There are many reasons to tell the story of Mata Hari – an extravagant icon of femininity, famous burlesque performer, World War I spy, and “collector” of high one standing lovers – her life reads like a harlequin novel. But arguably one of the most curious (and morbid) anecdotes of her life occurred after her death (by execution, no less). As if her missing severed head wasn’t enough to lead with, it has also come to light that the rest of her body, which was entrusted to the Museum of Anatomy in Paris, also disappeared from the archives. So what happened to Mata Hari?

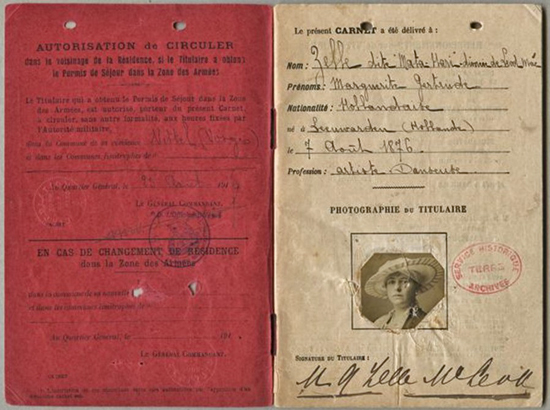

She was born as Margaretha Geertruida Zelle in 1876 in a town called Leeuwarden in the Dutch province of Friesland. The daughter of a successful hat merchant, Margaretha lived a very comfortable life until her father’s business went bankrupt and he left his family in the lurch. Two years later, her mother passed away, and Margraretha and her siblings then went to live with an uncle and aunt.

Margaretha’s uncle envisioned a very decent life for the 14-year old and sent her off to the Dutch city of Leiden, to be trained as a kindergarten teacher. But the young Margaretha had other things on her mind. She began flirting with the school principal – and was ultimately caught topless on his lap. Her career as a kindergarten teacher was nipped in the bud there and then, and she was sent away (again) to live with another uncle in The Hague.

At the age of 18, Margaretha came across an advertisement by Dutch Colonial Army Captain, who was looking for a “girl of sweet character with the intention of marriage.” She responded to the ad, sending along a very enticing picture of herself. Despite a 21-year age difference, she married Army Captain Rudolf MacLeod on July 17, 1895.

The marriage brought Margaretha back into Dutch circles of high society and secured her a wealthy lifestyle, but it was an unhappy marriage. McLeod was a heavy drinker, and not amused by the attention she got from other men. A few years into their marriage, the couple moved to Java in the Dutch Indies, where they had two children: a boy, Norman, and a girl, Jeanne-Louise. Their son died in 1899 (there are several theories that he was poisoned by a maid) putting additional tension on the marriage. The couple separated in 1902.

After her divorce, Margaretha moved back to the Netherlands, leaving her daughter Jeane-Louise to live with her father. Never receiving the promised alimony, Margaretha decided to make a fresh start in Paris. Drawing on dancing lessons she had taken during her time in the Dutch Indies, she started out as an exotic dancer and courtesan (prostitute for the higher classes). She made her official debut at Guimet’s theater in 1905 and adopted a new exotic name: Mata Hari, which means “Eye of the Dawn” in Malaysian.

By the age of 29, Mata Hari had become a riveting sensation in Paris and abroad, performing in all the major cities of Europe. She was a master marketer of her own act and promoted herself as a performer born and trained in Java, creating a more and more elaborate backstory for herself as her career developed.

