Django Reinhardt was a legendary jazz musician and considered by some the greatest guitarist who ever lived, even more so when you find out he did it all with two fingers. He began as a nomadic busker before becoming a virtuoso and then a romanticised Parisian sepia memory, who still calls out in rolling arpeggios from the grooves of a crackling wax disc. A Romani nomad who would overcome great adversity in life to astound audiences with his genius and technique, he would influence all that would come after him with woven melodies that danced and sang from his fingertips. He would travel a murky road through prejudice and fame, and then survive Nazi occupation through World War II only to succumb to a brain hemorrhage at age 43. He is remembered as the embodiment of European jazz and a cultural icon of musical freedom. Let’s put the spotlight on Django…

Born Jean Reinhardt on the 23rd of January 1910 in Belgium, to the Manouche, part of the Romani people, he would go by his other name of Django all his life. The Manouche were the nomadic people that had travelled and lived throughout northern France and Belgium since the 18th century living in caravans and the open air as they moved from place to place in their itinerant existence. Django was born on the road and would stay on the road most of his life as is the existence of the coveted musician, Django and Jean, two names for two lives. He would grow up living a life of impoverished freedom that would give him little formal education but enrich his life with music amongst his family and culture.

He would begin with the violin at age 8, switching to the banjo when he was 12; encamped outside the old walls of Paris, he was playing folk and Bal-musette, an early form of French instrumental music used for dances. Django played and learned from those around him; countless hours of practice and performance around the campfires and lamp lights in the caravans of his youth. He played with his brothers, his father, and uncle who were all musicians, and toured towns and villages performing for anyone who would part with a few coins for the hat. By 15, he was playing professionally scraping together enough money to survive by playing dance halls and cafés accompanying accordion players and violinists. American swing jazz had started to seep into the musical culture in Europe, threading its tendrils into the folk and traditional gypsy music that Django was already performing. The word was spreading from town to town, there was a traveling prodigy a young guitarist who was astounding audiences with his flair and talent.

In 1928 at the age of 17, three things happened to Django, and one of these would change his life forever. One: He would marry Florine “Bella” Mayer, a girl from the site he returned to outside of Paris. Two: He would make his first musical recording with the accordionist Jean Vaissade. And three: he would almost lose his life in a caravan fire; a candle accidentally into a pile of handmade celluloid flowers Django’s wife had made for a funeral that would almost become theirs. The caravan they had just begun their married life in was engulfed in flames. Florine was pregnant with their first child and they were both lucky to get away with their lives; but Django was badly burned. He was taken to hospital where the doctors told him he had received 2nd and 3rd degree burns over the lower half of his body, would have to have his leg amputated and would never play the guitar again.

Distrustful of doctors and perhaps believing more in the traditional medicine of his culture, he refused to believe the diagnoses. After his exit from the hospital, the smoke had settled and the cost had been counted, but Django couldn’t work. A promising touring opportunity had evaporated in his absence and his wife had left and gone back to her family. A dark time of the soul ensued, that perhaps many would not have found their way through. But what happened next would cast Django Reinhardt into the realms of musical folklore.

