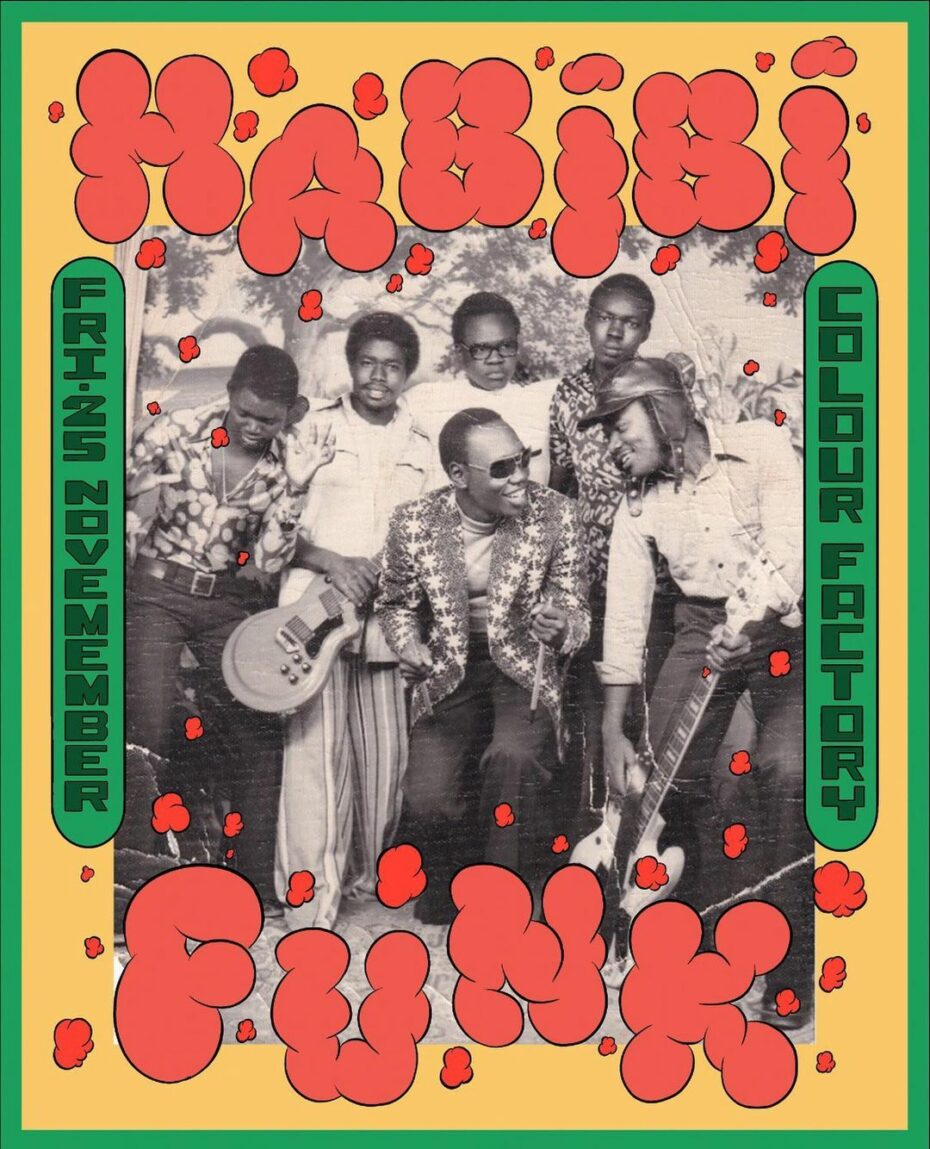

Perhaps you remember the feeling of unearthing a really great gem at the record store – a forgotten band from another time with an original sound that sends those feel-good electric impulses to your brain. Habibi Funk is one of the few indie record labels bringing the sound of the Arab music world to the west, both re-releasing and creating music somewhat lost to time. When you look into the label, it might not be immediately evident that the operation is led by a westerner from Berlin, but Jannis Stürtz makes himself a figure of the background, working to highlight and uplift musicians from the Middle East and North African diasporas. Habibi, meaning “my love,” or “my dear” in Arabic, is the embodiment of what this project has meant to musicians spanning several generations. From Disco Arabesquo and Libyan reggae to Egyptian Jazz and Lebanese folk, the songs compiled by the record company and available to stream on Spotify are a little bit of everything, curated for whatever you’re craving. So if you feel like your ears need a fresh sound, discover the world of Habibi Funk with us…

