The sex industry was one of 18th century Britain’s most lucrative enterprises, and the women and girls at the centre of this trade enraptured the nation, endlessly feeding society with tantalising tales from behind closed doors. But all too often, their voices have been left down the back of history’s sofa, largely due to the powerful men who preferred their own seedy practices to remain hidden from record. So let’s shift the spotlight. With a flair for the dramatic and a penchant for turning heads, Kitty Fisher wasn’t just the talk of the town in Georgian London, she was its undisputed queen – and folks really loved to hate on her. In an era without Instagram, Twitter, or TikTok, this 18th century courtesan mastered the art of personal branding, using nothing but word of mouth, the printed press, and a healthy dose of charisma to cement her place in history as the original influencer.

Born Catherine Maria Fisher in 1741, Kitty Fisher debuted amidst the hustle and bustle of London’s vibrant streets. She was the daughter of a humble tradesman, lacking the pedigree and noble birth that often served as the ticket to high society. However, Kitty possessed something far more valuable than titles or lineage — she had wit, beauty, an insatiable thirst for adventure, and mastered the art of self-creation, turning her personal brand into a phenomenon that commanded attention and admiration far beyond the usual confines of aristocratic circles.

Kitty’s rise to fame was nothing short of meteoric. The 18th century was the start of the modern day celebrity culture that we know and love today – or rather the culture we love to hate and hate to love. From a young age, Kitty displayed a natural aptitude for captivating those around her, regardless of their social standing. At the tender age of 16, Kitty Fisher entered London society via a gentleman of high military rank, setting tongues wagging with her grace and poise, but when her lover was sent abroad, Kitty was left alone to navigate the Georgian social scene. She quickly caught the eye of several other prominent gentlemen however, including politicians, artists, and wealthy aristocrats, and sought out wealthy patrons who would pay for her company; Lords and admirals and generals.

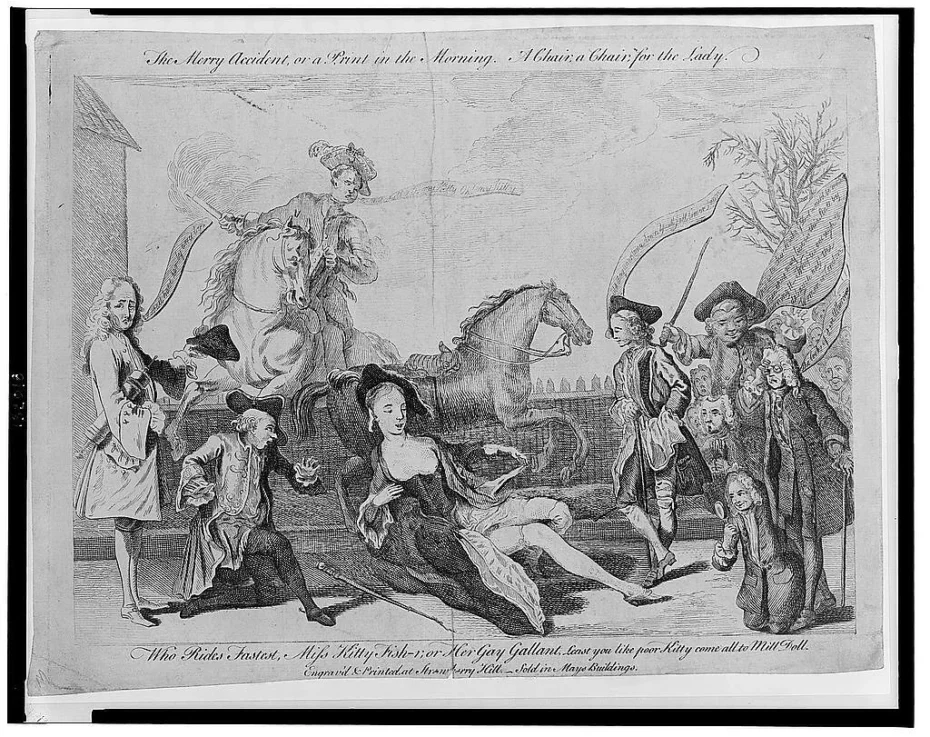

However, it was not just her beauty and romantic entanglements that captured the public’s attention: Kitty Fisher was a master of self-promotion. Curiously, she was very accident-prone and people wondered whether she staged several of her news-worthy accidents (usually involving a horse). One might refer to these today as “publicity stunts”.

During a leisurely horseback ride through Hyde Park in 1759, she donned a stylish black habit and rode her frisky horse towards St. James’s Park. Although her ride was part of her usual routine, that day, some soldiers spooked the piebald, and the horse bolted. Kitty was thrown from her horse and accidentally exposed herself to a crowd of onlookers. The event was captured by caricaturists – the 18th century paparazzi – and plastered all across the London papers.

“…The nymph was in tears, but rather owing from Apprehensions of her Danger than the sense of Pain … she, with a prity childishness, stopped the torrent tears, and burst into a fit of Laughing. […] A superb Chair soon arrived, […] she flung herself into it, and away she swung through a Crowd of Gentlemen and Laides, who by this time were coming up. A sort of murmur was heard: but one Gentleman louder than the rest, spoke up …. Why ’tis enough to debauch half the women in London!”

The stunt laid the groundwork for what would, centuries later, inspire Hollywood starlets like Marilyn Monroe to “accidentally” expose themselves to hungry paparazzi.

