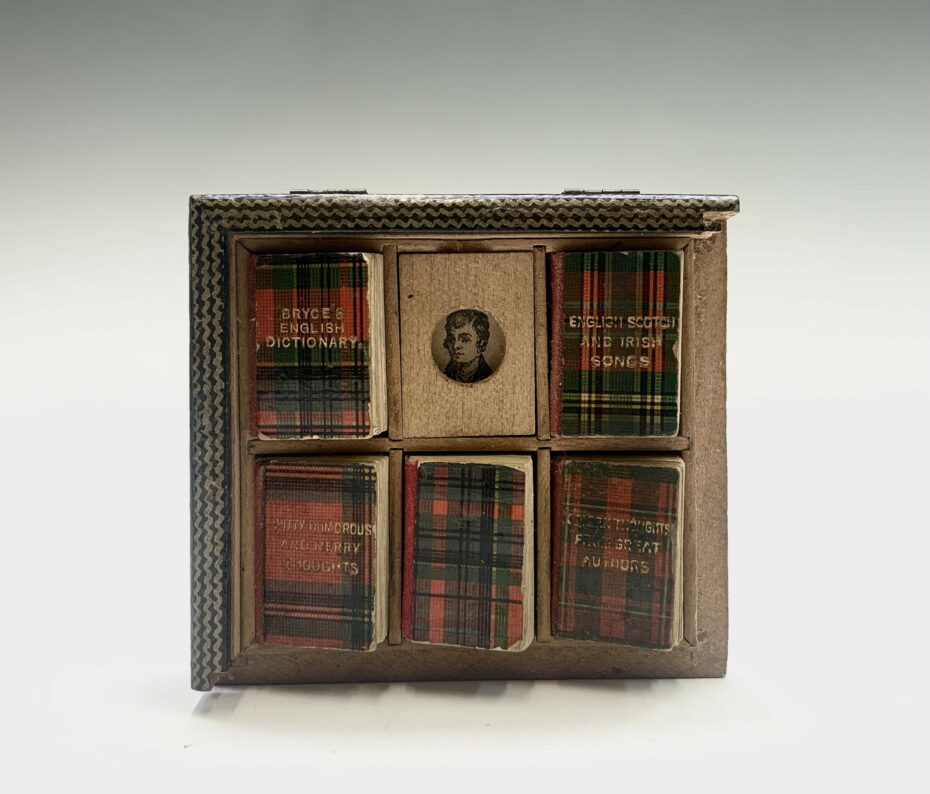

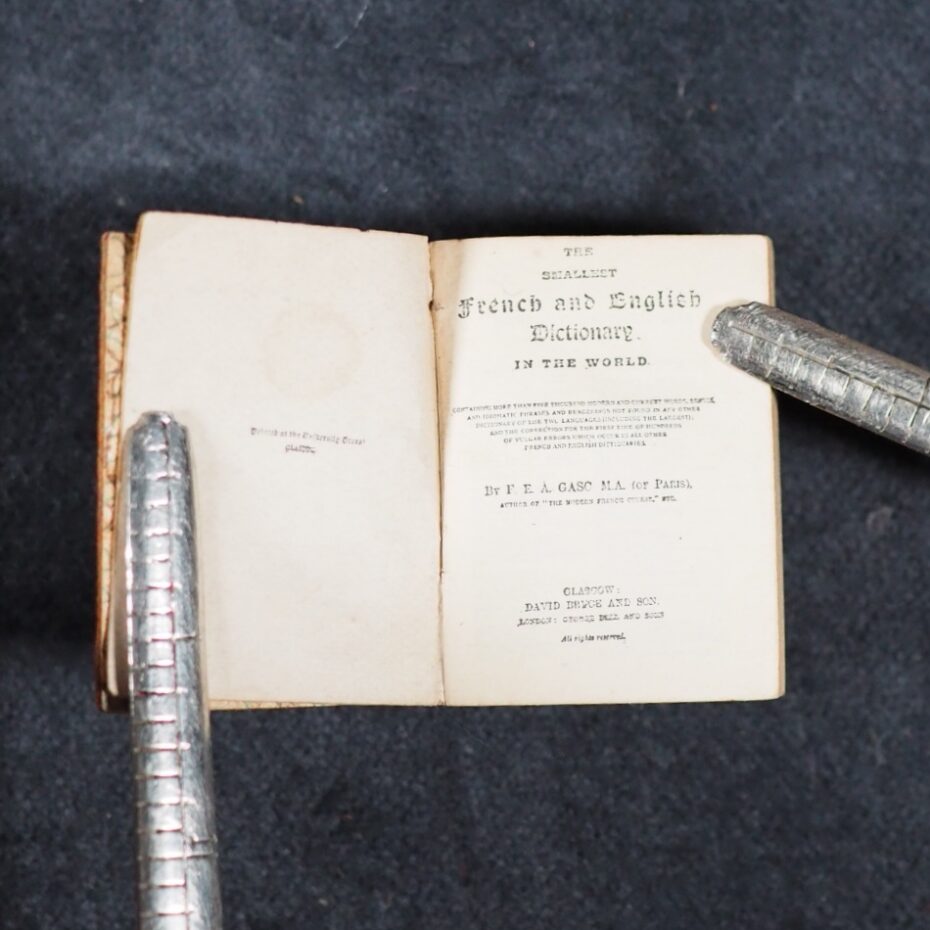

It all started when I was looking to source a miniature French to English dictionary (as you do) for Messy Nessy’s Cabinet in Paris (coming soon). It wasn’t long before I found myself obsessing over a 2 x 2.7 cm red leather dictionary from the 1890s contained within a metal case complete with a magnifying glass in the front. And you know by now I have this thing for teeny tiny stuff. Anyhoo. This exquisite little book just to happens to have been made by one of the most prolific miniature book publishers in the world, David Bryce, of Glasgow (1845-1923), who produced over 40 miniature titles at the turn of the century.

Allie Alvis, curator of Special Collections at the Winterthur Library gives us a little show & tell of her personal copy on her delightful Instagram account.

View this post on Instagram

Bryce utilized the latest advancements in photolithography — a technique involving photo reduction with electroplates — to shrink larger volumes to the smallest possible size. His collaboration with Oxford University Press was particularly advantageous because they possessed the method to create ultra-thin, opaque sheets known as ‘India paper,’ allowing for the production of exceptionally small textblocks. He also made use of the printing houses of Glasgow University, which currently holds a vast collection of his books.

But this got me thinking – how did miniature book publishing become a thing? And as it turns out, miniature book publishing has a history that spans centuries, driven by a variety of factors including practicality, artistic expression, and the desire for portability and novelty. The concept of miniature writing can be traced back to ancient civilizations. For example, cuneiform tablets from Mesopotamia were small and portable. During the medieval period, monks created illuminated manuscripts, some of which were small enough to be easily carried and used for personal devotion. When the printing press was invented by Johannes Gutenberg in the 15th century, it revolutionized book production and printers experimented with different sizes, including miniature formats. Aldus Manutius, a Venetian printer, is credited with producing some of the earliest portable, pocket-sized books in the late 15th and early 16th centuries which were popular among scholars and travellers. But the 19th century saw a surge in the popularity of miniature books as collectibles.

The Victorian fascination with small and intricate objects extended to books and advances in printing technology made it easier to produce high-quality miniature books. In the 20th century, miniature books became a niche market for collectors and bibliophiles as artists and bookbinders began to explore it as a form of artistic expression, creating unique and highly detailed works of art. And that pretty much brings us to the desirable collectible item they have become today. Antique miniature books, especially those from the 16th to 19th centuries, are highly prized and can fetch significant prices at auctions and from rare book dealers.

I guess I’m telling you all this because I either need help being talked off a ledge – or convincing that I absolutely do need the world’s smallest English to French dictionary for my miniatures museum at Messy Nessy’s Cabinet. Help.