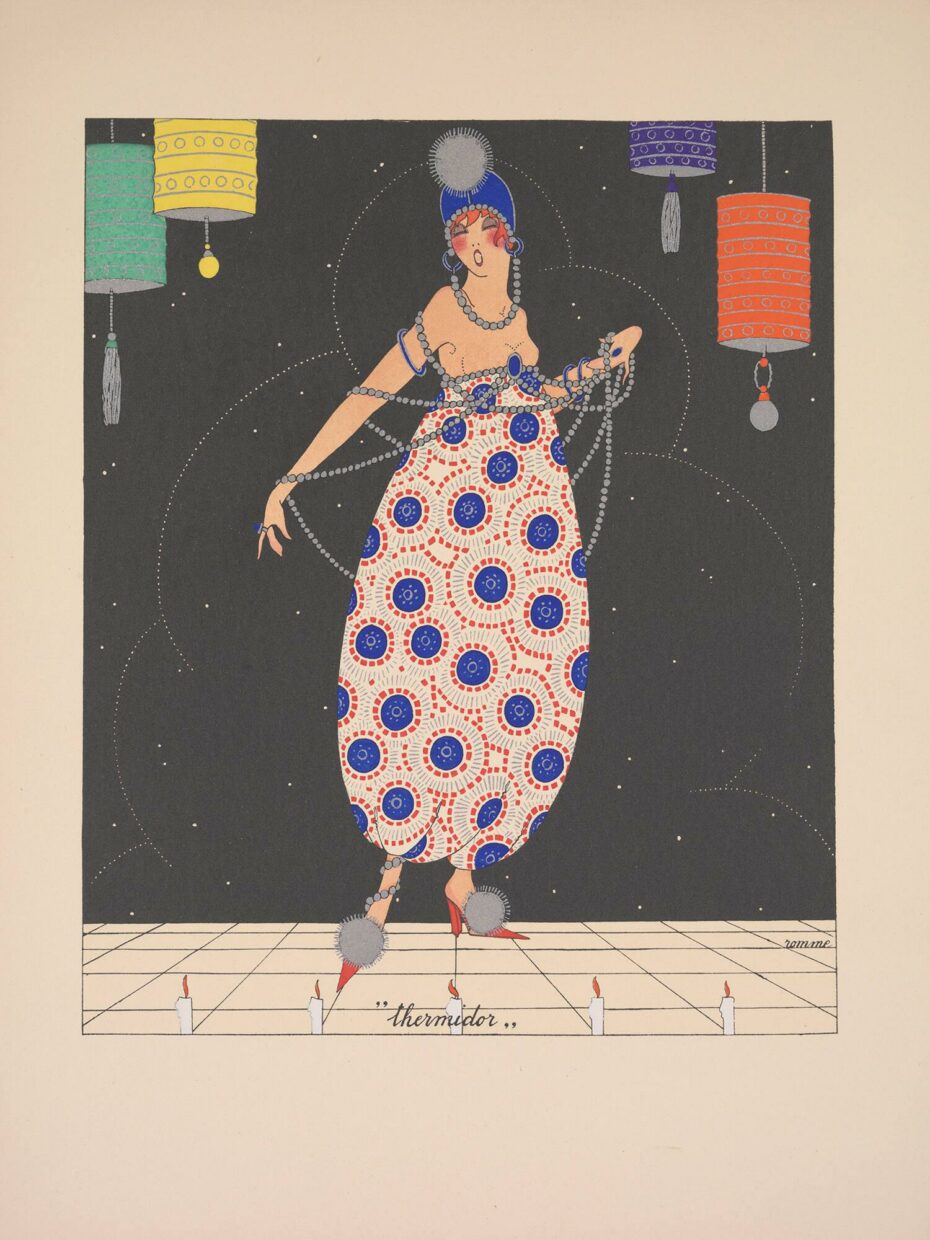

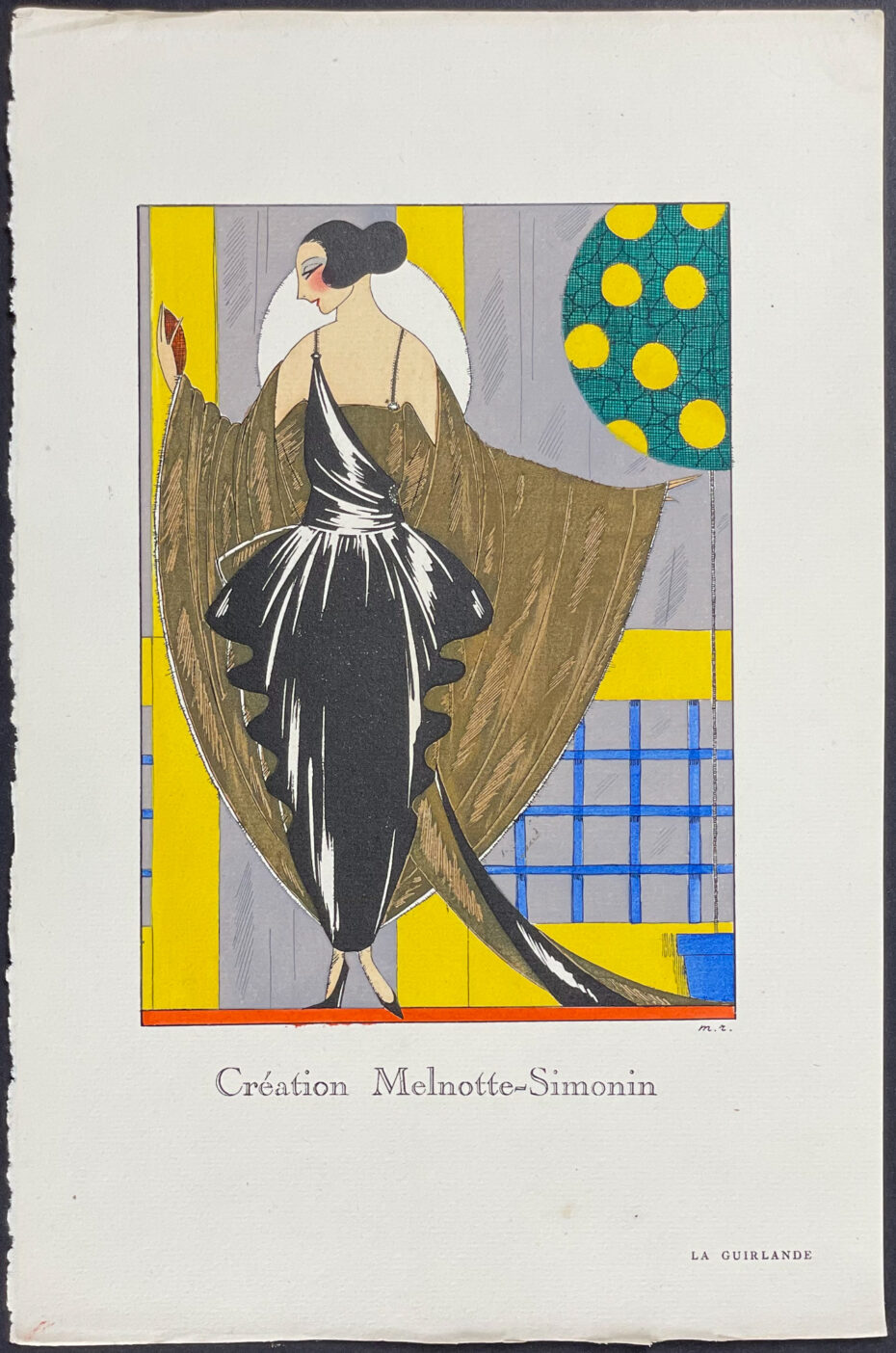

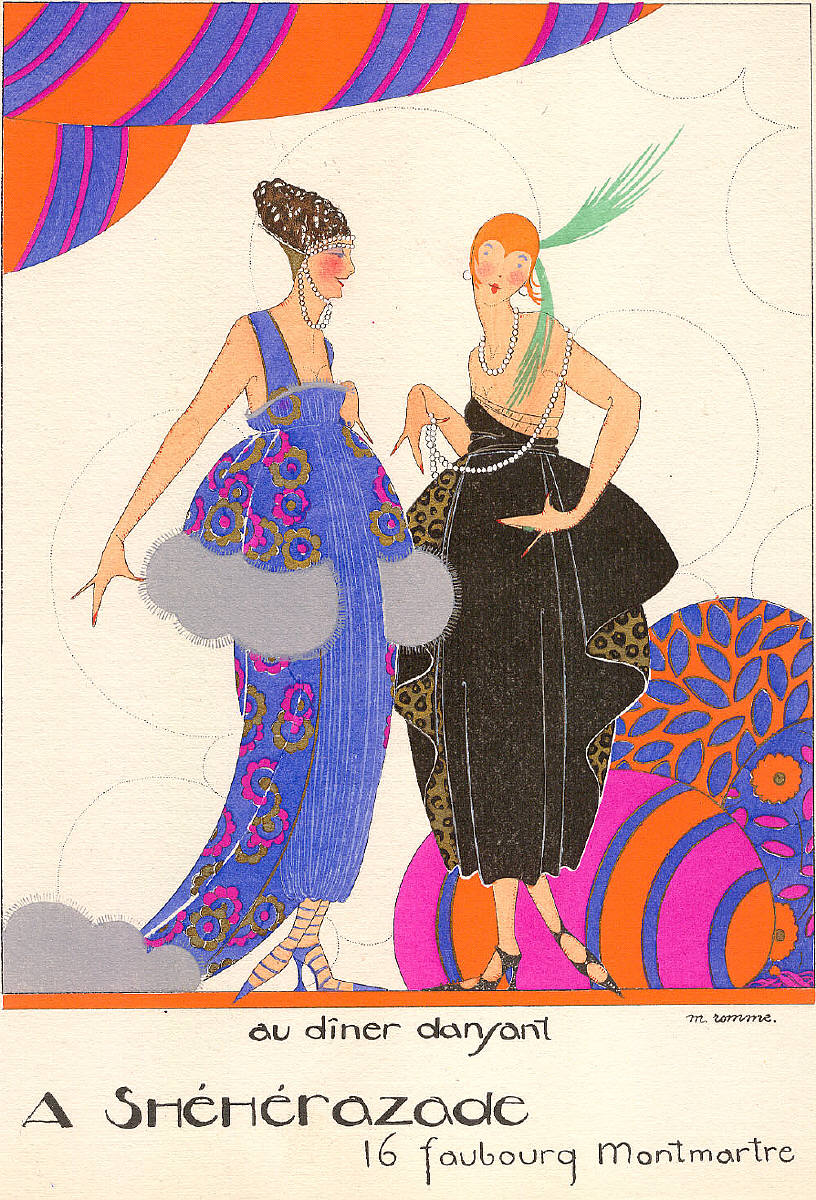

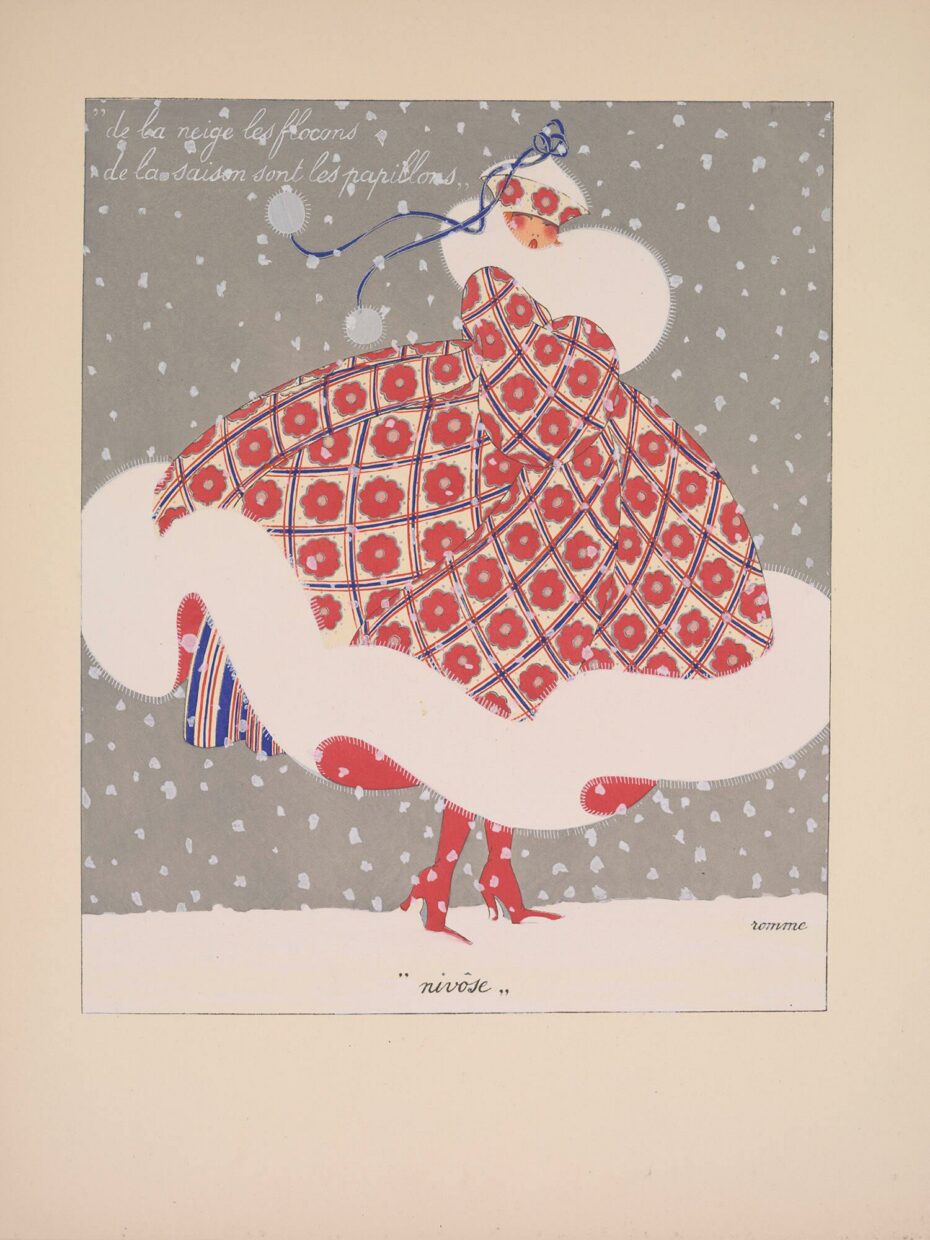

Another revival of the French Republican Calendar appears in Chéri Hérouard’s illustrations for La Vie Parisienne and Fantasio magazines during and shortly after World War I. Fashion illustrator Martha Romme made a set of striking pochoir (stencil) illustrations, The Twelve Months of the Year (1919), on the same theme, in the same era. She may have also created an earlier set, since entirely different iterations of the months of Pluviôse, Germinal, and Thermidor appear online, signed by Romme and dated 1917.

