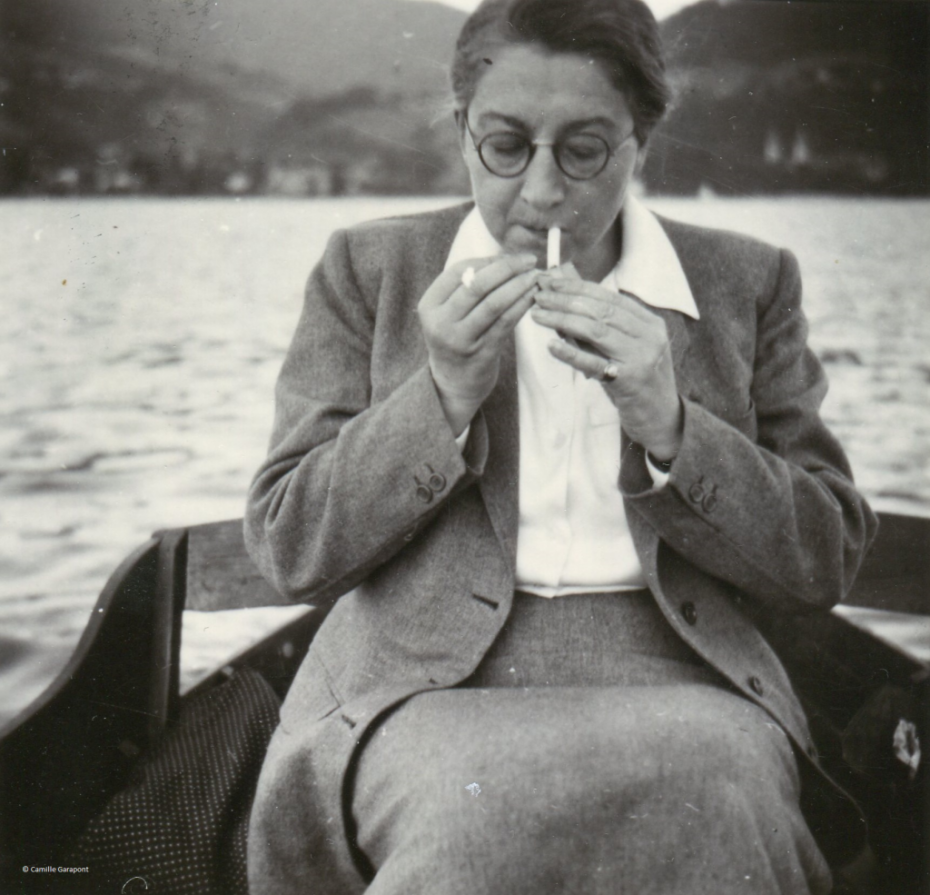

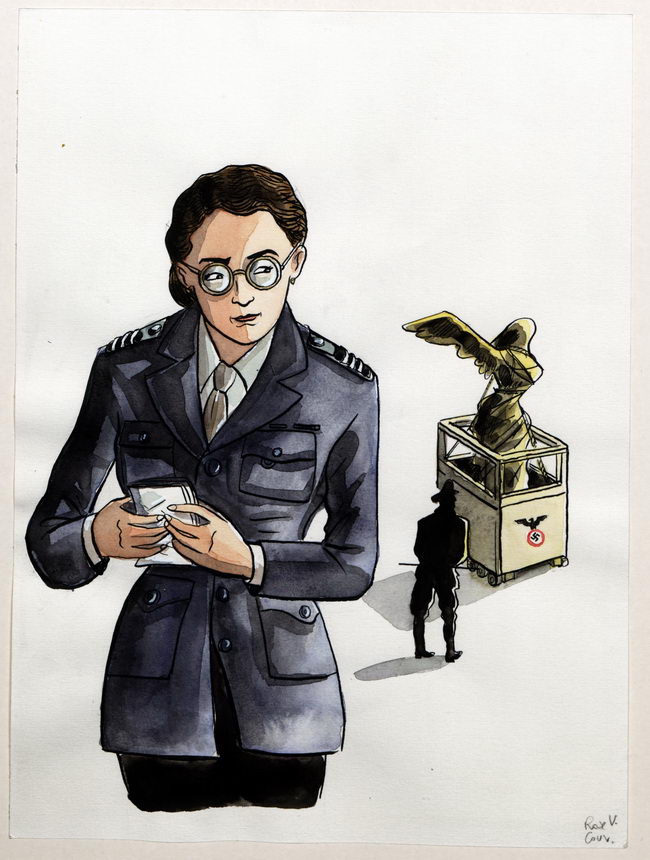

At first glance she looks like just another bookish art historian in matronly 1940s garb – a most unlikely superhero. But Rose Antonia Maria Valland was a lone female spy who, during WW2, tirelessly and valiantly put her life on the line for the love of art, saving scores of looted works of art during Nazi occupation. In 1940, the museums of Paris with their invaluable art collections together with that of private collectors, fell prey to German wartime greed, with systematic raids orchestrated by Hitler’s art-looting arm. At the time, Rose Valland worked as a curator at the Jeu de Paume Museum in Paris’s Tuileries Gardens. It so happened that Hitler made this very museum the sorting for his art-looting organization, Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR) and the place where much of the confiscated art and artifacts would be stored before they were expatriated to Germany.

Vallard’s boss and director of the French National Museums, Jacques Jaujard, thought Vallard with her unassuming appearance would make the perfect undercover agent. A mousy, bespectacled spy on a secret mission to keep tabs on looted art. A handy and rather well-kept secret was that she also happened to understand the German language. Rose kept meticulous records of over 20 000 pieces of art, artifacts, silverware, jewellery and other valuables that were squirrelled away to the halfway house at the Jeau de Paume museum (a former tennis court for the royal court). As the plundering continued, she harvested intel on artworks that were taken directly to railway stations by speaking to unsuspecting German truck drivers, all the while relaying this information to the museum’s director. Throughout the war, she kept tabs on the logistics of incoming and outgoing artworks, recording where to and to whom they were being shipped in Germany, risking her life to keep the French Resistance movement informed. Allegedly Rose Valland was also at the museum to witness Goering personally picking out art for his private collection on May, 3rd, 1941.

