Cast your eye over the creations of Jacques Griffe, and one can’t help but wonder why a designer so acutely gifted doesn’t also boast a couture legacy similar to that of many of his contemporaries. Griffe closed his business in the late 1960s despite earning his reputation as one of the great French couturiers of the mid-20th Century. We find shockingly little written about the life of this fashion genius, however. The more we look for words, stories and anecdotes, the more our thirsty web searches are greeted by tiny snippets of hearsay and a few sparse details about the legend that was French design maestro. What we do find in place of his story, is plenty to look at; reams of images of Griffe’s haute couture creations have been meticulously documented over the decades. The most exquisite ballgowns, the cheekiest little tweed suits and most joyous beach dresses are alive and well in the cloud (and some in the flesh in the wardrobes of many collectors), each telling its own story on behalf of a man that in truth should’ve been as famous as his contemporaries Madeleine Vionnet, Elsa Schiaparelli and Christian Dior.

It was an apprenticeship under a local tailor near his birthplace outside Carcassonne at the age of 16 in 1925, encouraged by his enthusiastic mother, that saw Griffe set off on a lifetime of bespoke fashion. The House of Mirra in Toulouse followed as training ground in honing the young Jacques’ skillset, but it was perhaps the inevitable move to fashion capital Paris in 1935 that shaped and fine-tuned his style in the most impactful way. He got the job as pattern cutter for arguably the most visionary European couturier of the thirties, the inimitable Madeleine Vionnet (1876 – 1975).

Vionnet revolutionized a style that changed the shape of women’s fashion forever with her avant-garde bias-cuts (a cut that doesn’t follow the straight-of-grain of the fabric, but instead places a pattern at a 45 degree angle on cloth, allowing the fabric a natural stretch). This technique with its built-in elasticity allowed her gowns to snugly hug the curves of the female body, and made fabric draping into an even more pliable artform. Flanking the doyenne of drapery, for three years Jacques Griffe soaked up all the subtle tricks of the trade and squirrelled them away for the day he was going to debut his own offerings.

That day came in 1941 when Jacques Griffe opened his eponymously-named haute couture salon in rue Gaillon. By this time, the second world war had come and gone, he had served in the war and had spent 18 months in a prison camp. By the late 1940s, celebrities were queueing at the House of Jacques Griffe and the likes of Ingrid Bergman and Josephine Baker were amongst those sporting his haute couture creations. In 1948, he launched a more affordable pret-a-porter range named ‘Jacques Griffe Evolution’, and created fragrances ‘Enthusiasm’ and ‘Doodle’ to accompany his clothing lines.

