The Palace of Versailles, famously opulent and vast, is often celebrated for its architectural grandeur and the lavish ceremonies that took place within its walls. But at its core, it was essentially a giant overcrowded hotel of horrors for the entire French nobility, who were given their own room and key that symbolised both privilege and entrapment. Beneath the gilded surface, Versailles was not merely a royal residence but a sophisticated mechanism of political control, designed to keep the French nobility on a tight leash and under close surveillance. One might even compare it to the Bates motel. Cloaked in the guise of “luxury” hospitality, it was however, a masterclass in political strategy.

So how would Hotel Versailles fare in the ratings? Not very well at all. Think more “roach motel”. The palace was very crowded, and residents were typically allocated small rooms, not based on payment but on loyalty and status. Garret (attic) rooms were all that was left for the aspiring courtier, which were basically ultra-cramped, unsanitary, and sparsely furnished (if at all).

But it wasn’t just the aspiring nobility that drew the short straws. Versailles famously didn’t have toilets. Only the most high-ranking favourites of the Sun King had private closets in their rooms, but the first flush toilet wasn’t actually installed until the next king, Louis XV came to the throne. Even Marie Antoinette was said to have been once hit by a chamber pot being emptied out of a window. There were very limited public latrines available on the estate, and they would have made the toilet cubicles at music festivals look like the Four Seasons. They often overflowed from overuse and sewage seeped into the apartments of Versailles. Courtiers and servants alike took to relieving themselves in the palace, crouched down in the corridor or curled up in a window recess. One German Princess Elizabeth Charlotte staying at Versailles remarked, “the people stationed in the galleries in front of our room piss in all the corners. It is impossible to leave one’s apartments without seeing somebody pissing.”

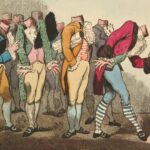

To avoid the foul odours of Versailles, courtiers would douse themselves and even bathe in perfume, which only added to the stench. The most glaring problem was that the palace was too crowded, housing not just the extended royal family but all State bureaucrats – ministers, vice-ministers, judges, generals, admirals, ambassadors, clergymen, as well as their families and servants that came with them – all under one roof!

There was little choice in the matter. Nobles who wanted to be close to participate in court life had to maintain residences in Versailles; a veritable gilded cage. Nobles were relocated from their power bases in the provinces to the palace, distancing them from their lands and people and reducing their ability to muster local power or plot against the monarchy. A duke who might have been used to living in luxury at his own palace with his own servants, would suddenly find himself living in a cramped and filthy Versailles hotel room with no toilet.

While the less-than-desirable living quarters one received were technically provided at the Crown’s expense, the financial obligations associated with maintaining a presence at court could be significant. The complex system of etiquette and court life at Versailles required nobles to dress in expensive clothing (or face a social death), give gifts to the king and other nobles. Even an aristocrat could be nearly bankrupted by paying for the finery and jewels required to compete at court.

By creating an artificial demand for status that could only be met by staying at the costly “hotel” of Versailles, Louis ensured that the nobility became financially and socially dependent on him. This indebtedness placed them firmly within his influence.

The daily life of the nobles at Versailles was punctuated by elaborate ceremonies and frivolous rituals, from the king’s lever (waking) to his coucher (retiring to bed), reinforcing the hierarchy and reminding the nobility of their subservience. Each event was an opportunity for Louis to display his absolute power and for the nobles to compete for his attention in seemingly trivial yet politically significant ways—such as who might hand him his shirt or get the highly coveted chance to talk to him while he sat on the toilet.

Louis XIV’s motivations for establishing Versailles as the heart of French nobility were manifold and deeply rooted in his experiences during the Fronde — a series of civil wars where the nobility, along with external enemies like Spain, threatened the young king’s reign. These events profoundly shaped Louis’s approach to governance, driving him to dilute the power of the aristocracy by binding them to his court.

By transforming the palace into a luxurious trap, Versailles became a brilliant and bonkers exercise in absolute power— an absurd royal hotel where the guests stayed not merely at the king’s pleasure but for his pleasure and security. As the song goes, they could check out, but they could never leave.