Picture Paris at the turn of the 20th century: a city drenched in absinthe, artistic ambition, and outrageous fashion choices. Amid the bohemian splendor of the Belle Époque, a woman named Renée Vivien, a Brit in Paris, emerged as a poetic powerhouse and an icon of Sapphic love. Move over, Oscar Wilde, it’s time we met this literary diva.

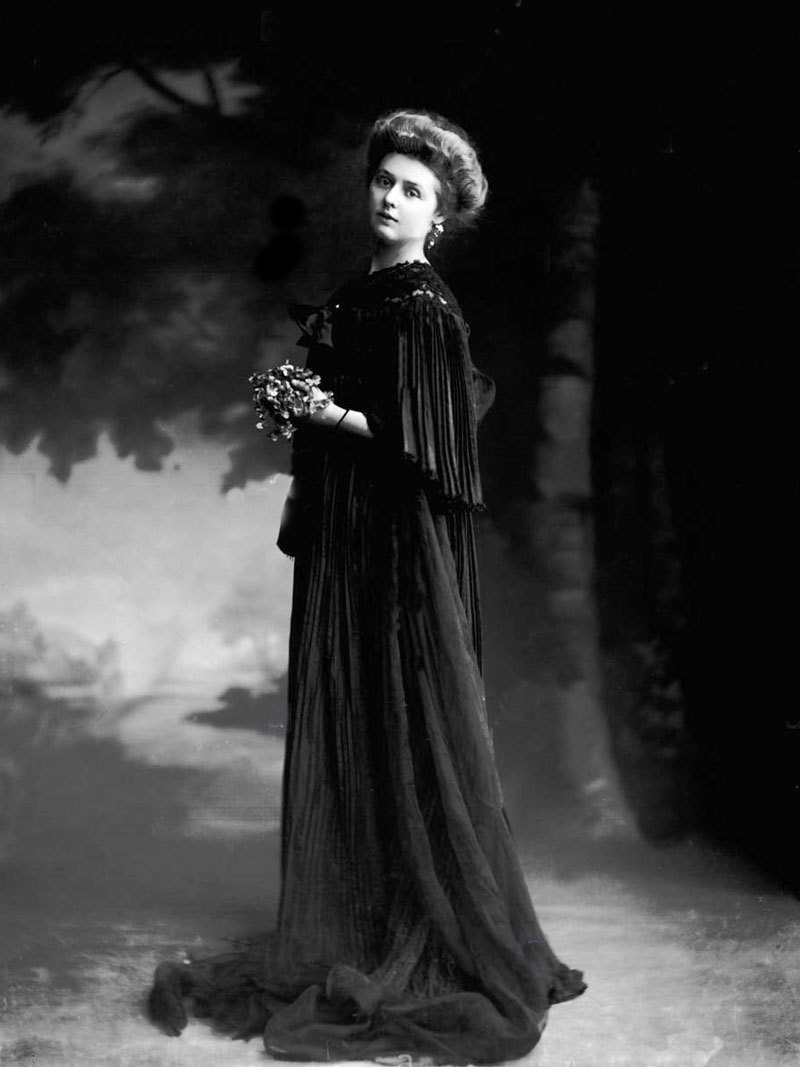

Renée Vivien, born Pauline Mary Tarn in 1877, was as enigmatic as she was extravagant. She swapped her mundane British upbringing for the artistic allure of Paris, and in doing so, transformed herself into a high-profile poetess and a beacon of lesbian chic. Vivien was known not just for her verses but for her lavish lifestyle, which included exotic pets, elaborate salons, and a wardrobe that would make anyone green with envy. At a time when women’s voices were often stifled, Renée Vivien’s verses, filled with longing and adoration for other women, were unapologetically bold.

