1. Keep everyone guessing with numerous aliases and identities

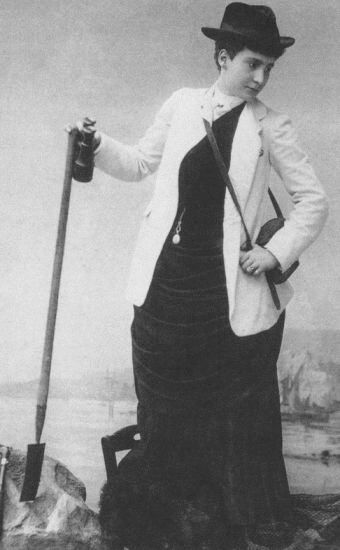

Mathilde de Morny presumed many nicknames. Friends called her “Missy”, but in her artistic endeavours, she also went by the pseudonym “Yssim” (an anagram of Missy). When dressed in men’s clothing, she preferred “Max”, or sometimes “Uncle Max” or “Monsieur le Marquis”. When she arrived in Paris in the 1880s, De Morny made her debut on the social scene wearing ball gowns, but soon found the confidence to defy social conventions not only through her relationships with women but also through experimenting with gender identity and embracing a masculine image. She was known to wear trousers under a removable skirt, which she could tear off and leave in the cloak room of Paris’ closed circle establishments. “Teetering between lesbianism and transsexuality”, to this day, she has kept historians guessing, even with Colette’s works as source material, “as to whether Missy could be classified as a butch lesbian or a transgender man.” (Dr. Kadji Amin, JStor). The French novelist Joséphin Péladan began his letters to her with “cher androgyne“ (dear adrogynous), and remarked “you have become your own brother”.

2. Make the most of an elite upbringing

The daughter of a French duke (and Napolean III’s half-brother) and a Russian princess (possibly Nicholas I’s illegitimate daughter), De Morny, born in 1863, was raised in the highest echelons of European society with traces of Romanov, Bourbon and Bonaparte in her blood. De Morny’s father died while she was still young, and after her mother remarried a Spanish duke, she grew up in the Spanish royal court. Her mother was cold with her, but she found friendship in her stepfather, with whom she hunted with and enjoyed bullfights. As soon as her mother died, she cut her hair short, wore top hats, men’s style three-piece suits from Savile Row and had a penchant for smoking cigars. This would have been especially shocking of during an era when women had to get special permission to wear trousers, but her wealth and status provided her a safe haven that wouldn’t have been afforded to others of a lower social class. As a person of privilege, she was able to live relatively open as a lesbian, defying stereotypical gendered presentations. In Paris, she married Jacques Godart, the 6th Marquis de Belbeuf, a move that earned her a title in 1881. Godart was gay, and the union provided them both with a convenient cover to pursue the people they were actually interested in. They eventually divorced in 1903, but always remained on good terms. Thanks to her fortune, De Morney was able to pursue the finer things in life as an aristocratic artist, dabbling in painting and sculpture.

3. Get them talking about your sex life

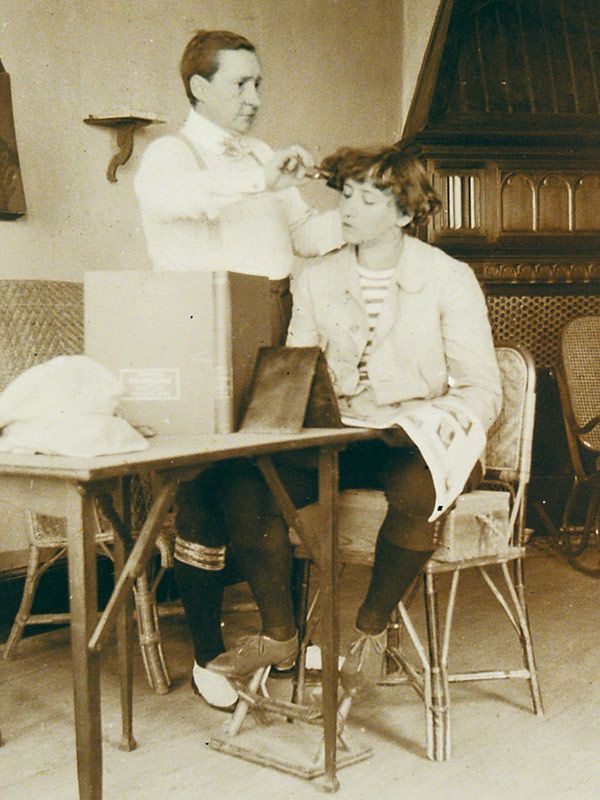

Part time artist, part time sapphic seductress, De Morny’s stories of romantic conquests circulated in the press and society circles. Her brother complained that she would steal away his potential mistresses. There were rumours that she bit off the clitoris of a female gardener in a fit of passion and had to provide her with compensation. Another story circulated that when her chambermaid died, she burst into the room where she lay lifeless, pleading to have her one last time. While de Morny didn’t shy away from having relationships with the working class, she did pursue relationships with some very high profile mistresses, including Colette and Liane de Pougy, a star dancer at the Folies Bergère cabaret. In 1906, De Morny and Colette were introduced by their mutual friend, Nathalie Clifford Barney (another queer pioneer of the Belle Epoque) and the women began living together soon after in a northern French villa called “Belle Plage.” This is where Colette wrote multiple novels, including Les Vrilles de la Vigne and La Vagabonde, about a divorced woman who becomes a music hall dancer. (French actress and director Musidora adopted the latter for cinema.) Colette and de Morny caused a scandal when they organised pantomime performance at the Moulin Rouge entitled Rêve d’Égypte (“Dream of Egypt”). De Morny, playing an Egyptologist, had a love scene with a woman, a kiss so scandalous that it led to the crowd rioting and the police had to intervene. Despite separating in 1912, De Morny continued to inspire Colette, including a character in her 1932 novel Le Pur et l’impur. Like de Morny, La Chevalière wore “dark masculine attire, belying any notion of gaiety or bravado… High born, she slummed it like a prince.”

4. Exercise like crazy

A libertine must keep fit for all that nocturnal frolicking, but going to the gym needn’t be boring. Keeping a home gym was practically unheard of in Belle Epoque Paris, but De Morny not only installed the necessary equipment to work out in the comfort of her home, she reportedly exercised in the nude in front of a select female audience. She was also a fan of boxing and fencing. On one occasion, she challenged a prominent Parisian playboy (whose mistress she had seduced) to a duel. Upon winning the fight, De Morny proceeded to rip open her shirt, exposing her breasts to make the victory against her unsuspecting male opponent that much sweeter.

5. Never let them break your heart

De Morny grew increasingly isolated later in life. After meeting Henry de Jouvenel, who would become her second husband, Colette left Missy in 1911, but kept their house. It is believed De Morny never recovered from the loss of her great love. This generous, courteous, melancholic being, suffering from a lack of affection since her childhood, died by self-asphyxiation, putting her head in a gas oven, at the age of 81. In 2018, she was portrayed by Irish actor Denise Gough in the film Colette. In a letter written while they were still together, Colette wrote to a friend:

“It’s still the Missy you know, the same faithful, honest and tender companion, who saved me, remember, from despair, from suicide no doubt, or perhaps, what would be worse, from the sad life of ‘kept women’.