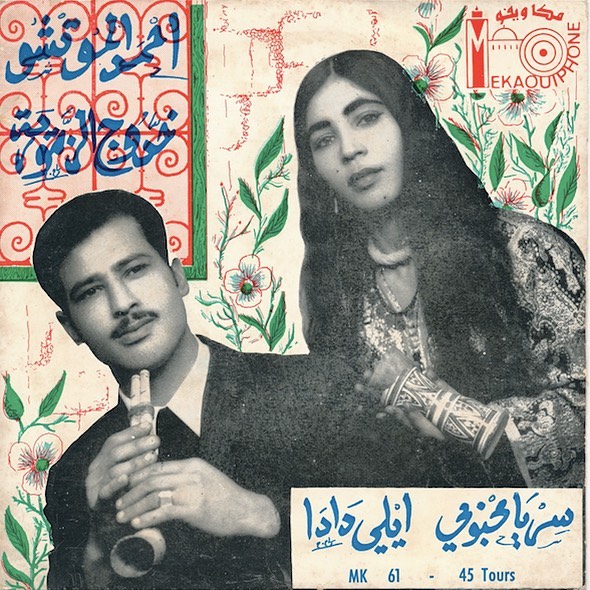

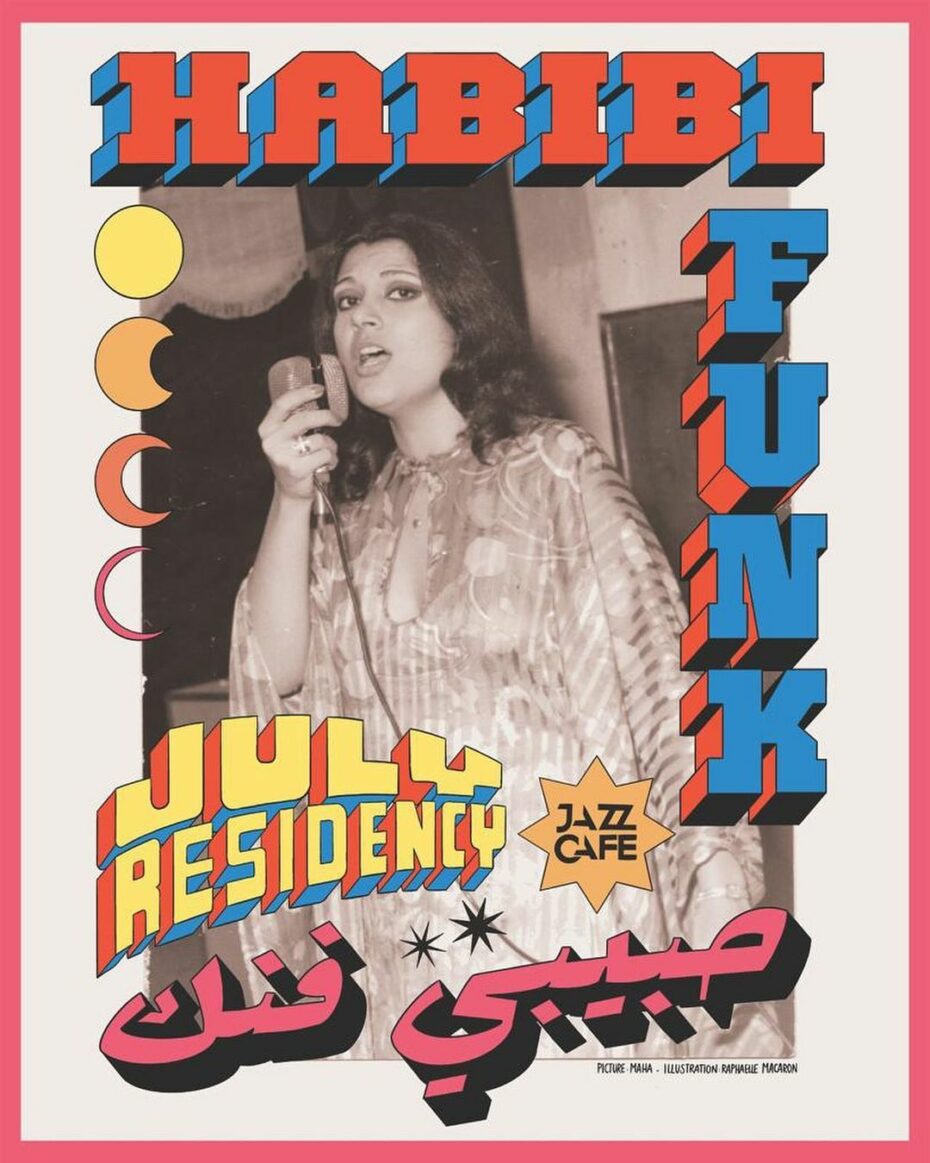

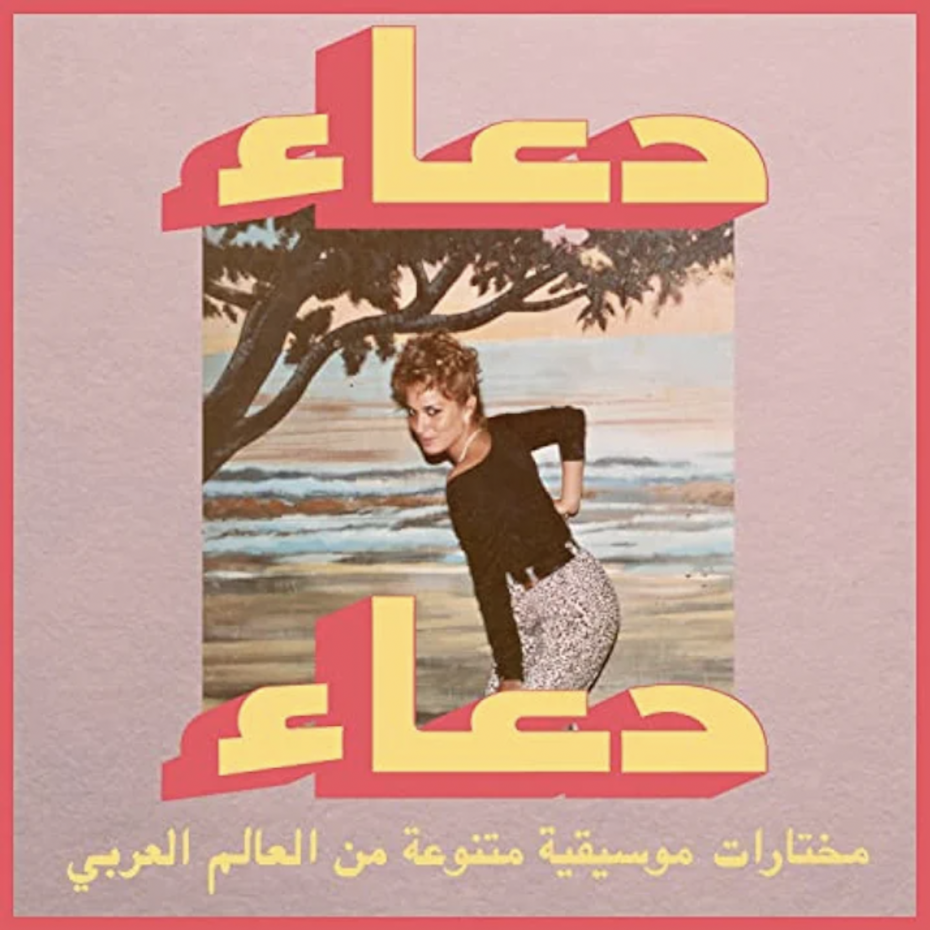

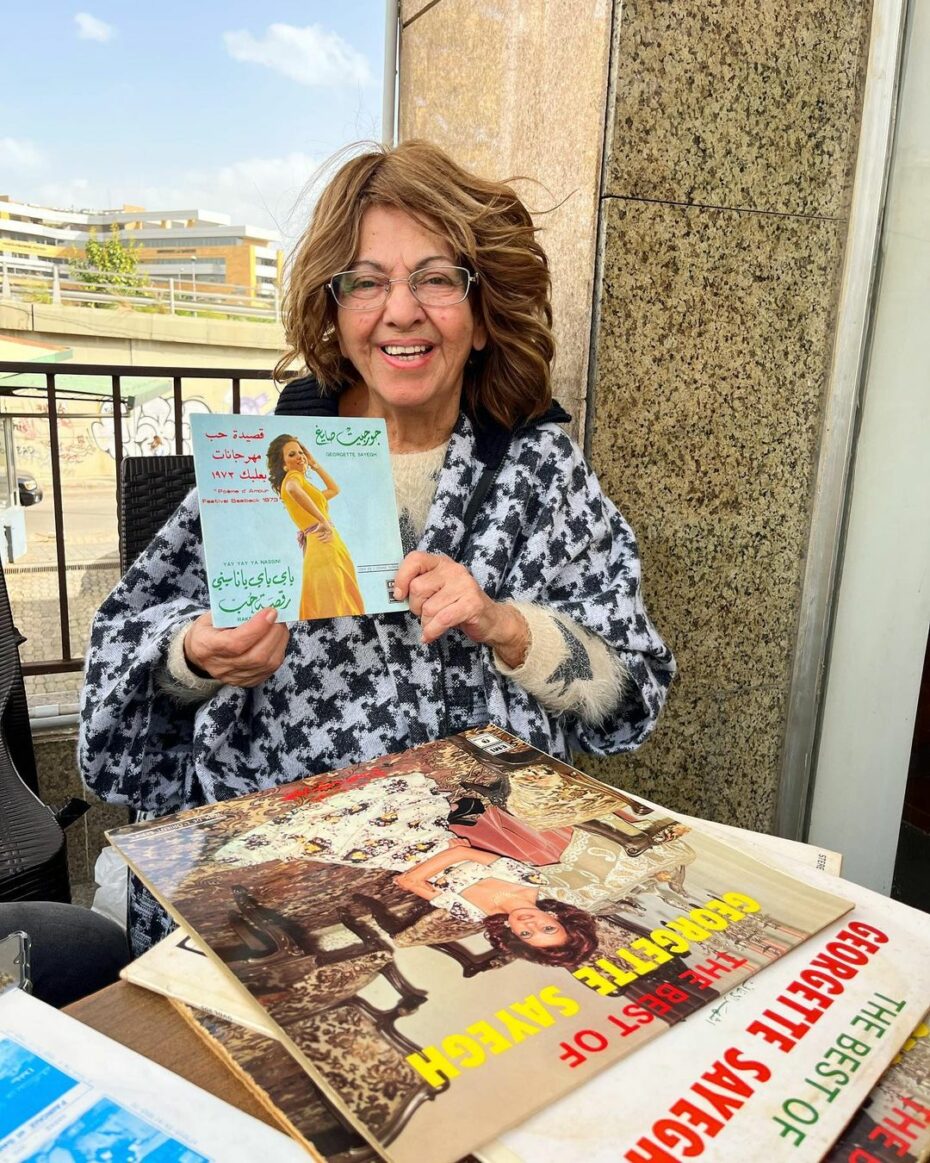

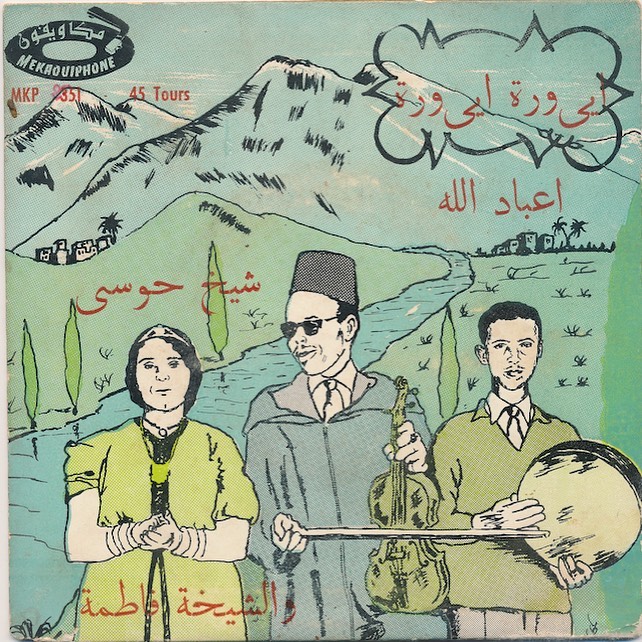

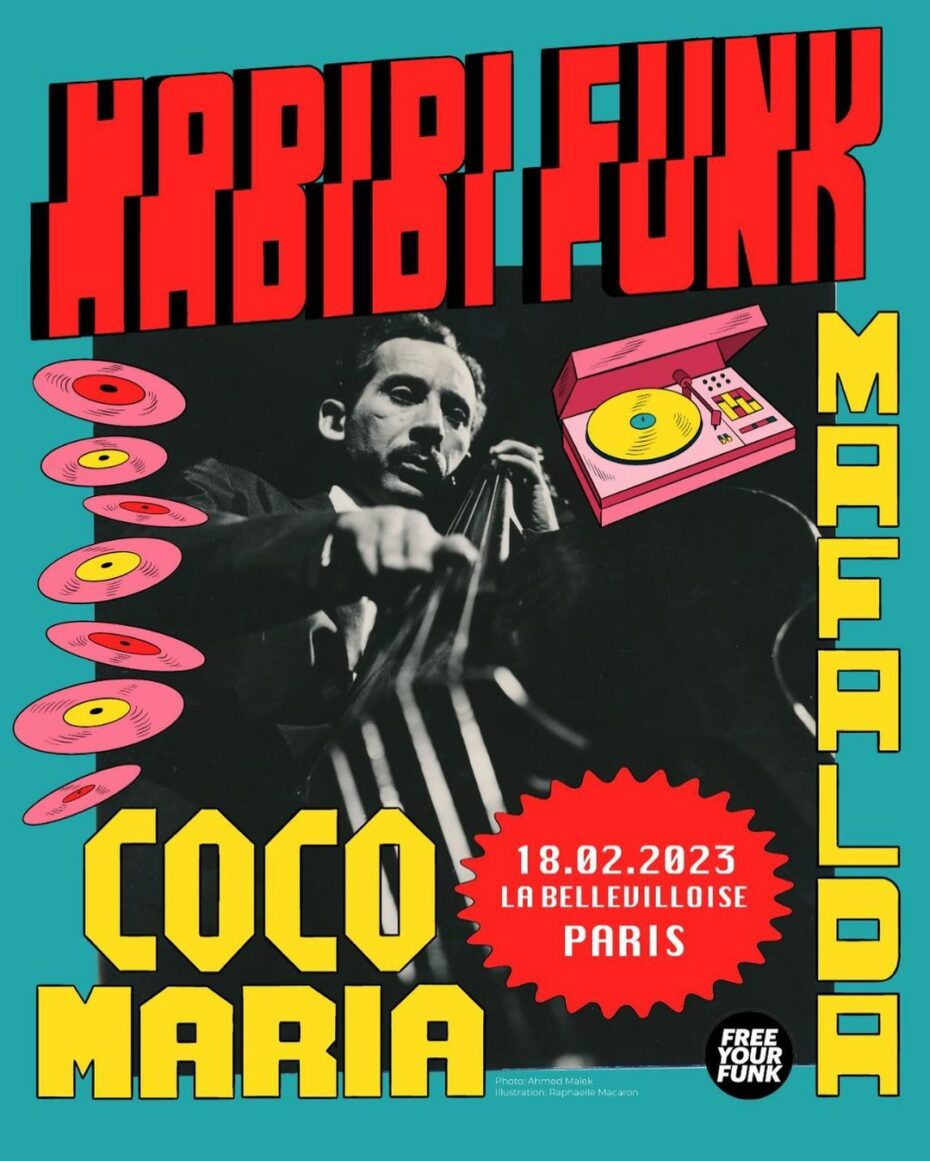

