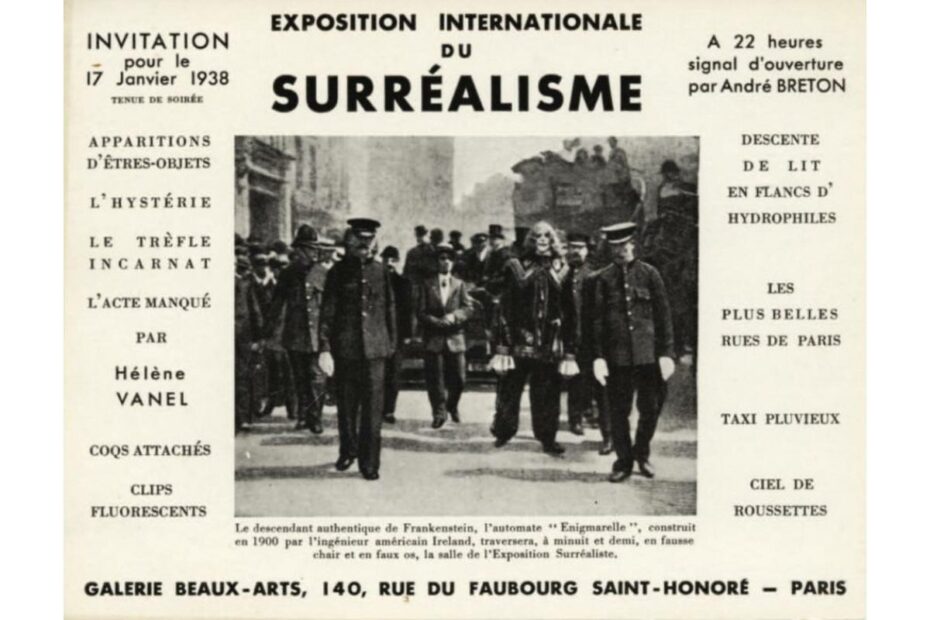

The 30’s was a booming, sensational time for the bizarre and avant garde – a high time for the flashing waves of surrealism before the dawn of the Second World War. Dali and Miro were still painting, Duchamp was on the scene, and Man Ray was producing photographs like the world had never seen before. It was cool to break free from the rules of classical art and everyone who was anyone was ready to pull out their purses to pay and see it. In 1938, the exhibition of all exhibitions showcased the most fabulously obscene and interactive collections of surrealist works under one roof in Paris. For the first time.

Andre Breton and Paul Eluard, the fathers of the movement, had decided that the public needed not just another surrealist exhibition but an all encompassing surrealist environment. Paris needed a place to be engulfed in the vision of the uncouth and crazed vision of the artist. Max Ernst once said that surrealism is meant to be a combination of elements which appear alien together and that when these seemingly distant products, images, or whatever else come together, can “provoke the highest poetical lighting.”

So imagine, the vision curated and created by two great surrealist writers, Duchamp as official referee between the two, Max Ersnt and Dali as overseers and advisors for technical business, Man Ray on lighting and photography, and Wolfgang Paalen on design of the entrance and the “grotto womb” which we’ll get to later.