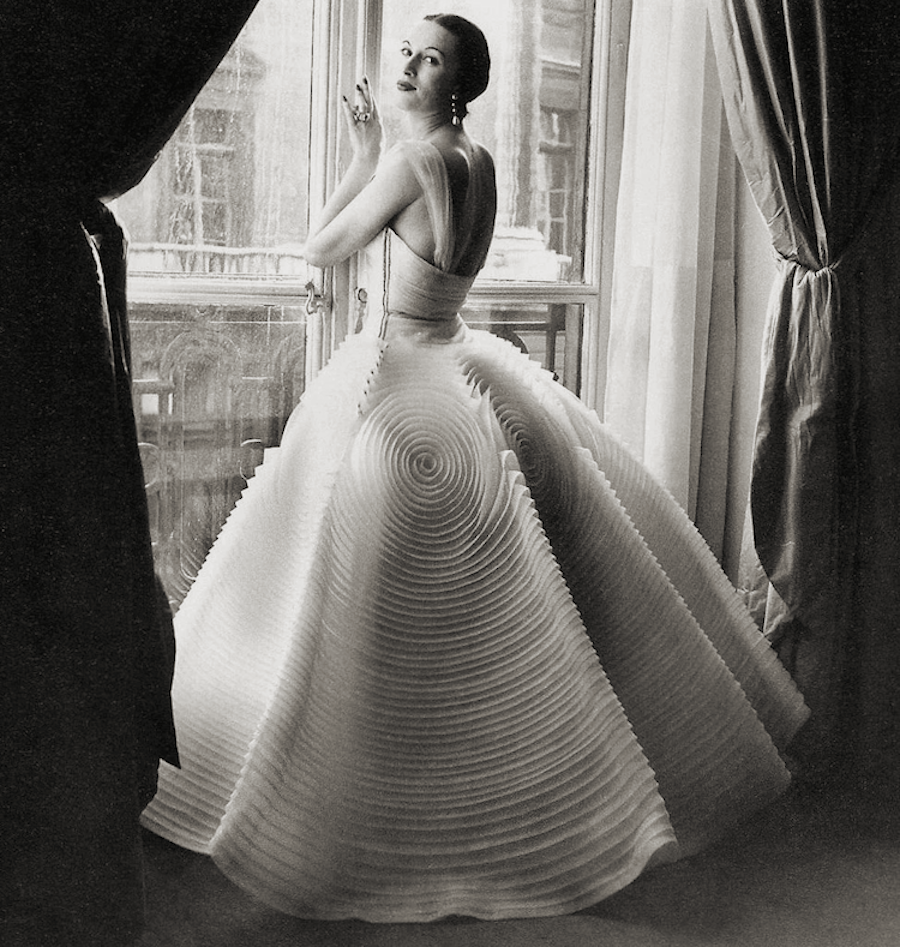

Jacques Griffe was a gifted one-stop shop creative: he would dream up designs, sketch them artfully, cut his patterns with acute technical prowess, drape fabric like a magician and also sew up his creations. Of all of these skills, it’s perhaps his ingenious ability to drape cloth that we should remember him for best. No doubt it helped that his schooling was with the queen of drapery, Madeleine Vionnet. It was the uncanny ability to marry the properties of a given fabric to a particular design that let him create his most memorable pieces. He was masterful in manipulating fine fabrics like chiffon, voile and lamé. Using a mannequin gifted to him by Vionnet, he’d effortlessly ply fabric into folds and artful drapes, with his creations being wearable, tactile works of art rather than just fashion.