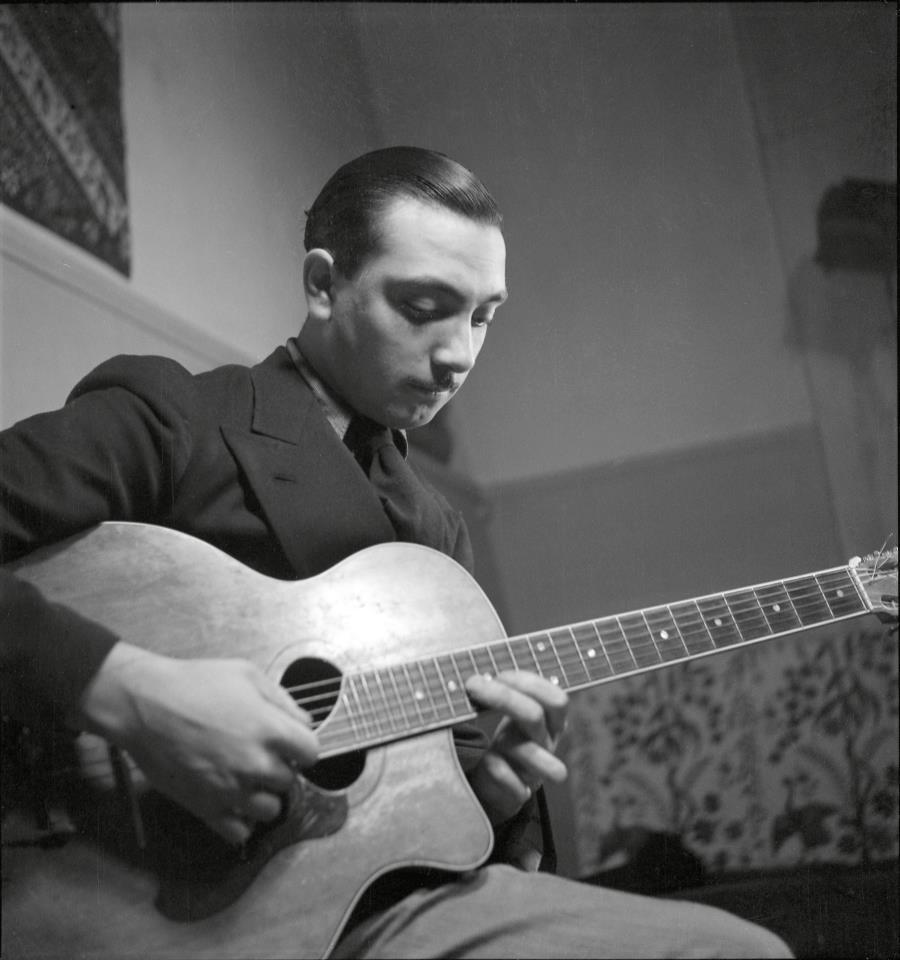

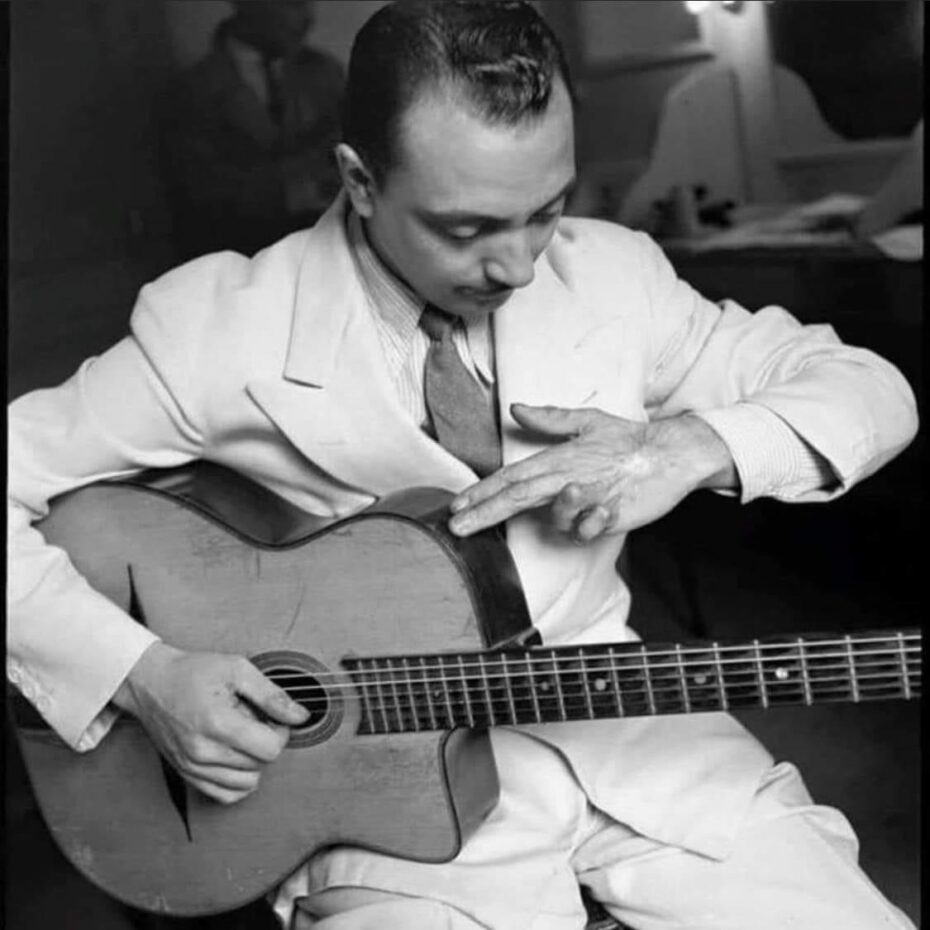

Joseph, Django’s youngest brother arrived with a new steel strung guitar, which possessed more natural amplification than the nylon or gut string folk instrument he’d used previously This meant Django could play louder using less attack from his hands. Next, Django had to develop a new way of playing using only two fingers; his left hand or his chord hand had lost the use of the little finger and his third finger. Now he had to reinvent his style as well as how the guitar was approached. He went for it, and by doing so, invented his now famous sound and technique.

He would discover new chord voicings and chordal alternations to suit his disability and with this find, his uniquely personal style and sound. It was a long road to recovery, that would have taken hours upon hours of painful relearning; something that had always felt part of him was now fighting against his touch.