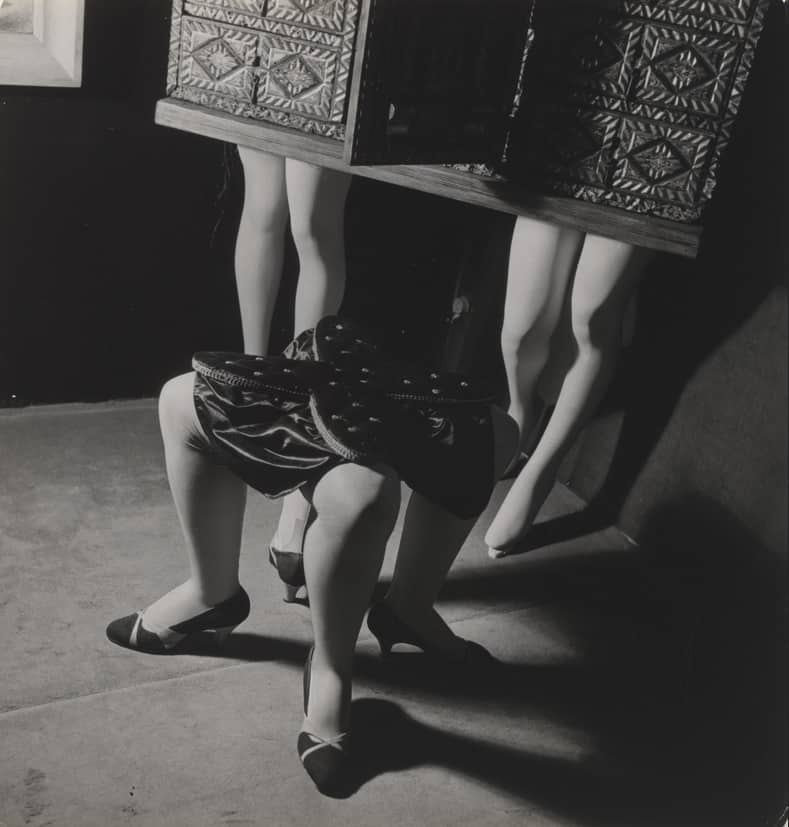

So let’s take a journey in our time machine there, shall we? 229 individual works by 60 artists from 14 countries were shrouded in the bizarre all-embracing environment. Imagine live actors jumping from pillow piles, performing breakdowns and writhing on the floor. Mannequins dressed to elicit lust, decorated in cages, and lace, humanoids and human limbs in place of proper furniture leggage.

L’exposition Internationale du Surrealisme was split into three parts, Taxi Pluvieux (rainy taxis), Plus Belles Rues de Paris (the most beautiful streets of Paris), and the third space, which was akin to a womb. When we enter la Galerie des Beaux-Arts, we are met with Dali’s rainy black taxi where the driver’s head is in the mouth of a shark mask. He’s wearing sunglasses and the woman in the back is adorned with live snails and lettuce. The vehicle is systematically assaulted with water to provide the viewer with the impression that there is perpetual disarray and discomfort – perhaps a way to tingle the senses – but who knows about Dali’s true intentions. The woman is in an evening dress and her blond wig becomes disheveled as the night progresses.

Le Plus Belles Rues de Paris were an homage to beloved people and places of the founding artists of Surrealism. Rue de la Vielle Lanterne, a street of Paris’s past, was commemorated here, both as a favorite place and the scene of the great poet Gerard Nerval’s death (you might remember him for taking his lobster on a walk around Paris and hanging out with the Bouzingos).

They also paid their respects to the young poet Comte de Lautréamont (the nom de plume of Isidore Lucien Ducasse). Ducasse died at the age of 24 but is said to be a founding inspiration for the movement itself. The hall included a post for rue Vivienne, as Lautremont lived and worked there for some time at the end of his short life. Rue Nicolas Flamel, which was both a real street and obsession for many poets within the movement was placed in the exhibit as well. The fable of the medieval subject, Flamel, and his hand in creating/ discovering the “philosopher’s stone” had been a topic covered in many a surrealist poem. Other fictional streets included rue de la Transfusion de Sang (blood transfusion road) and rue de Tous les Diables (Street of all the devils).