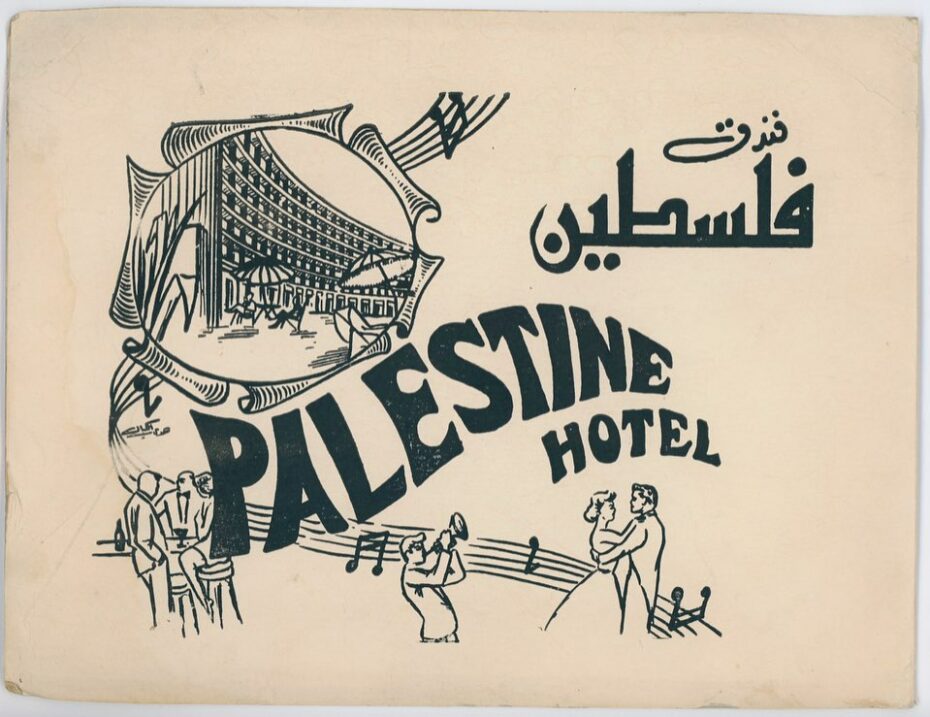

The label strives to reproduce music (while aiming to avoid using the word “discover”), which may not have only been lost to time or through distance, but also deprived of its own designated musical genre. Habibi Funk aims to fix that, introducing forgotten sounds and genre identification to a new generation through careful curation online, live events and physical releases with fresh yet nostalgic album artwork heavily inspired by Middle Eastern vintage recording graphics, which has become a recognisable signature of the label’s branding. Over the past decade, Stürtz’ label has released 26 albums of mixes, re-releases, and original work, giving a platform to guest Middle Eastern curators too, highlighting artists from countries like Libya and Egypt.