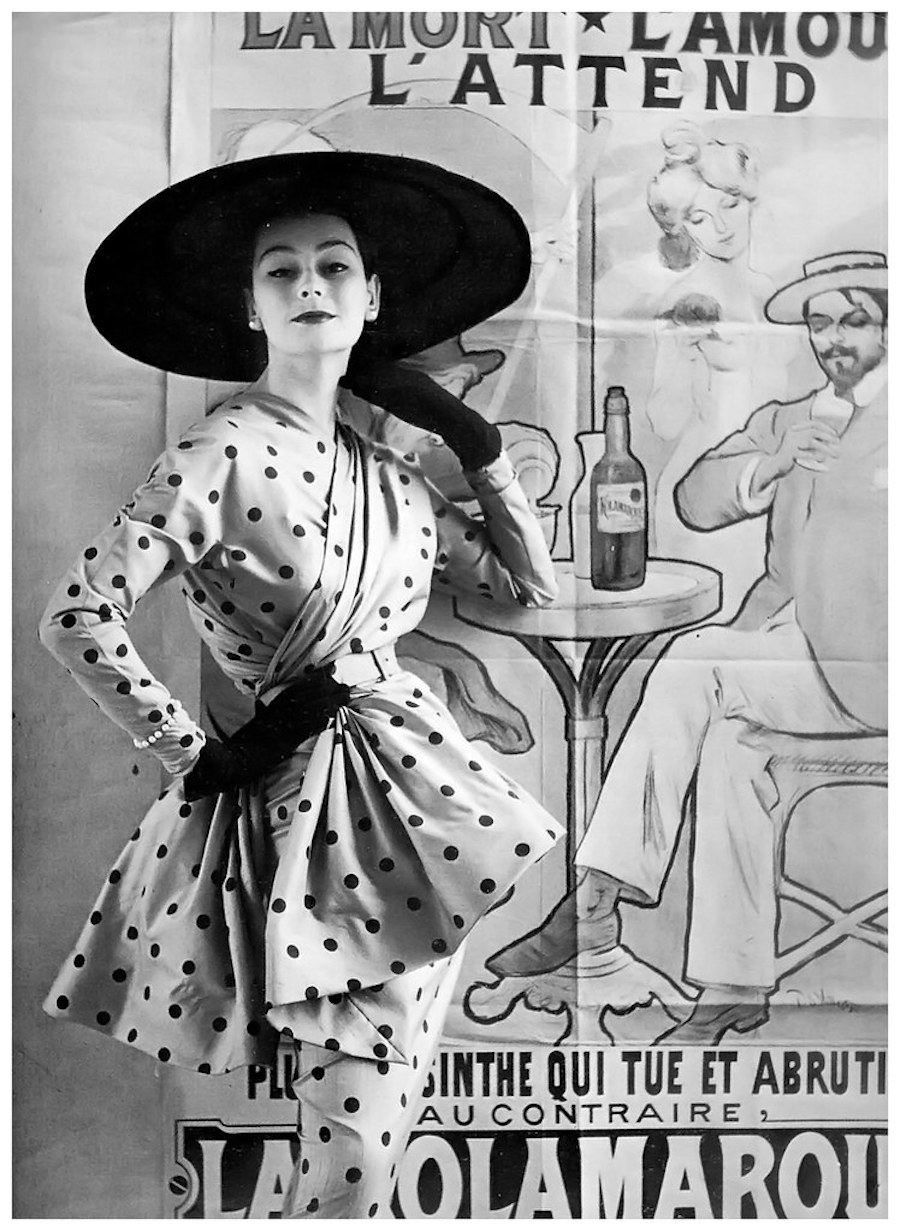

He also had the guts to boldly dabble in colour, and was drawn to what was considered ‘unfashionable’ shades at the time. Chartreuse, for example, was one of his preferred shades, as were purple, turquoise and apricot – this, at a time where soft, modest pastels were the preferred currency for ballgowns.

