James Hampton’s magnum opus was discovered posthumously in a rented garage he had converted into his studio. The installation features over 180 individual found objects, mostly collected from dumpsters on his way home in the early hours after midnight, when he would clock out from his janitor duties at the GSA in Washington DC. The monumental installation, adorned with shimmering foil and various other discarded materials, offers a poignant glimpse into the mystical and mysterious world of a self-taught artist and deeply private individual.

Critics and scholars have debated whether Hampton’s extraordinary artwork titled “The Throne of the Third Heaven of the Nations’ Millennium General Assembly,” was intended for a public audience or if it was a personal sanctuary meant only for himself—or perhaps for a divine spectator. Discovered quite serendipitously after his death in 1964, Hampton had been renting a garage in a Washington, D.C., alley that he used as his studio. The landlord, who was unaware of the contents, entered the garage and found the expansive artwork.

The discovery was a complete surprise to the few that knew him. Hampton, a reclusive individual, who had never married and lived in a small apartment alone, had not shared his work with others. His surviving family were not interested in claiming the artwork, so the landlord put it up for sale in a local newspaper. Luckily, an artist saw the ad and came to see it for himself, instantly recognising the potential significance of the find and had the good sense to contact a friend who worked at the Smithsonian Institution. Harry Lowe arrived at the garage, and later told the Washington Post that “it was like opening Tut’s tomb.”

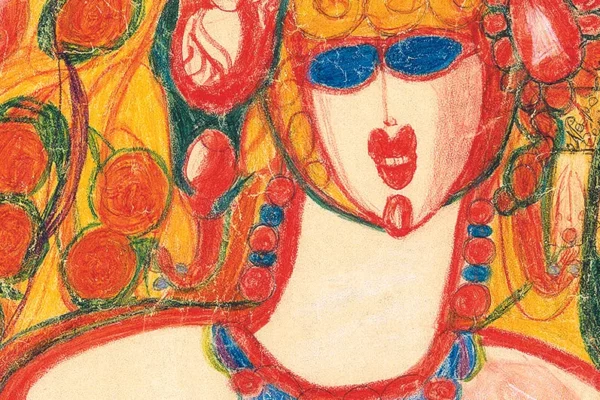

Since its discovery, Hampton’s Throne has been housed at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. It stands as a seminal piece of American folk art and “outsider” art. The centerpiece is a throne-like chair flanked by altars and other religious iconography, reflecting a complex spiritual vision. He crafted an otherworldly space using aluminum and gold foil, light bulbs, and glass, and his technique involved layering and arranging materials to create a shimmering divine effect.

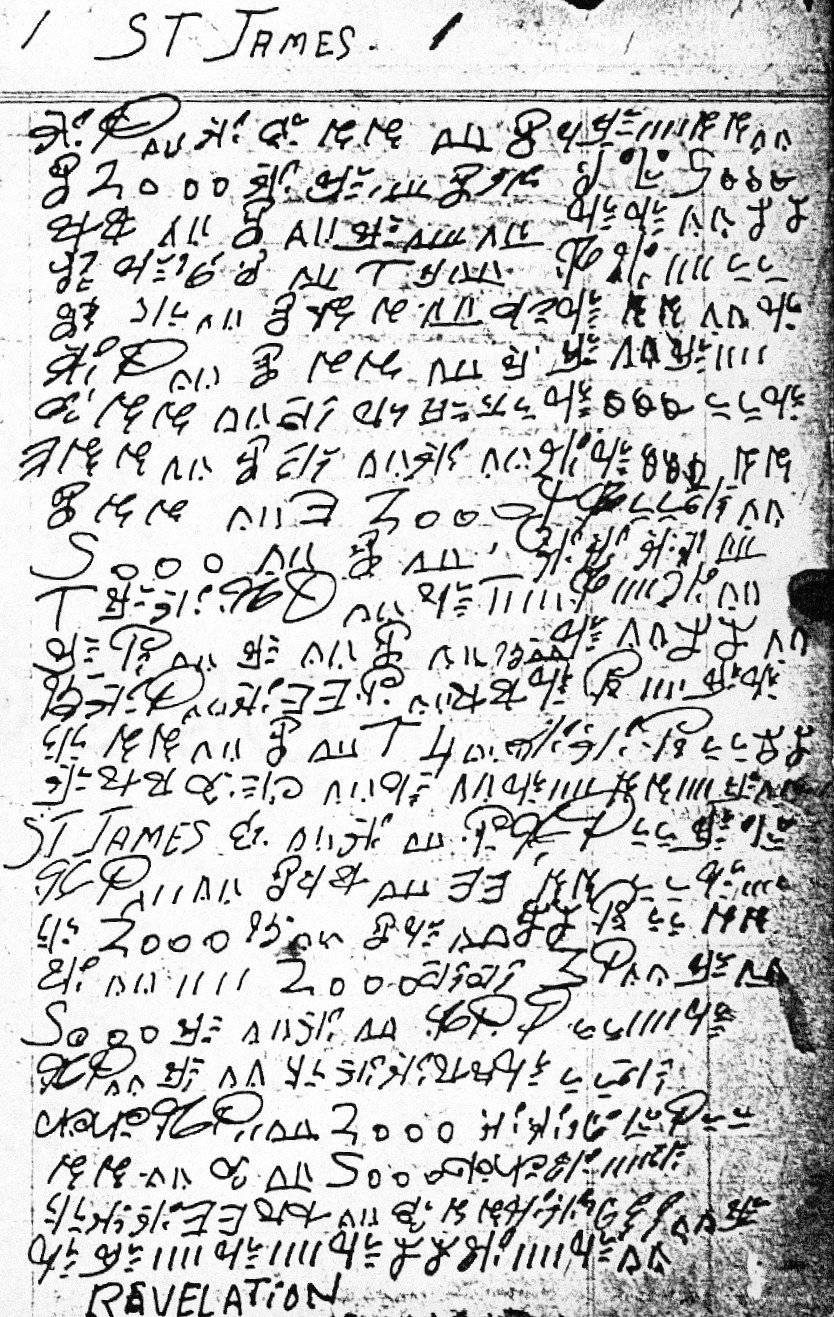

James had also left behind notebooks and binders written in an indecipherable code, recording his visions. The text that accompanied his work, still to this day not been deciphered. The use of secret languages and cryptic symbols is not unusual among visionaries and Hampton may have considered himself a latter-day prophet. Perhaps something from another world did visit James Hampton, but whether they were angels or aliens, it is unlikely that even he could say.

The notebook has been scanned and is available to view online here.

What is known Hampton’s life outside of his secret masterpiece, is pretty standard in comparison. He was born in Elloree, South Carolina, in 1909. After his mother’s death during his childhood, he moved to Washington, D.C., where he lived with his older brother. His life was marked by simplicity and solitude, including a stint in the U.S. Air Force during World War II. After his service, he worked as a janitor for the General Services Administration in Washington, D.C., a job he held until his death in 1964.

James Hampton’s work remains a significant yet mysterious landmark in American art. An untrained artist working in isolation, his legacy continues to inspire and mystify, a testament to the power of art to transcend the ordinary and illuminate the extraordinary. And it wouldn’t be the last time a janitor would shock the art world with his secret life.