While rising from the underground, the label is also responsible for that catchy music on the opening of the hit Hulu show “Ramy.” The label connected the show creators with some of the Egyptian artists who wrote the soundtrack throughout the first two seasons. The collaboration would catapult one of Egypt’s first pop bands, Al Massrieen, back into the spotlight after several decades in the shadows. Here’s “Longa 79,” that famous catchy sound we love from the show:

Al Massrieen, which literally translates to “the Egyptians,” was making waves in Arab pop at the end of the 1970’s. They revolutionized music in Egypt without playing western pop covers. The group sang in Arabic and used Egyptian based cultural themes to compose their tracks, paired with modernised sounds on electric instruments. Shenoda, the mastermind behind the group recalled, “Our music is revolutionary in its tune, in its arrangements, and, of course, in its lyrics. We transformed Egyptian music from being monophonic music, where the singer and the orchestra would play the same note, to polyphonic music that makes the keyboard, the bass, etc etera, play different notes. This is the change we made and that was the base we gave to modern Egyptian music.”

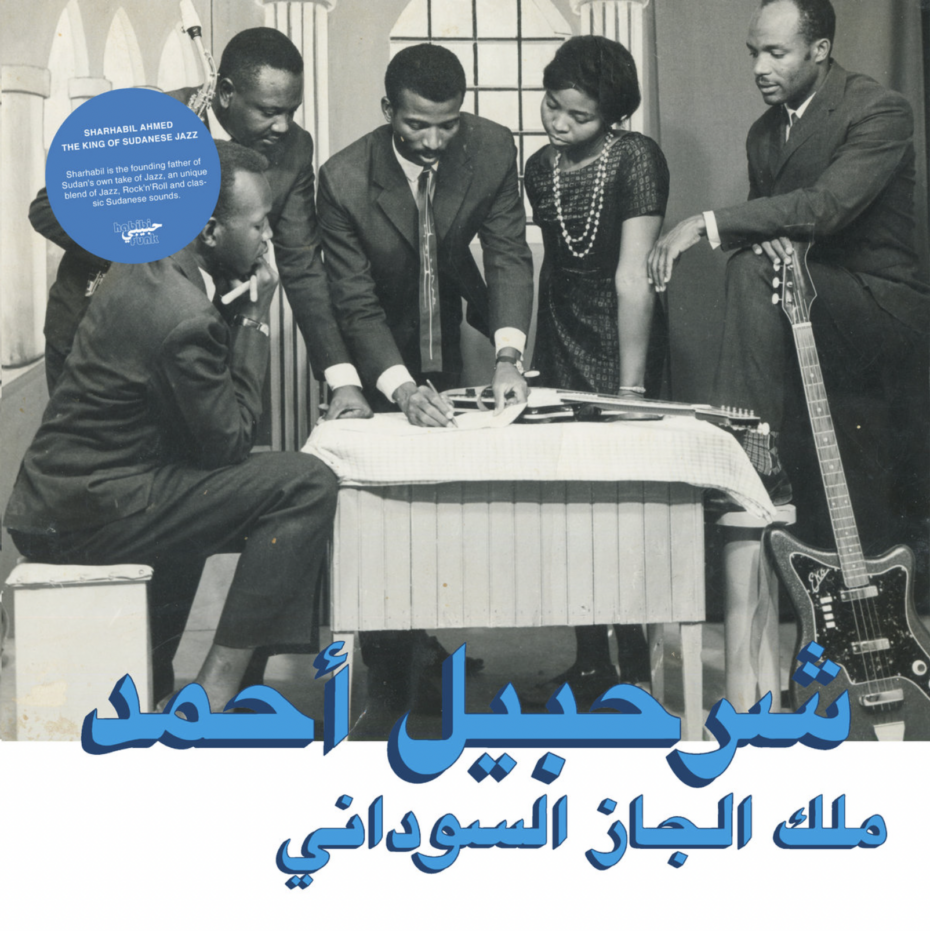

Work produced by the many artists represented by the world of Habibi Funk was created during conflict, war, economic hardship or circumstances of exile. Some of those lost artists include Sharhabeel, a Sudanese artist who made waves in the 1960’s through radio, with few recordings left to show for his career.