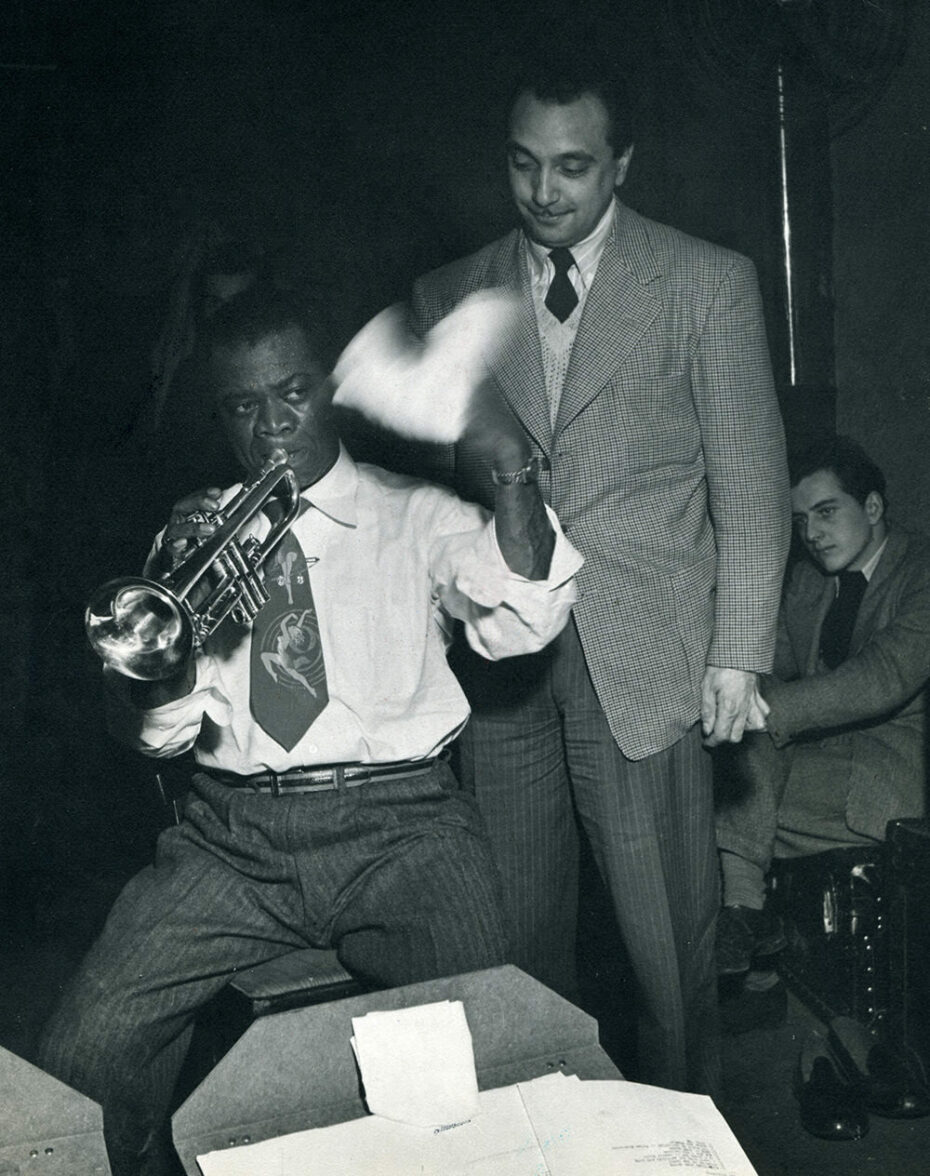

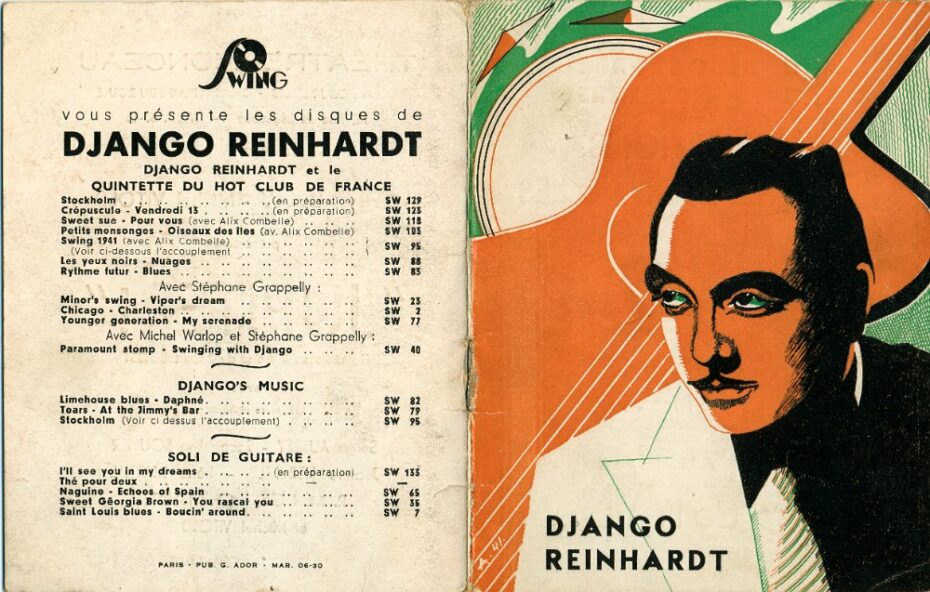

By 1931, three years after the accident, he was busking in the streets again when he was noticed by the artist Émile Savitry, who would befriend and champion the traveling musician and turn him on to the great American jazz musicians like Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington and Lonnie Johnson. Django would then meet the person, who he would he would go on to make some of the most innovative and celebrated European jazz with, the violinist Stéphane Grappelli. Together they formed the Quintette du Hot Club de France, which included Django’s brother Joseph on guitar, and bassist Louis Vola.

They had given birth to Manouche or ‘Gypsy jazz’, a variation of the music that had been born in New Orleans and now was spreading around the world as swing. Not wishing to compete with the American use of brass and reed instruments, Django and partners had developed a unique take on the new sound; their swing was made using string instruments and rhythmic nuances, and they interwove their “la pompe” strumming, decorating the sound with sweeping arpeggios.