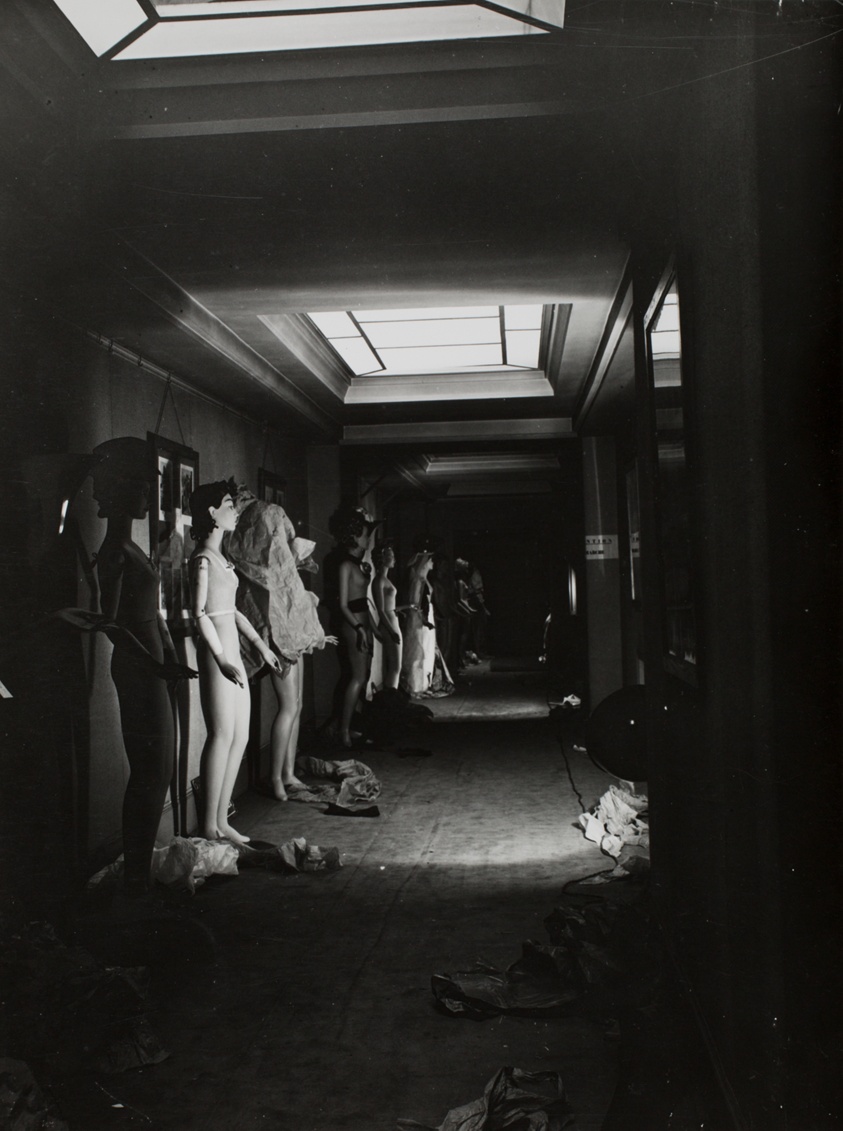

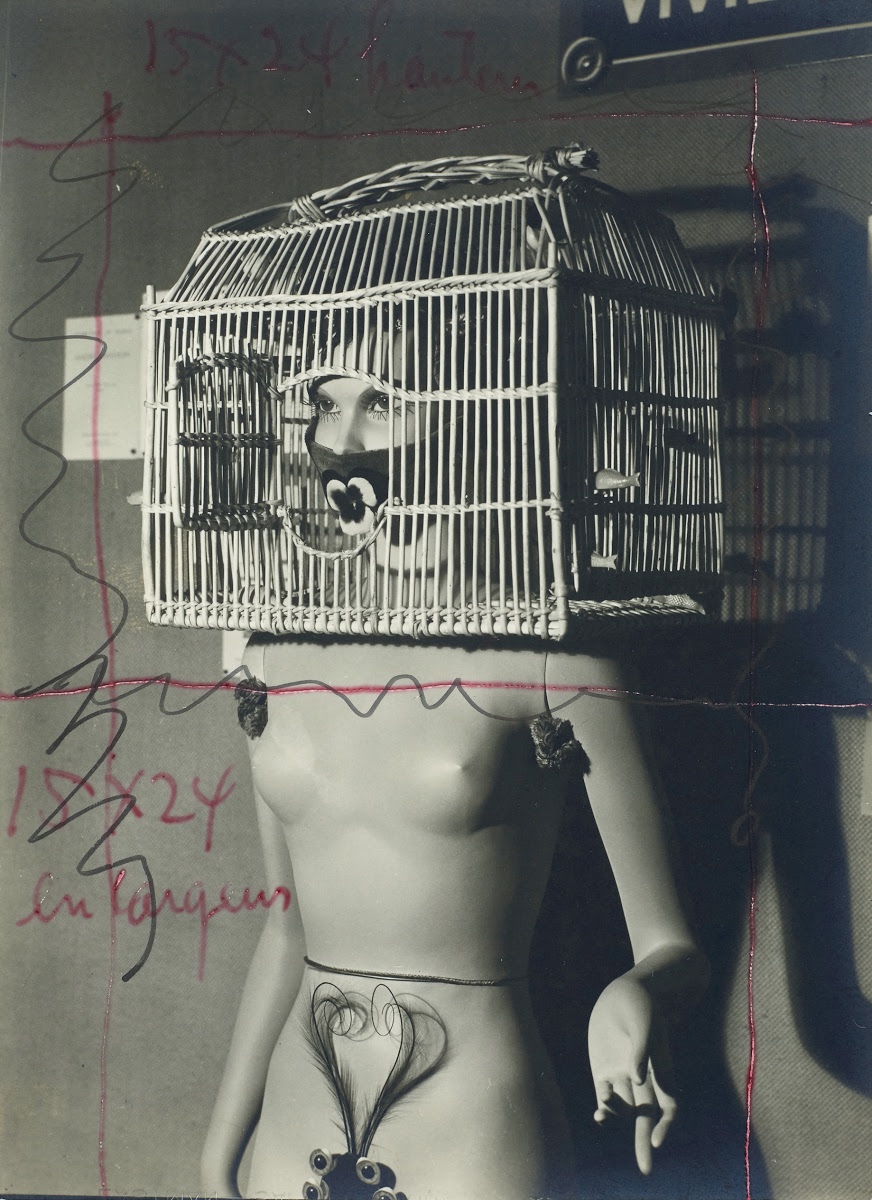

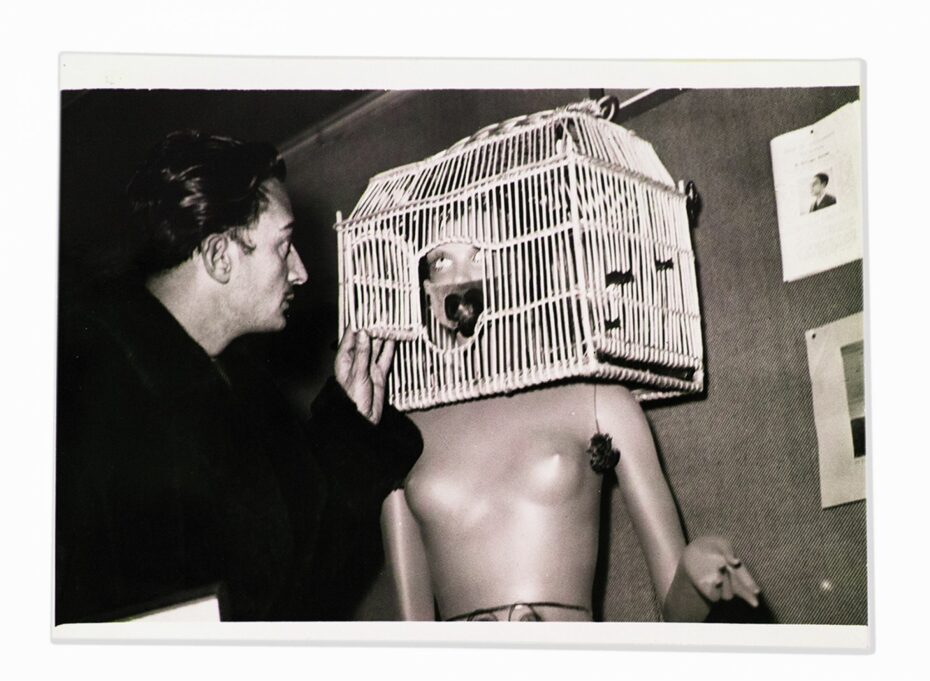

These street corners, both real and otherwise, were lined with 20 or so decorated mannequins. Perhaps these figures were a shout to the sex workers of the day as they alluded to sex, sometimes femininity, and some might even say control. Photographs of André Masson’s mannequin show a naked body with a bejeweled crotch wand feathers sprouting towards the navel in the shape of a heart. The figure’s head is adorned with a bird cage and the mouth is decorated but gagged and covered with a flower. Audrey Hepburn would show up to a famous Rothschild Surrealist-themed ball in 1972 dressed as this mannequin.

Another, by Oscar Domínguez, was draped in only a white sweeping fabric and rope which coiled neatly up one arm and around a pole next to it. The eyes are obscured by a pyramid shaped crown.