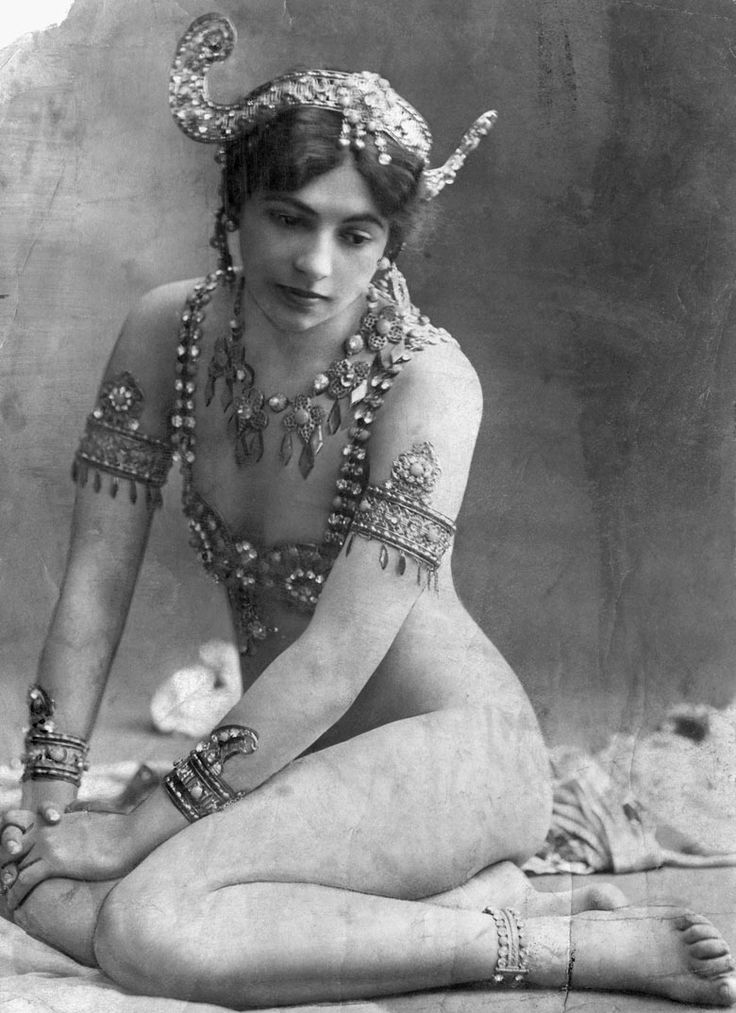

The papers wouldn’t stop raving about her burlesque performances, in which she slowly removed items of clothing, revealing intricately-made undergarments. In one famous performance, she even came out onto the stage naked on a white horse.

Mata Hari is often described as not having being a “standard beauty”, but magnetically attractive nonetheless; “slender and tall with the flexible grace of a wild animal, and with blue-black hair”. An Austrian reporter said she made “a strange foreign impression.” Another reporter wrote that she was “so feline, extremely feminine, majestically tragic, the thousand curves and movements of her body trembling in a thousand rhythms.”