Extraordinary intel came on August, 1st, 1944 (and just prior to the Liberation of Paris on August 25th, 1944): the head of the ERR in France, Heinrich Baron von Behr, was plotting a major exodus of artworks, including modern works of art which the Nazis hadn’t been interested in up to that point. To her horror, Valland discovered that 148 crates filled with 967 paintings, including works by Gauguin, Modigliani, Picasso, Toulouse-Lautrec ,Braque, Cézanne, Degas, Utrillo and Dufy were being loaded into five wagons at the train station at Aubervilliers, Paris. This exceptionally valuable scoop was awaiting being hooked onto another 48 wagons filled with all sorts of confiscated private artefacts and possessions, ready to leave for Germany. Thankfully, due to a delay in loading, the train didn’t leave the station on schedule. Vallard passed on a copy of the shipment order complete with details like the wagon numbers, the contents of the crates and where each goods wagon was heading to Jaujard, who in turn forwarded it on to the French Resistance. As luck would have it, the French railway workers were on strike when the train was finally ready to depart, on August 10th, 1944. A couple of days later, when the rails were cleared, there were further delays with Germans fleeing on high priority trains. The overloaded train with artworks eventually departed but suffered a mechanical breakdown, and by the time the Germans had fixed the problem, the French Resistance managed to derail two trains, blocking the tracks and leaving the art cargo in limbo. This enabled the Second Armoured Division of the French Army to secure the train. Under a Lt. André Rosenberg they despatched 36 crates to the Louvre for safekeeping, but it took a further nerve-wrecking two months before the remainder of the crates were moved to safe storage.