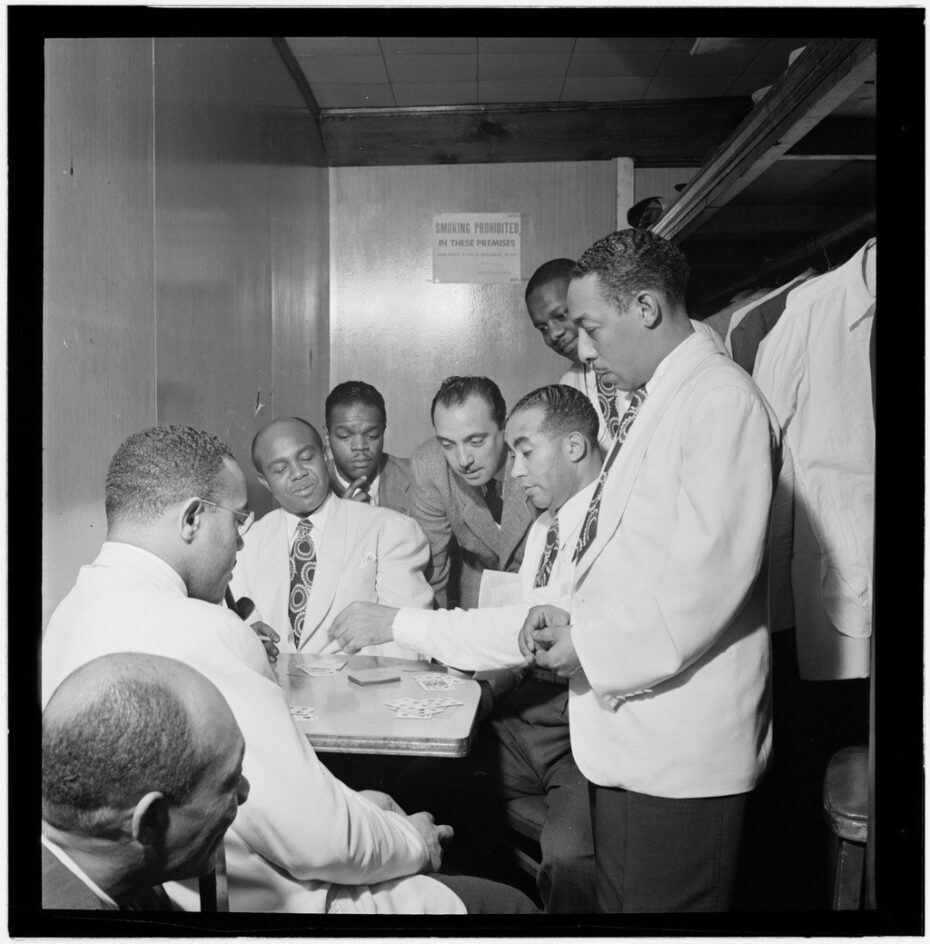

Django was free to let loose and solo with his two fingers flying up and down the fretboard of his guitar, mesmerizing all who saw it. He had mixed American jazz with his love of the music he had grown up on, and made it his own. The band would become hugely popular touring throughout Europe. Other musicians would come and go in the quartet, with Django and Grappelli remaining the core. While touring in England, World War II broke out. For centuries, the rights of the Romani people had been limited in Europe, systematically eroded; but under encroaching Nazi control, they were identified and branded with a Brown triangle, sterilized, and then herded into controlled camps. Eventually, they would be worked to death by forced labor, or sent to concentration camps to suffer the same demise as others the Nazis had declared enemies of the state.