As with Hérouard’s illustrations, Romme rendered women in seasonal settings, titled with the corresponding Republican Calendar months. A subtext of French patriotism seems underscored by her characters’ dramatic outfits in the colors of the Tricolour flag. These prints beg the question: Was Martha Romme a descendent of calendar commission leader Charles-Gilbert Romme? Martha Romme’s work is all over Pinterest and her calendar girls have even been adapted to cross-stitch patterns on Etsy. But information about her is nowhere to be found.

Edition number 136 of Romme’s The Twelve Months of the Year is held by the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, which sells reproductions. When contacted for further info, the museum press office consulted the collections team and replied, “Unfortunately we do not have additional information on this item or the artist. As is noted in the Object Details on the collection item page, we know it was a gift from painter and photographer Mrs. Joshua Montgomery Sears, Jr. to Isabella Stewart Gardner in 1921.” Gardner and Sarah Choate Sears were both fabulously wealthy Bostonians who poured their money into collecting art. Gardner established and personally curated the eponymous museum devoted to her collection. As the press office mentions, Sears was an artist. Her watercolors won prizes at multiple international expositions and she exhibited in Paris and traveled through Europe with Mary Cassatt and Gertrude Stein. It’s easy to imagine the Boston Brahmin impulse-buying Martha Romme’s The Twelve Months of the Year from the publisher Sauvage at 370 Rue Saint-Honoré, or perhaps from one of the bouquinistes along the Seine near Notre-Dame.