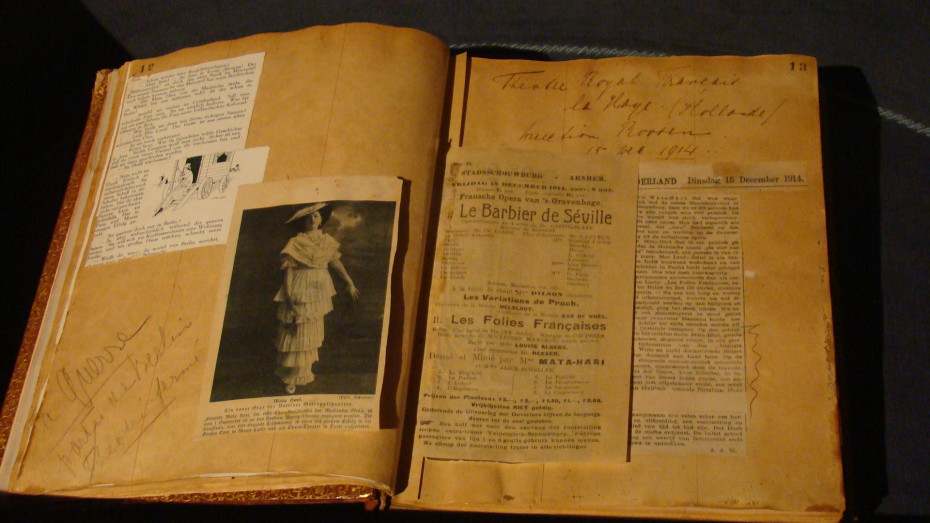

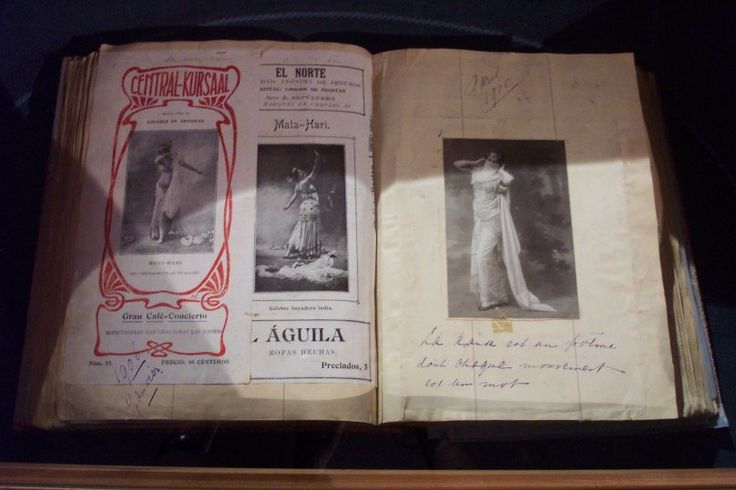

Mata Hari was confident in her sexuality and had a weakness for wealthy men, preferably in uniform. During her ten-year career as a dancer and courtesan, she had countless affairs with men of all nationalities and backgrounds. Her lovers include baron Henri de Rothschild, composers Massanet and Puccini, and chocolate factory owner Gaston Menier. She kept notes and memorabilia of her performances, affairs, and lovers in two large scrapbooks, bound in calfskin, with her name written on them in golden letters, which she carried around with her on her travels. (These are now in the care of the Frisian Museum and available for viewing online).

Mata Hari’s position as someone who had intimate contact with many international officials did not go unnoticed. As tensions between European countries intensified at the advent of World War I, she became an interesting potential player on the stage of international espionage. Mata Hari’s role as an international spy is still contested, but many believe she was indeed recruited and active as a spy at the start of WW I.

Mata Hari’s Passport – (C) Ministère de la Défense

In 1916, she presumably got involved with the German intelligence service, which gave her the codename of “Spy H21”. They offered her an advance pay of 20,000 francs, which she took to Paris. There, she fell head over heels in love with a Russian army officer. Shortly after, she was asked by the French intelligence service to do espionage work for them. Never one to be overtly cautious in her life choices, she began working as a double agent. This decision eventually led to her tragic death – both the French and German intelligence services mistrusted her motives and she was arrested in France on charges of high treason.

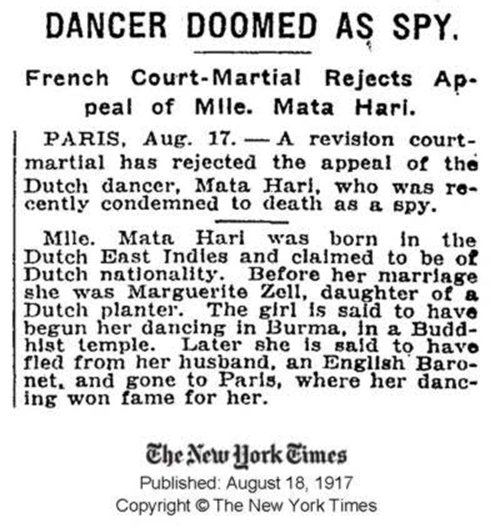

The Netherlands tried to get her reprieve, unfortunately to no avail. She was executed by a firing squad in 1917 at the age of 41 in the woods surrounding Paris, seven months after her arrest. There is no incriminating proof however, that Mata Hari ever worked as a double spy. This all remains largely a mystery, not helped by the fact that her sealed trial and other related documents, a total of 1,275 pages, were kept classified by the French Army until as recently at 2017, one hundred years after her execution.

It’s not entirely clear how her head became separated from her body, but according to an eyewitness, a British reporter Henry Wales, she defiantly blew a kiss to the soldiers before they fired. Wales wrote that after the volley of shots rang out, “Slowly, inertly, she settled to her knees, her head up always, and without the slightest change of expression on her face. For the fraction of a second it seemed she tottered there, on her knees, gazing directly at those who had taken her life. Then she fell backward, bending at the waist, with her legs doubled up beneath her.”

Hari’s body was never claimed by any relatives and was subsequently donated for medical study – which might explain how her head was removed. The Museum of Anatomy embalmed her head and and it was “kept” there until – well, until archivists realised over 80 years later in 2000, that it had disappeared. It’s possible that the head went missing as early as 1954 when the museum relocated. Somewhere out there in someone’s macabre curiosity cabinet, Mata Hari’s head might very well be sitting on a shelf. Despite a record from 1918 confirming that the museum was also in possession of her body, the rest of Mata couldn’t be accounted for either by archivists.

The riveting story and legend of Mata Hari lived on however. Fourteen years after her death, in 1931, American production company MGM bought the rights to her life story and produced a movie based on Mata Hari’s life starring Greta Garbo.

She’s a historical figure still wrapped in mystery and it seems almost impossible to truly unravel her story. But seeing as Mata Hari knew the power of a little mystery all too well, she might appreciate the fact that people are still trying to figure her out, inspired by her story and mystique along the way.