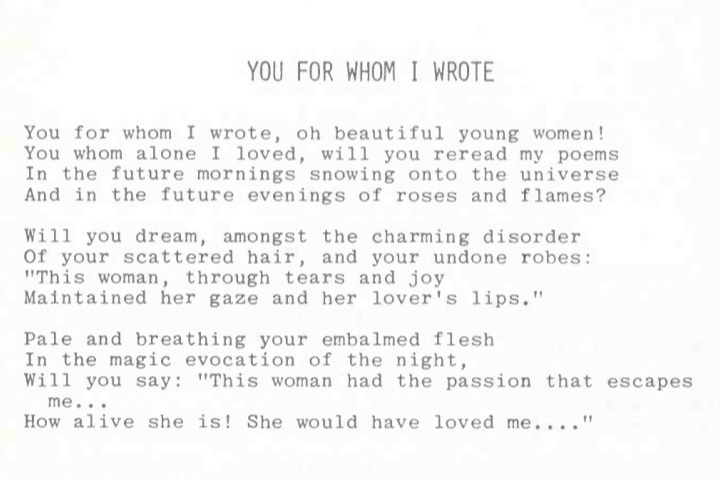

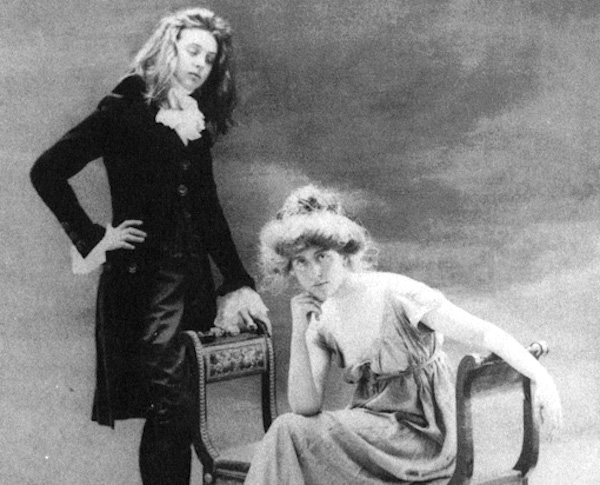

Renée often felt she had to hide her gender publishing her first two books under the genderless pseudonym “R. Vivien” and often signed her work destined for critics with the masculine form of her name, “Rene Vivien”. She once attended a lecture with her then-girlfriend Natalie Barney, but the pair began giggling so much that they had to leave. The male lecturer was talking about an anonymously published book of love poems as the pinnacle depiction of a young man’s desire’s towards women. In actual fact, it was Viven’s book which she had written about her girlfriend, Nathalie.

Vivien’s life was as poetic as her work. She moved in the dazzling circles of Belle Époque Paris, rubbing elbows with the likes of Colette and Natalie Barney, another literary goddess of the time, with whom she had a tumultuous relationship. She wintered in Egypt and travelled through China and the Middle East, but her romantic escapades, intensely captured in her poetry, is what we’ll remember her for. She had a secret relationship with one of the Parisian Rothschilds, Baroness Hélène van Zuylen, and although the affair could not be made public because of Hélène position in society, Vivien considered herself married to the Baroness, who would ultimately break her heart. Her poetry collections, such as “Cendres et Poussières” (Ashes and Dust) and “Études et Préludes” (Studies and Preludes), are now hailed as masterpieces of early 20th-century literature. Vivien’s verses often drew on classical mythology, transforming ancient tales into modern declarations of female desire. She didn’t just write poems; she crafted a new mythos where women could be both muse and lover, goddess and mortal.

But Renée Vivien wasn’t just a poet; she was a spectacle. She kept a menagerie of exotic animals, including a pet lioness named “Djuna,” because why settle for a cat when you can have a lioness? Her fashion choices were equally extravagant, favoring flowing gowns and opulent accessories that made her look like she’d stepped out of a Pre-Raphaelite painting.