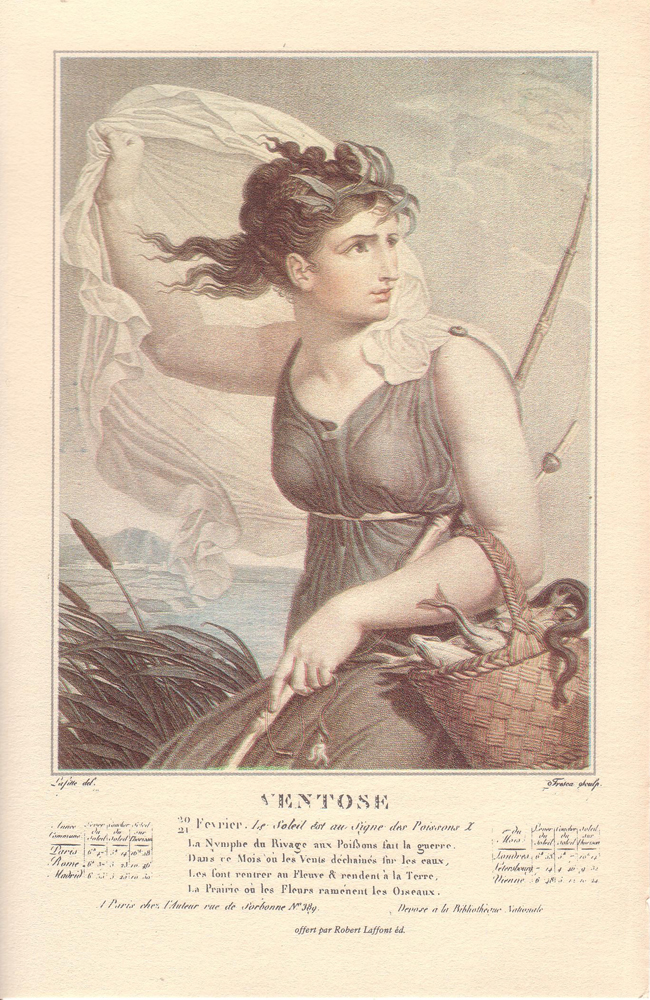

If the mysterious Martha Romme’s name seems more than a coincidence in connection with the French Republican Calendar, so too does her inclusion of poetic lines about the months. (Think “April showers bring May flowers.” Oddly, she includes such lines for most of the months, but not all.) These seasonal verses suggest she was familiar with a calendar-girl series actually dating to the First Republic which includes seasonal verses as well. Drawn by Louis Lafitte and engraved by Salvatore Tresca c. 1792-1794 (according to the Rijks Museum in Amsterdam, but dates vary) this is the series you’re guaranteed to see if you look up the Fench Republican Calendar today. Wikipedia uses Lafitte and Tresca’s prints to illustrate the months. Yet we can only wonder how Romme knew of them.

The verses in Lafitte and Tresca’s series are also noteworthy because they’re full of nymphs and naiads and references to the zodiac. Windy “Ventôse,” for one, refers to “The Nymph of the Pisces Shore” making war between water and air. Further, each page states the month’s astrological sign. All this completely undermines the Enlightenment purposes of the new calendar system.

That said, under poet Fabre d’Églantine, the calendar commission created a layer to their work that was as much a non-proletarian amusement as astrology. In place of saint days, every fifth day (quintidi) honored a common animal, every tenth day (decadi) honored a farm tool (on the day of rest, ironically), and the other days honored seasonal plants. The autumn equinox was naturally Grape day, for example, and the spring equinox the day of the Primrose. Nivôse, the month bridging December and January when plants are dormant, received minerals instead. January 1 was Clay day, for instance. The sentimental system smacks of a poet in Paris who’d never held a shovel, the hyper-specificity akin to the Victorian Language of Flowers.