Added to that, jazz itself had labeled as fremdländisch (alien) music by Hitler. The führer had a fear of anything that wasn’t German, let alone born from people deemed as an inferior race. Joseph Goebbels, Hitler’s propaganda minister was a little more pragmatic, he knew that jazz was wildly popular with the German people and troops alike, and that in the pressure cooker that was war, it may be better to let the people dance. When Django returned to an occupied Paris in 1939, he was at the height of his popularity, but he was going to have to play to the people who were instrumental in trying to wipe out his culture. Paris had become a playground of the Nazis when on R&R during the war and he would now have to walk a tightrope between performance and subservience, knowing that at any point they would have the power to add him and his family to a list or to have him shot. So maybe Django did play for his life and in doing so, his popularity hit its zenith. He lived lavishly, earned a fortune, spent a fortune, and made music like ‘Nuages’ that would become an unofficial French anthem for freedom and liberation. His German officer fan base tried to secure him performance dates in Berlin but Django managed to avoid ever doing so.

By 1943, Django was married again and had a son. The tide of war was turning for the Nazis and life in Paris was deteriorating, food was scarce and people were disappearing or fleeing. Django decided to try and get his family out, they fled to the Swiss border only to be caught by a German patrol. Thinking this may be the end for him and his family, he was surprised when the officer in charge turned out to be a fan and sent them all back.

A few days later, again they tried to cross the border, only to be turned away by the Swiss guards in an apparent anti ‘gypsy’ policy that saw Django and his family trapped. Miraculously they would survive the war, Django had played his way through adversity with sheer talent and a bit of luck too. Those who would have normally persecuted him, celebrated him instead.

Eventually, he would make it to America, tour with the great Duke Ellington amongst others, but would struggle with a language barrier, not just vocally but musically. Django was largely illiterate and couldn’t read sheet music. He had always made music freely from the heart, but in America, the communication breakdown left Django disappointed.

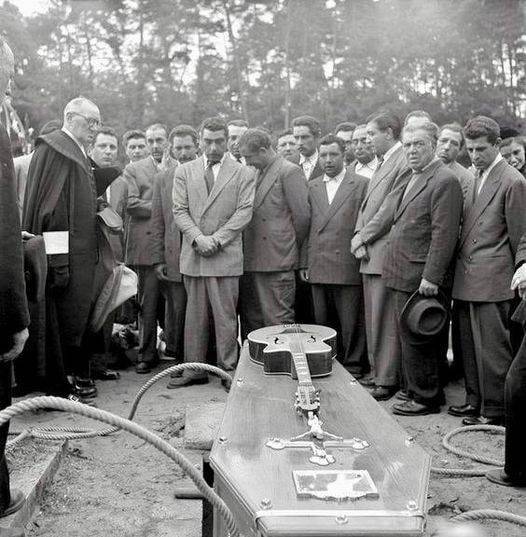

His reputation as the best jazz guitarist anyone had witnessed was coupled with his growing reputation for being unreliable. In Europe, where he was adored, he’d taken to not showing up for gigs, not showing up with his guitar, or just disappearing. Django was known to go wandering on the open road, it was something that was part of his DNA; he could not remain tied to one place. In 1953, on his way back from a performance, he suffered a brain haemorrhage and collapsed by the front door of a house in Fontainebleau that was his fixed address. He had been suffering from headaches for some time but as was his character, refused to go to the doctor. When he was eventually taken to the hospital, he was pronounced dead on arrival, he was 43.

In 1965, a 17-year-old factory worker from Birmingham, England suffered an industrial accident that took off the ends of two fingers. It was the last day of his day job before he was to start a professional career as a guitarist on tour. He was devastated after the doctors told him he would never play again, until his boss from the factory turned up with a record and told him a story. The record was Django Reinhardt’s. The injured factory worker was Tony Iommi of Black Sabbath. He would be inspired by his story and just like Django, persevered and overcame his injury to find stardom.

Django Reinhardt would fascinate and influence generations after him, from Jimi Hendrix to Jeff Beck, Willie Nelson to George Harrison. He would make over 900 recordings in his career and become a mythical figure who overcame all the odds and impairment to dazzle and astound. He lives on in jazz clubs and record collections, around campfires, and in the music of his descendants who continue to keep what he created alive today.