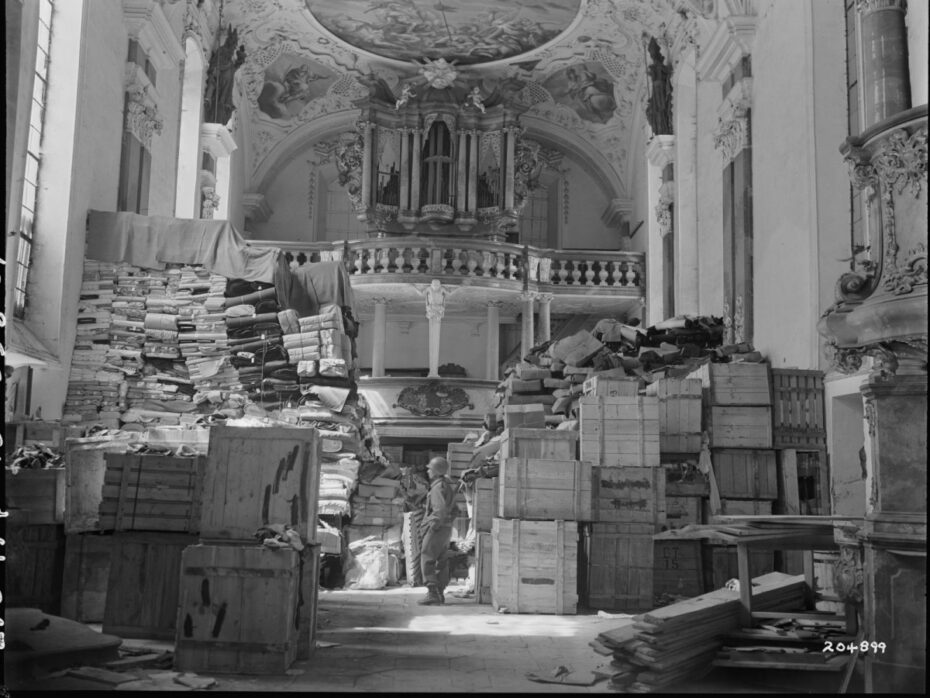

Once the Allied Forces had liberated Paris, Rose Valland was arrested as a suspected Nazi collaborator because she had been working at the headquarters of the ERR, but was soon released. She was understandably reluctant to share her records with anyone but Jaujard, however did eventually trust Captain James Rorimer in charge of the Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives initiative enough to disclose her secret information. This enabled the discovery of numerous secret locations where art was stowed away, for example, Neuschwanstein Castle in Bavaria where more than 20,000 prominent pieces of art were unearthed. Not only did Valland personally assist in returning artworks to Jeu de Paume, but she also helped reunite private artworks with their respective owners.

Rose Valland was made lieutenant, then a captain in the French Army at her request in 1945, to facilitate her efforts in locating and returning stolen artworks. She served in Germany for 8 years, where she was the French government’s direct liaison. She was also a witness at the Nuremberg trials in 1945, where she challenged Goering on the artworks he personally stole from France. She was put in charge of the French Oversight Board in 1946, from where she recovered priceless French art, tapestries, sculptures, coins and other artefacts. With her help 60,000 pieces of art were returned to France before 1950.

Highly decorated during the war, her heroism has since inspired many books and films, including The Monuments Men, in which Cate Blanchett played a character based on the heroism of Rose. In 1961, wrote about her experiences in a book entitiled Le front de l’art (not published until 1997) and retired in 1968, but never stopped contributing to restitution. Her lifelong efforts were recognised and she received numerous accolades and awards from France as well as other countries, even the Medal of Freedom from the USA in 1948.

After the war, Rose Valland had a personal relationship with Joyce Helen Heer, a British woman who was a secretary at the United States embassy. The two shared an apartment on rue de Navarre in the 5th arrondissement, Paris. Valland died in 1980 and the central square in her hometown of Saint-Étienne-de-Saint-Geoirs was named after her, as was a college. A commemorative plaque in her name was unveiled at the Jeu de Paume in 2005 and the French postal service honoured her with a stamp in 2018.

To this day, the initials MNR (Musées Nationaux Récupérations) are seen on around 2,000 works of art in French museums that vanished during the second World War, and whose legitimate owners have not been identified, as they themselves may also have ‘disappeared’. Sara Houghteling’s novel, Pictures at an Exhibition (2009) ends with a paragraph and a touching tribute to the hand of Rose Valland in the preservation of French art for posterity;

If you are ever in France, and from a distance you see a painting that looks roughly handled for a masterpiece – in the Musée d’Orsay, or any of the other hundreds of museums – look closely at the placard beside it, and you will likely see the letters MNR.