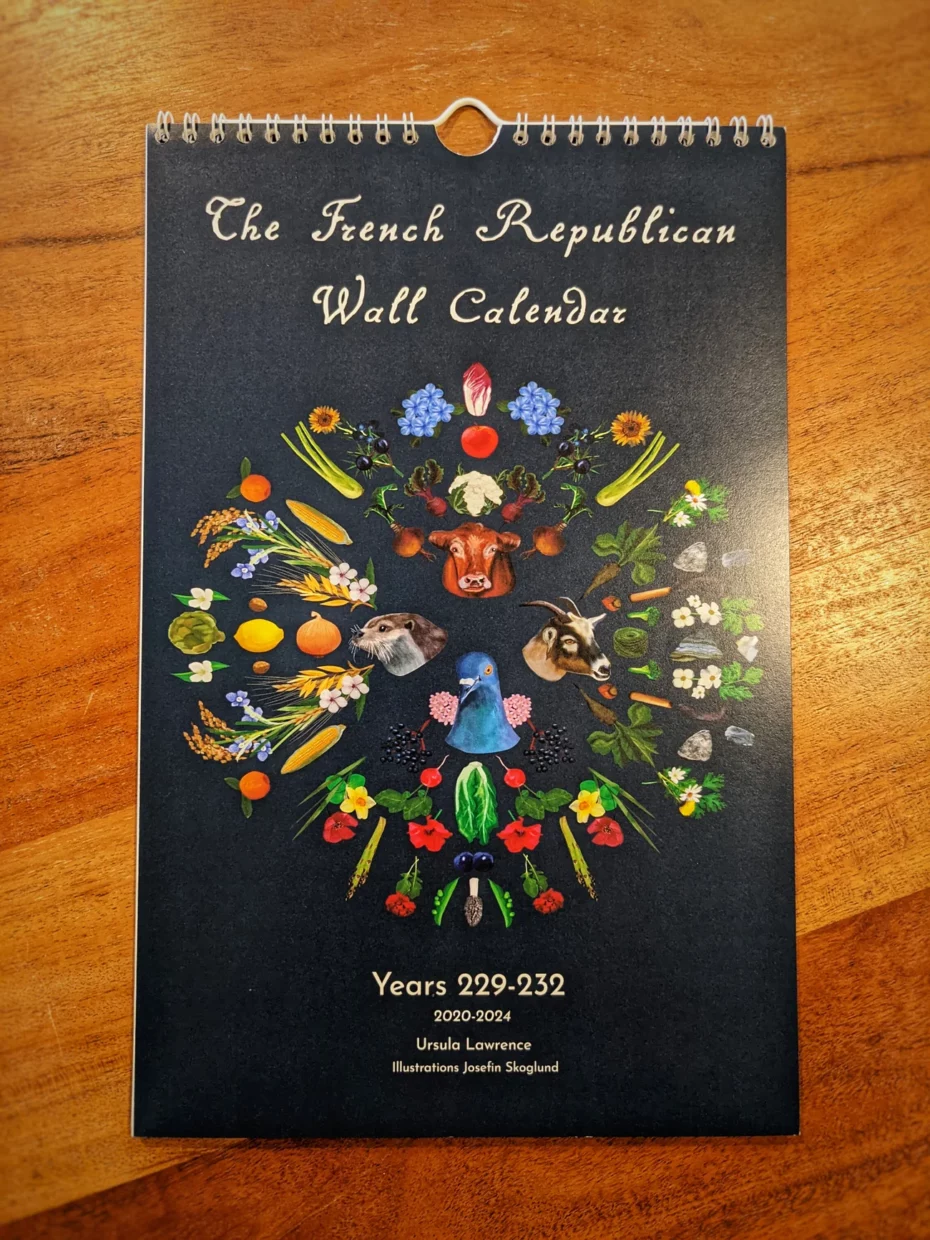

In 2015, Karate Fight Publishing released a charming wall calendar illustrating this daily system, and it sold out. Its American author Ursula Lawrence writes, “it is precisely the specificity and breadth of the items that, I believe, makes this calendar so unique and evocative.” Lawrence affirms its allure in the introduction to the 2020-2024 edition, sharing, “The first volume now hangs in homes in more than 20 countries. It is most popular in Britain (what is it with you people and the French?) but loyal revolutionary citoyens” (citizens) “exist in the US, Canada, France, Norway, Russia, Japan, Brazil, Mexico and so on. Vive la révolution, indeed.”

The French Republican Calendar was only officially in use for 13 years, but it has been revived or at least referenced again and again for its idealism, patriotism, poeticism, and whimsy. Émile Zola named his 1885 miner’s strike novel Germinal. An 1891 dramatic play, Thermidor, about the Thermidorian Reaction, inspired Auguste Escoffier to whip up the decadent dish of Lobster Thermidor. And since 1992, the French Navy has boasted a fleet of surveillance frigates, the Floréal class, each named for a Republican Calendar month. Where will this calendar pop up next?

Written by Allison Strauss