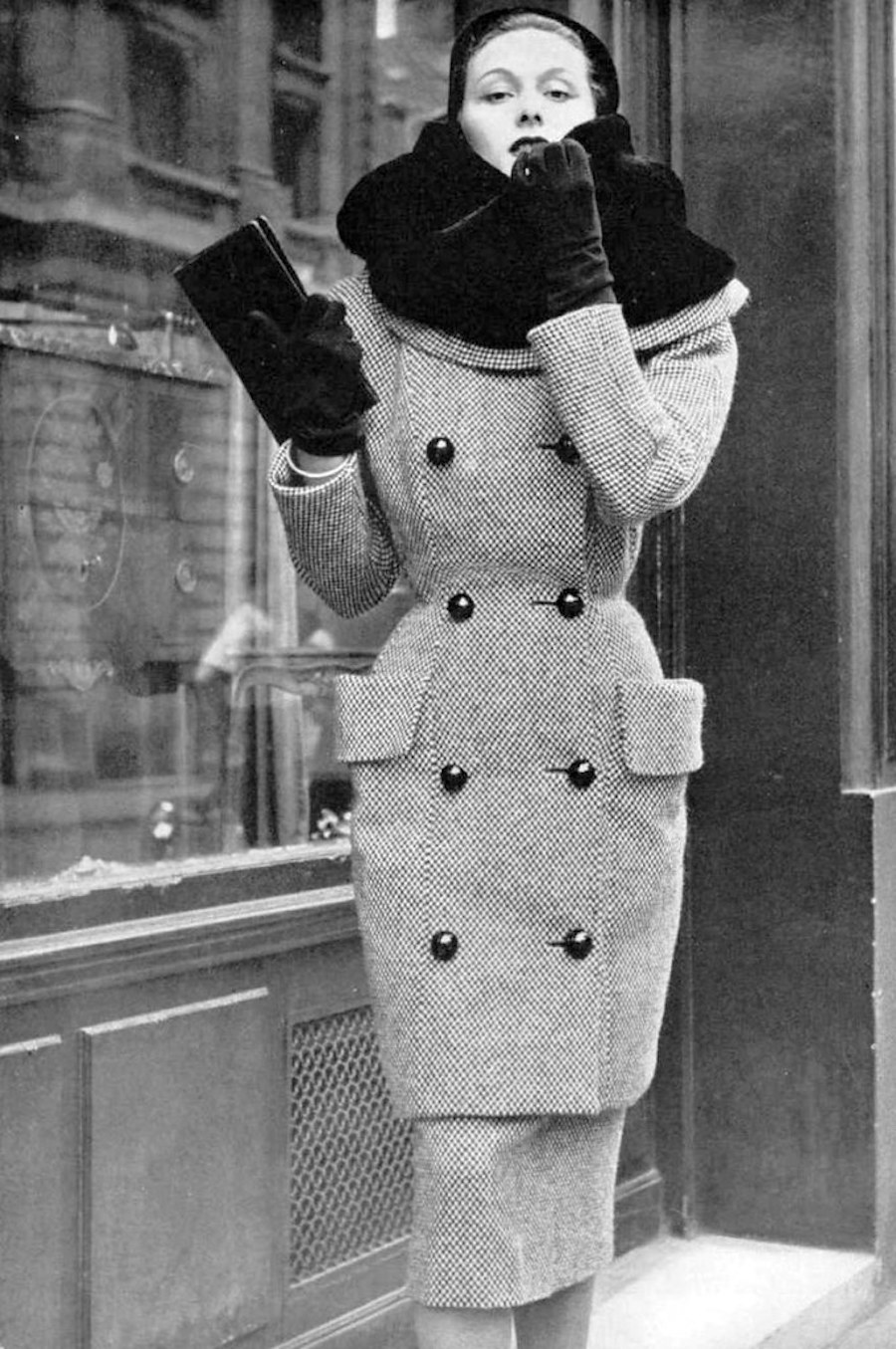

Although Griffe had a relatively long career as a designer, it was mostly his work in the fifties and sixties that shines the brightest. Griffe’s eye for detail and embellishments was second to none and his repertoire was vast: fringing, asymmetry, tulle tiering, peplums, 3-D sculpting, straps, ribbons, bows, embroidery, rhinestones and so much more would be called upon to enrich and adorn ensembles.

He had an uncanny eye for working with the qualities, properties and patterns of the various textiles to best accentuate the contours of the female form. His stripy swimsuits, for example, would follow the curves of the body perfectly to deliberately accentuate the hips, the diagonal fringing on a ballgown would subtly flatter the bust. He effortlessly switched between glamorous, Hollywood-style floor-sweeping gowns in the softest tulle and chiffon and neat and practical little day-suits in wool and tweed. When the sixties arrived with their shorter skirts and boxy jackets, Jacques Griffe responded, but always kept his garments cut close to the body, so as to at all times be flattering and feminine. In the 1960s a line called ‘Jet’ won various fashion awards for Griffe.

This unsung creative force kept churning out unforgettable treasures for women of all ages and all walks of life until his retirement. He passed away in 1996. His creations live on. The late Issey Miyake paid tribute to him in one of his latter collections and we’d wager that somewhere between Vionnet et Madame Grès, it’s only a matter of time before Griffe makes it to the front of the queue for a brand revival that other recently re-birthed industry names have seen in recent years. And the next time you automatically assume that the Cinderella-style fifties ballgown with its iconic silhouette of fitted bustier, impossibly nipped waist and voluminous skirt has Christian Dior written all over it, think again!