She became very rich, very quickly, which naturally, rubbed a lot of people the wrong way. By the age of 19, she was one of the most famous women in the country, described as “the most pretty, extravagant, wicked little whore that ever flourised…” to quote a letter from Tom Bowlby to a friend.

While still a teenager, Kitty had become the woman everyone knew, or at least pretended to. All of London was talking and reading about what she was wearing and more importantly, who she was bedding. She was certainly a muse for the print culture at the time, even inspiring anonymously penned satyrical literature like the Juvenile Aventures of Kitty F.

One particularly salty observer was an anonymous writer who went by the name “Simon Trusty” and wrote an open letter to her, and the whole of London. Have a read:

Rather than shrink from the ridicule, Kitty Fisher turned the tables on her detractors. She enlisted the talents of England’s most prominent painter at the time, Joshua Reynolds, to immortalise her in several portraits that were not merely representations of her physical beauty but also reflections of her indomitable spirit and magnetic allure. And they were packed with visual puns.

In one painting, she is seen posing with a goldfish bowl, which discretely shows the reflection of a window where a flock of nosey fans and haters are trying to see in. Amusingly, the portrait also contains a kitty … fishing. In another portrait, she posed as the Egyptian queen Cleopatra, who at the time, was not only viewed as a fascinating historical figure with a dangerous edge but also treated as a trope for rhetorical absurdity. Prints of the engravings of her portraits were sold to thousands, which also earns her the title of one history’s first “pin-up” girls. The Cleopatra painting showed Kitty about to imbibe the largest pearl ever known, likely a response to a rumour that quickly turned into a London legend, claiming that she once swallowed a banknote (some say it was 100 guineas) folded inside of a sandwich because she was insulted by the “lowly” sum offered by a client in her boudoir. Even the infamous Giacomo Casanova (yes, that Casanova) referred to the money sandwich incident in his correspondence.

Casanova found himself drawn to Kitty Fisher’s magnetic allure but was allegedly immune to her charms due to her ability to speak only English – French was a prerequisite in Casanova’s book for making love. When he had met her, he wrote:

“We went to the Walsh woman’s, where the celebrated Kitty Fisher came to wait for the Duke of xx, who was to take her to a ball. She had on over a hundred thousand crowns’ worth of diamonds. Goudar told me I could seize the opportunity to have her for ten guineas, but I did not want to do so. She was charming, but she spoke only English. Accustomed to loving with all my senses, I could not indulge in love without including my sense of hearing. La Walsh told us that it was at her house that she swallowed a hundred-pound banknote on a slice of buttered bread which Sir Richard Atkins, brother of the beautiful Mrs. Pitt, gave her. Thus did the Phryne make a present to the Bank of London.”

Other sources report it was Kitty who turned down the famous Venetian lover, and an April 1770 edition of Town and Country magazine claimed Kitty spoke fluent French.

Kitty didn’t lack for aristocratic lovers, though, and she was often the ‘other woman’ for married noblemen, adding more scandals to the notches on her bedpost. One of Kitty’s greatest rivals was the wife of her lover, the 6th Earl of Coventry, Maria Gunning, who was also of lowly birth and, unlike other aristocratic wives, did not look the other way. Their rivalry between Maria and Kitty became quite the talk of the town. Giustiniana Wynne, a friend of Casanova, chronicled the confrontation between Miss Fisher and Lady Coventry:

“The other day, they ran into each other in the park, and Lady Coventry asked Kitty the name of the dressmaker who had made her dress. [Kitty Fisher] answered she had better ask Lord Coventry as he had given her that dress as a gift. Lady Coventry called her an impertinent woman; the other one answered that her marrying a nutty lord had put enough social difference between them that she would have to withstand the insult. But she was going to marry one herself just to be able to answer back to her.”

And so Kitty did just that. Although she cultivated quite a wild reputation, she ended up an “honest woman” when she married John Norris in 1766, the son of a Member of Parliament. She left her raucous London life behind, moving to her husband’s family estate of Hemsted Park – now the site of a respected private school – and rather enjoyed her role as mistress of the household. Although she seemed to have landed on her feet, her life was cut short at the tender age of 26 in 1767. The cause? Lead poisoning from the very cosmetics that had enhanced her beauty and mystique. There are some historians however who believe she died from good old-fashioned smallpox or tuberculosis (and that it was Maria Gunning who died from lead poisoning). Kitty was buried in the local churchyard sporting her best ball gown. Even in death, Kitty had to be stylish.

Very little solid information on Fisher is known, which is surprising considering her celebrity status and legacy, but it was likely an intentional strategy of Fisher in order to keep some semblance of privacy, but also an air of mystery, which might arguably be the true secret of celebrity sex appeal. This 18th-century dazzler was not just a footnote in history but the blueprint for today’s digital darlings. With her bold maneuvers, scandalous liaisons, and an impeccable sense of style, Kitty didn’t just walk into the limelight; she owned it, teaching us all a thing or two about the art of influence. Before hashtags and viral videos, there was Fisher, turning heads and setting trends with nothing but her wit and a flair for theatrics. Her legacy, dripping with sass and savvy, is a sparkling reminder that while the tools of influence have evolved, the essence of captivating an audience is timeless. So, here’s to Kitty Fisher, the original queen of influence, who proved that with enough charisma and cheek, you can indeed become immortal in the eyes of the world.