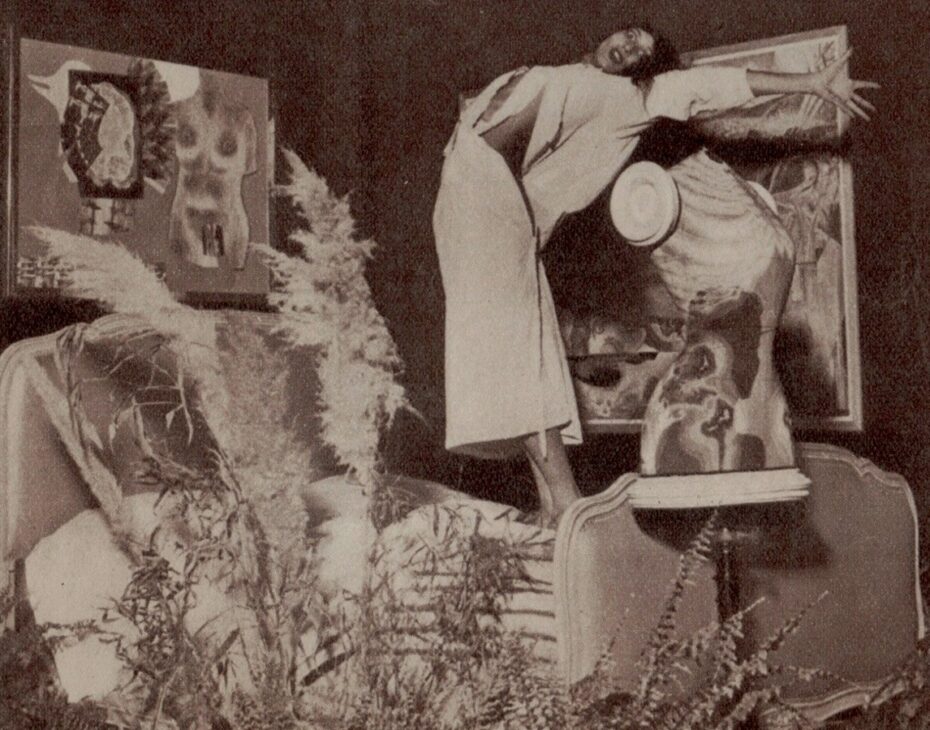

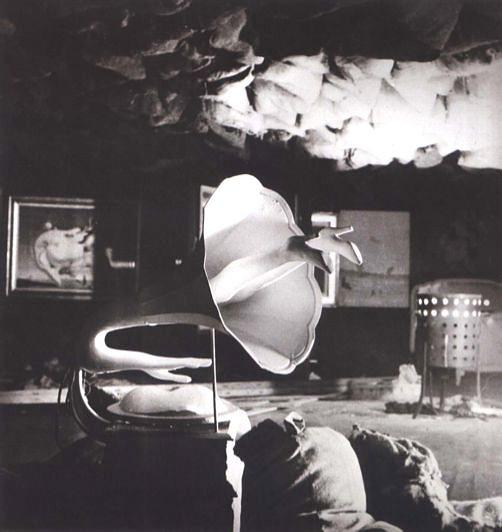

Once past the most beautiful streets of Paris and the figures which lined them, the guests were welcomed into the main room – the grotto. Imagine that as you’re about to step inside, you’re handed a flashlight (Man Ray’s lighting failed for the opening night), and you step inside a damp room. The floor is wet and muddy. Guests shuffled through the leaves brought in from the Montparnasse cemetery. The air smells faintly dusty from emptied coal sacks on the ceiling, creating the illusion and sensation of an industrially manufactured cave. Paalen’s “Avant la Mare,” (Before the Mother), is a pond with water lilies, evoking a dark and primordial experience. Actress Helen Vanel was trained by Ernst, Paalen, and Dali to act out a scene of hysteria in this room, thrashing and screaming, and splashing “madly” through the pond.

The accidental darkness, paired with the hysterics of the actress, were taken to varied interpretations – some of which believe was a precursor and comment on the change of the artistic movement in the face of political change and conflict of the looming war. Others have concluded it was more likely a comment on the hardships of being a human through complicated relationships and emotion.

The point of the main room, at least on opening night, may have been missed. Surrealism was a big ticket item and exciting to the people who lived during the time of the movement as it is for us today. Evening dress attire was required for the visitors for the opening. Man Ray, disappointed, and rightfully so, recounted after the fact that it was “unnecessary to mention that the flashlights were pointed at the faces of the people rather than at the artworks themselves. As at every overcrowded vernissage, everyone wanted to know who else was around.” But even with the lights out, the show was a success.

Three thousand people poured into les Beaux Arts for the night of January 17th and nearly 500 people came to see the exhibit daily through the end of February. Loved and hated by the critics, as all art is, the show was seen perhaps less for what it was truly meant to represent and more or less as an elaborate joke. However, as the years have passed and future generations are able to see what this collaboration has been able to change for the art world, especially in a time brinking on major tumult and tension. We are able to see how burgeoning tensions on a global scale create a radical need for the unexplainable and for something new, something stimulating. Maybe it’s time for surrealism of this scale to make a come back…