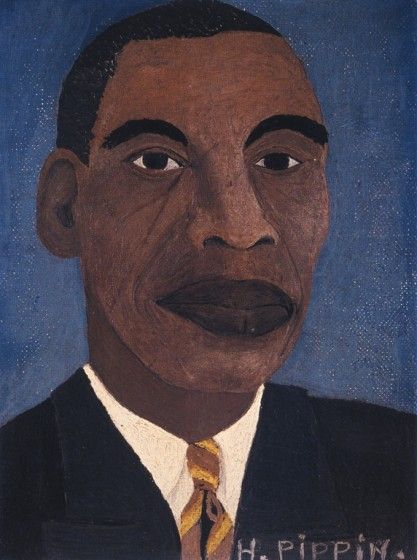

Horace Pippin was an artist who was gifted with the ability to express his work with an unrefined social realism and dreamlike playfulness of touch that in reality, would mask a darker narrative. The grandson of African American slaves and a decorated World War One veteran who was registered as disabled after being wounded in France in 1918, Pippin sought to express life through his painting, a life of hardship, of war and loss, segregation and belief.

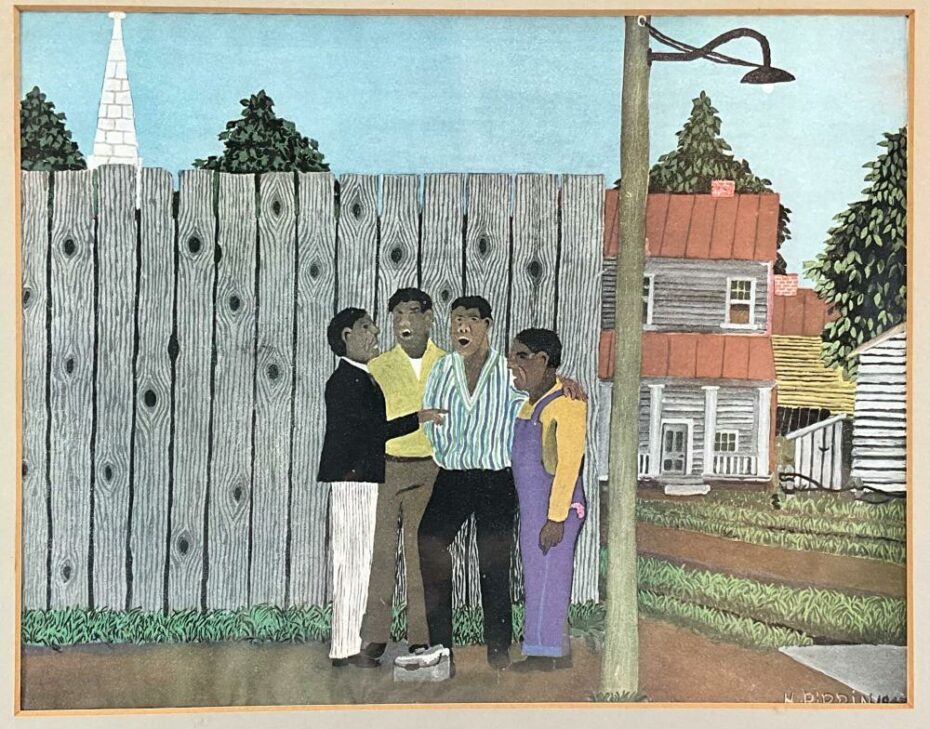

Pippin was a self-taught painter, which would put him in the bracket of an ‘outsider artist’ by some critics, a classification that the art world adopted to bestow on anyone out of their field of social and cultural vision of how an artist should have developed. When he was finally discovered during the Harlem Renaissance movement in the 1920s, he would be labeled as a ‘primitive’ and ‘folk’ artist, but today he is celebrated as an important figure in the development and historical reportage of African American culture of the 20th century.

Born in Pennsylvania in 1888, Horace Pippin grew up in Orange County in New York State. His parents were cast into a life of servitude as domestic workers. As a young boy, he began attempting to express himself through drawing and mark-making with any material he could find, his family being too poor to purchase art supplies. At 10, he won a local drawing competition that rewarded him with the much-coveted art material so he could pursue his passion further, though only for a short time as he was expected to begin work at 14 to help support his family. When Pippin found employment in factories and coal yards, as an ironmonger and a porter, the distant rumblings of World War I began to sound in Europe. America declared its entry in 1917, and over twenty thousand African Americans enlisted in the hope of being recognised as full citizens or escaping the segregation and Jim Crow laws at home.