Jan talks about how the re-release of his music came about:

“In our conversation, it turned out that even though his career seriously started in the 1960s, he had never released a record on vinyl and that, apart from one album which still remains to be found, he can’t remember about a cassette tape release either. He did however record sessions for Sudanese radio. In Sudan the radio stations were not allowed to play the recordings produced by music labels on air, therefore they had their own studios and invited musicians to record music for their program. In most cases the musicians would not receive a copy of the recordings out of fear that they would release the music themselves. But luckily Kamal Keila had gotten his hands on two sessions and had kept those two studio reels all these years. Both tapes were in the most horrible condition with mould everywhere and obvious signs that they had gotten very wet at some point. Much to our surprise they played very well … His lyrics, at least when he sings in English which indicates more freedom from censorship, are very political. A brave statement in the political climate of Sudan of the last decades, preaching for the unity of Sudan, peace between Muslims and Christians and singing the blues about the fate of war orphans called Shmasha“.

Many of the artists which are represented today by the label are ageing or have passed away. The group operates on a 50/50 profit share, while only producing music when given permission either directly by the artist or by the family of the deceased. Each record released has an equally fascinating story about how the artists or their descendants were tracked down by the label.

When Stürtz came across the work of Ahmed Malek, a highly decorated Algerian composer and conductor who dominated the 1970’s and wrote the music for dozens of movies, television shows and documentaries, it seemed the artist’s trail had gone cold. Others tried and failed to gain the licensing rights to the music because no one could track down his family but with a stroke of luck, Stürtz seemed to know the right people. “I did a DJ gig in Beirut and a friend of mine came to the show. We were talking about Ahmed Malek and how I’d like to do a reissue. I said I didn’t have a clue how to find the family. She said, ‘I have a friend in Algeria, I’ll just ask her’. I was like, ‘yeah, there are 40 million people in Algeria, what are the odds?’ Two weeks later she calls me, and it turns out her friend’s family live in the same building as Ahmed Malek’s daughter.” Thus a magical partnership was born.

The label stresses the fact that the sounds and styles they represent are reminiscent of what westerners may feel familiar with but that these artists didn’t necessarily use the west as the blueprint for their sound. Simultaneously, the music which they have produced is not entirely representative of what was popular in the Arab world from the 60’s-80’s either.

“Some of our favourite records are best described as Arabic zouk (a genre originating from the Caribbean islands of Martinique and Guadeloupe) like Mallek Mohamed’s music, Algerian coladera (a popular musical style from the Cape Verdean islands) or Lebanese album-orientated rock.”

One of the most beloved albums released to date is the collection called Habibi Funk 007: An eclectic selection of music from the Arab world. The sound of the tracks are both familiar and comforting as they are refreshing and completely something else all on their own.

The label’s founder stresses that, “In today’s world there are still many stereotypical conceptions to be found when it comes to the Arab world. Contrary to what a lot of western narratives and media suggest, the Arab world we got to know through extensive traveling in several countries of North Africa and the Middle East, is a very versatile terrain. A place full of different stories, ideas and beliefs. And we hope that the music we release helps as a tiny, tiny piece of a larger puzzle to establish a diverse, more nuanced yet adequate idea of how musically vibrant this very diverse region once has been and also still is. At the same time we do not want anyone to misunderstand this compilation as a selection of songs to represent Arabic musical history of the 1970s and 1980s. This compilation is nothing more than a very personal curation of songs we like and in no way reflects on what has been popular in a general sense.”

One of the artists who initially inspired the creation of the 007 compilation is an artist named Fadoul. If you’re a fan of that James Brown sound, Fadoul is your guy. He is revered for singing “I’ve Got a Brand New Bag,” in Arabic, mixing a little bit of the west with a Moroccan flair – recording funk following a stint in Paris where he discovered the beloved American genre.

You can listen to 007 here:

Something seemingly special about the world of Habibi Funk is that they work to keep ethics at the forefront of their business. All of their instagram captions for examples are written in english and then translated into Arabic. They also have a designated section to ethics in which they have saved and answered questions from the public about why they operate in the ways they currently do. They come from both angles – owning that they are outsiders to these cultures and looking to uplift them while recognising the importance of remaining aware and steadfast about the history of colonialism between them.

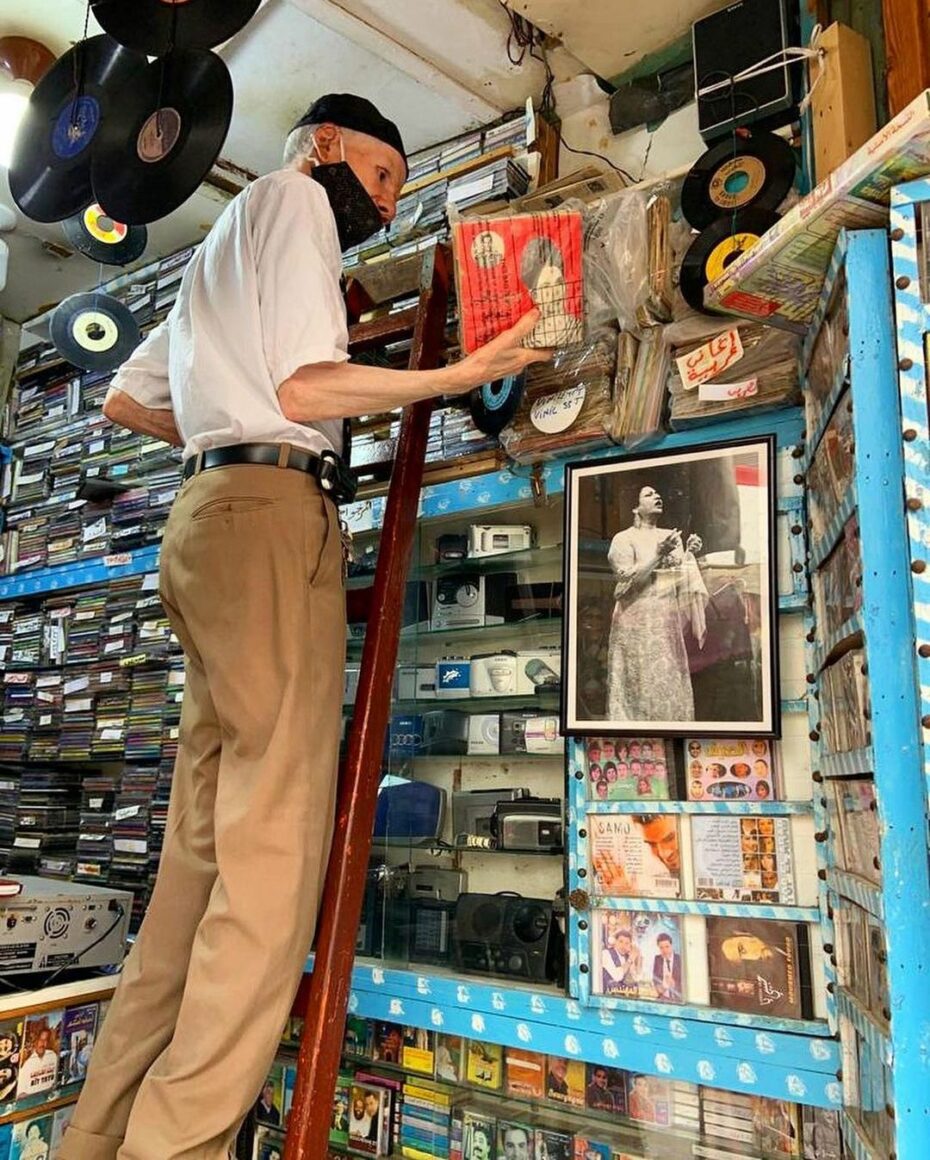

Following the Habibi Funk instagram account is also for lovers of vintage ephemera. The label’s team is constantly sharing interesting finds in their pursuit of sound, such as these Egyptian night club business cards. The account also advocates supporting independent record stores and keeps an updated list of gems to find in cities like Marrakech and Cairo.

Not only is the world of Habibi Funk one which brings the west previously inaccessible gems of music, but it celebrates and empowers creatives in a mindful effort towards their respective cultures. The label is helping to share Arab music with the west not only for the good jams but also for breaking down stereotypes about what the Arab world values, who they are, and what they represent.

Not sure where to start? Here’s a handy list of introductory albums recommended by Somewhere Soul:

1. Ahmed Malek – Musique originale de films (Habibi Funk 003)

2. Charif Megarbane – Marzipan (Habibi Funk 023)

3. The Scorpions & Said Abu Bakr – Jazz, Jazz, Jazz (Habibi Funk 009)

4. Roger Fahkr – Fine Anyway (Habibi Funk 016)

5. Hamid Al Shaeri – The SLAM! Years: 1983 – 1988 (Habibi Funk 018)

6. An Eclectic Selection of Music from the Arab World (Habibi Funk 007)