Pippin was one of the many who signed up to fight when he was 29. Assigned to the 369th Infantry Regiment, initially the Black GI’s were only deployed as labourers and support units until shortages on the front line propelled them into the fight. The 369th infantry would be attached to the French army and became known as the famous “Harlem Hellfighters” for their bravery and valour. They were also awarded the French Croix de Guerre medal for bravery, suffering the most casualties of any other American regiment having spend the longest amount of time on the front line. Pippin would be amongst the wounded. In 1918, during an advance the enemy lines, he was shot three times by a German sniper. The first two were flesh wounds, the third split his shoulder blade in half and wrecked the joint. He was honourably discharged in 1919 and returned to the United States where he was entitled to a meagre disability pension of $22.50 per month.

Pippin struggled to find regular work, but augmented his pension with a variety of jobs; scrap dealer, labourer, truck driver. Injured veterans were expected to become professional cripples, to panhandle for change, in a time before rehabilitation became an important army protocol for its wounded soldiers.

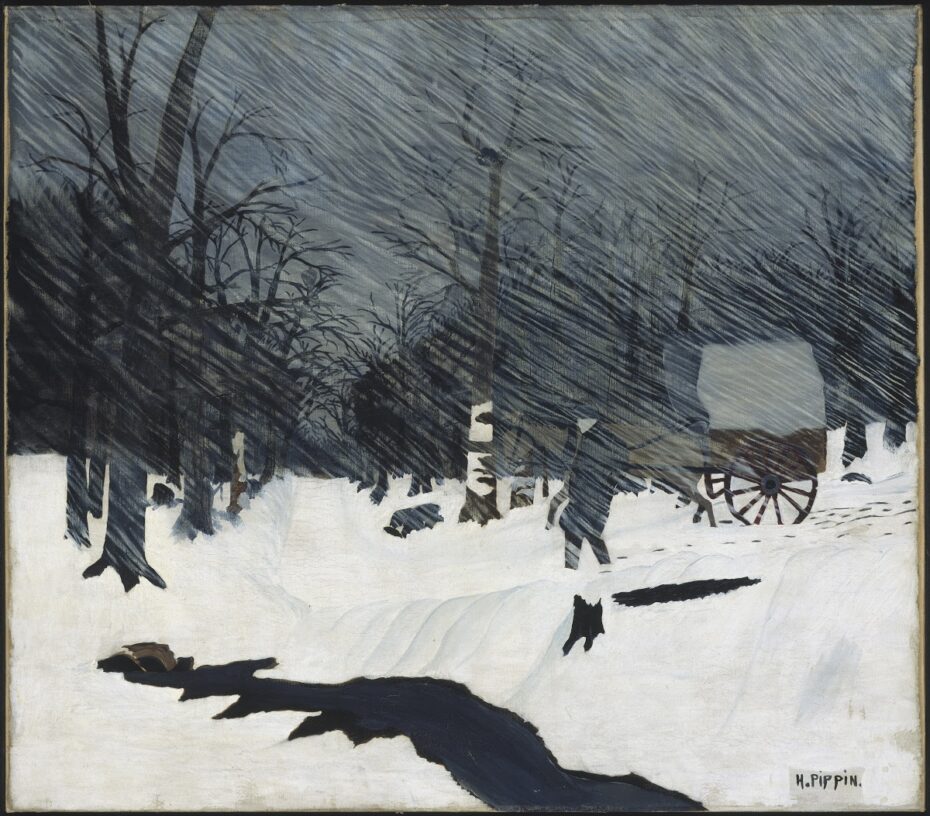

In the 1920’s, Horace married and moved back to Pennsylvania where he began to explore his shrouded creativity. He had something to express, something to share and communicate through his art, a cathartic expression of circumstance, which he now turned loose. His foray into creativity began with Pyrography; he would burn images onto wood panels and add paint. A tentative beginning and an almost physical expression linked with conflict and destruction. His first full canvas “Starting Home” (1931–34) dealt with his wartime experiences, a dark violent rebuke of war and its aftermath.

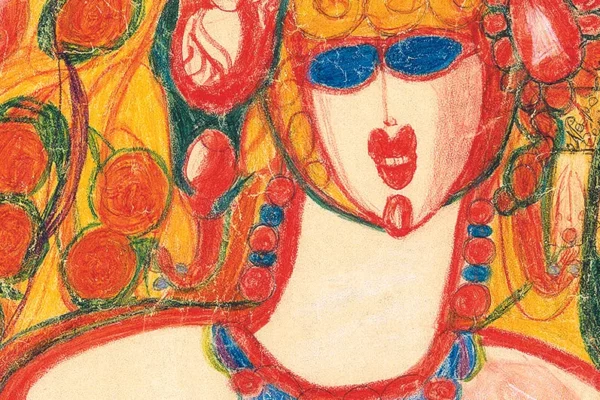

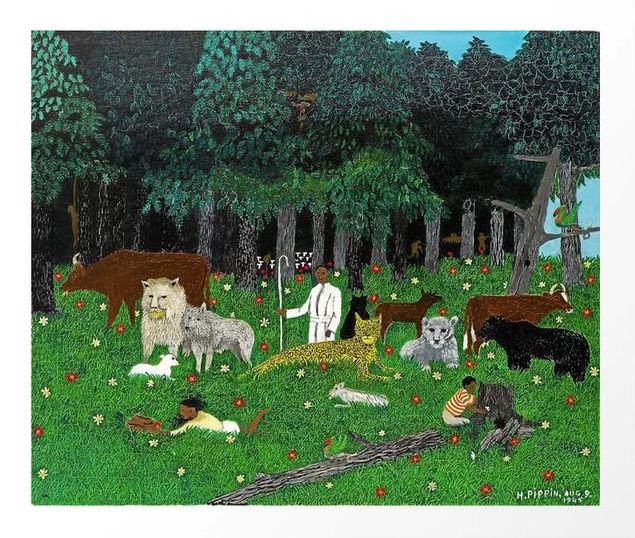

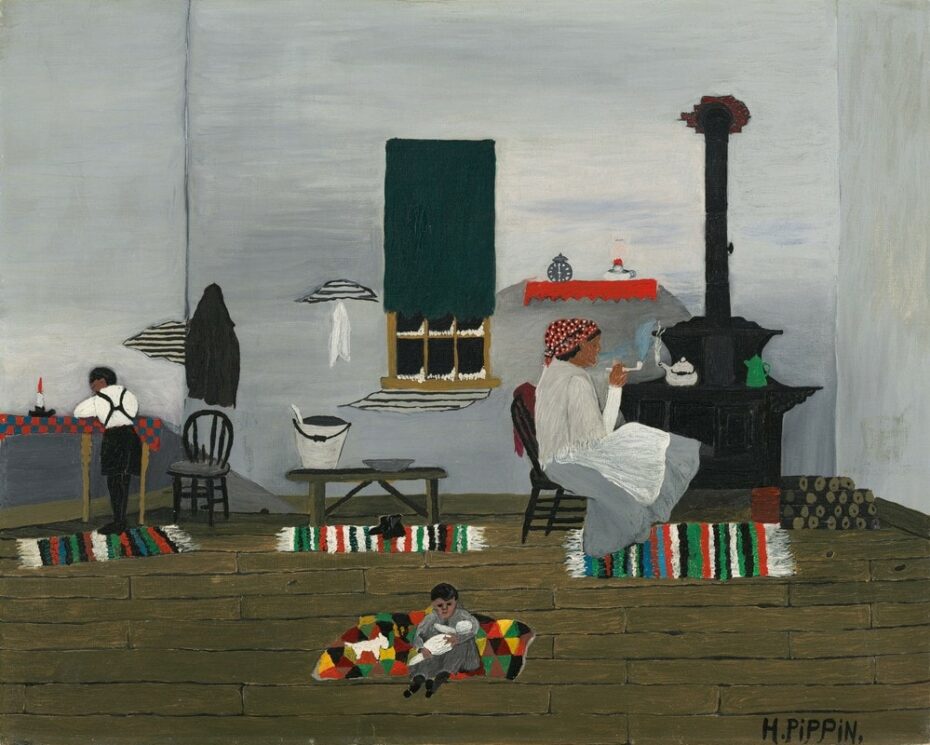

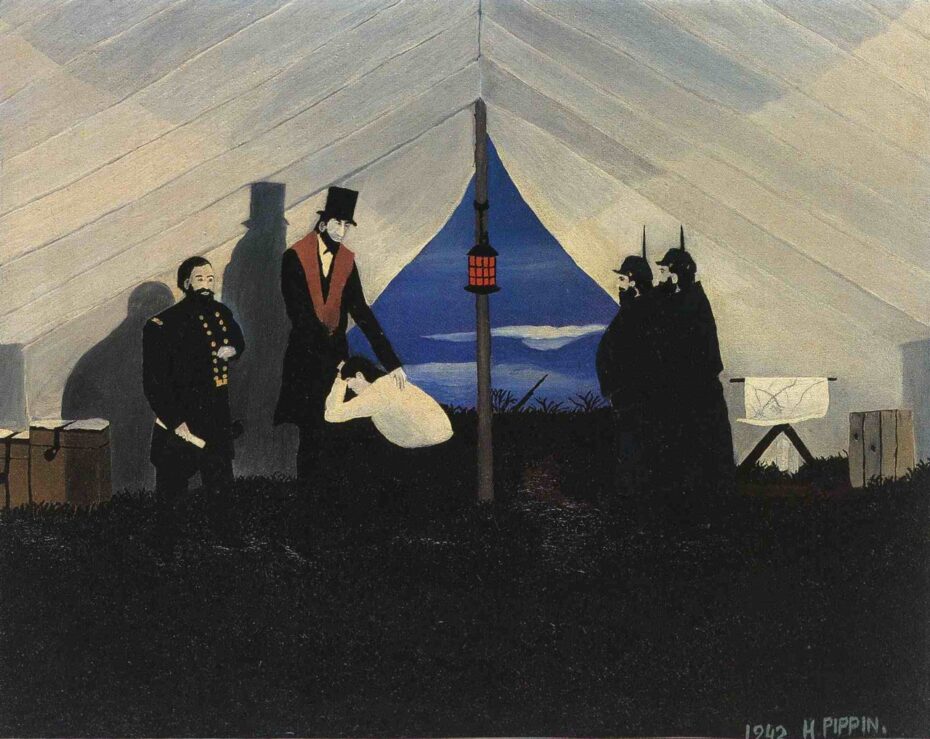

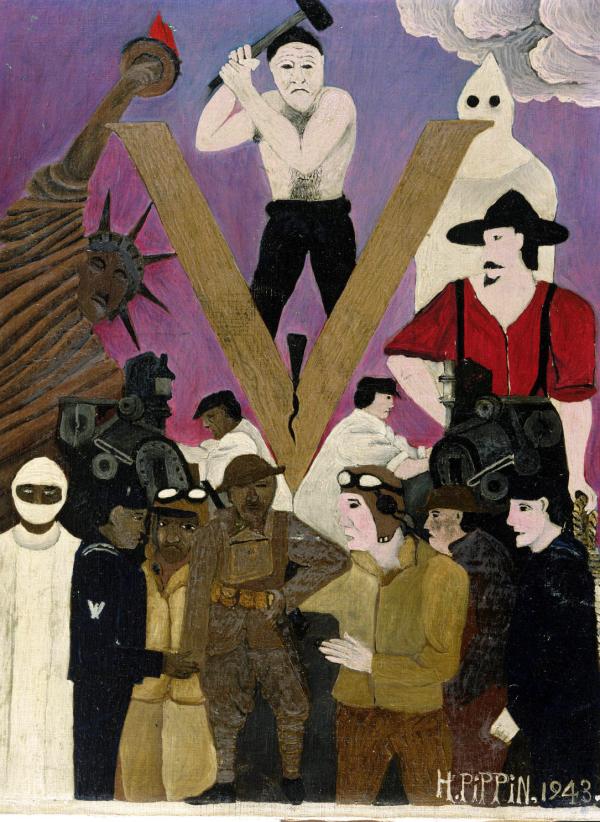

Pippin would explore religion, war, the human condition, and his own. His paintings held a quality of linear progression and a vivid palette, where blocks of colour interact with scenes of a figurative display. Biblical stories sit in juxtaposition next to visions of war and racial discrimination, domestic scenes, and self-portraits. Mr. Prejudice (1943) inquires what if anything has changed for African Americans with the victory and sacrifice of war.

In 1937, during a period of interest in what would be described as ‘folk art’ or the ‘Harlem Renaissance’, Horace Pippin’s work would be discovered in a local art exhibition for the Chester County Art Association, which he had been encouraged to enter. From this first showing, a solo exhibition was organised, which led attention of the Museum of Modern Art and the inclusion in the traveling exhibition: “Masters of Popular Painting”.

Pippin had arrived in the art world at a time when ‘cultural expression’ was popular. Advocates like Alfred H. Barr, Jr., art historian and the first director of the Museum of Modern Art, and art curator Dorothy Canning Miller would be pivotal in Pippin’s career and other artists’ work being seen and appreciated. Exhibitions would be held all across the United States and Europe. Pippins’s work would be featured in Vogue, Time, and Life magazines, but his success came relatively late in life. Personal tragedy marred his final years; his wife was institutionalised after a mental breakdown and Pippin was set adrift alone into the unknown waters of attention and fame. He died in 1946 at age 58.

Horace Pippins’s legacy is of art and hardship and the act of creativity to oppose repressive forces and heal trauma. His injury left him with only partial use in the arm he painted with. Walking through the fire of war and the realities of life at home had burnt its relief into the soul and oeuvre of an artist who is celebrated as a true realist.

“I can never forget suffering and I will never forget sunset. I came home with all of it in my mind.”

Horace Pippin