Sadly, Renée Vivien’s life was as brief as it was brilliant. In 1907, when the Baroness left Vivien for another woman, Vivien turned to alcohol and drugs. While visiting London in 1908, Vivien tried to kill herself by drinking an excess of laudanum, she barely ate began wasting away before the eyes of her friends. Colette, who was Vivien’s neighbour at the time, immortalised these troubled years of her life in The Pure and the Impure, a series of conversations with “ghosts” about sex, gender and attraction. Colette considered it her best book and one of the longest conversations takes place in Vivien’s “dark and shadowy, with incense burning like a funeral parlor”.

“Voluptuaries, consumed by their senses, always begin by flinging themselves with a great display of frenzy into an abyss. But they survive, they come to the surface again. And they develop a routine of the abyss: “It’s four o’clock… At five I have my abyss…”

The Pure and the Impure, Colette

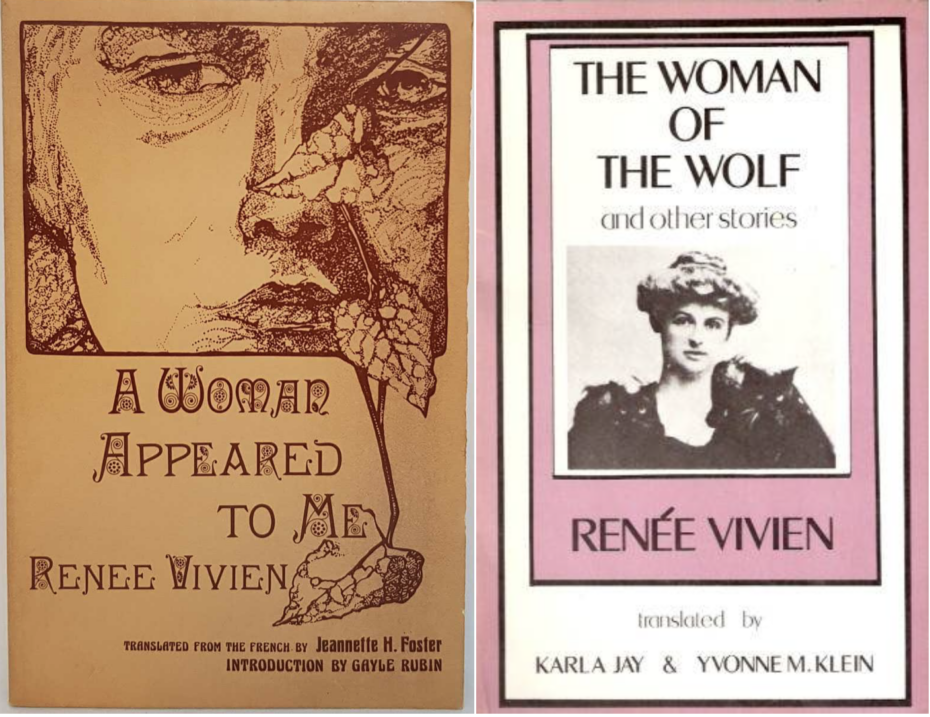

She passed away in 1909. The cause of death was reported at the time as “lung congestion”, but most likely it was a result of pneumonia complicated by alcoholism, drug abuse, and anorexia nervosa. At the age of 32, Vivien left behind a legacy that would take decades to fully appreciate. But in the spirit of the Belle Époque, where art and love were celebrated in all their forms, Vivien’s work has found its way back into the limelight, which is enjoying a well-deserved revival in the literary world.

Today, Renée Vivien is becoming celebrated as a trailblazer of lesbian literature, a poet whose work defied the conventions of her time and paved the way for future generations. Her verses resonate with the timeless themes of love, loss, and longing, capturing the hearts of readers all over again.

When in Paris, take a moment to visit the small public square is named in her honor in Paris: ‘place Renée-Vivien’, in the Marais. Raise a glass to the lioness of Belle Époque poetry, whose words continue to roar with passion and elegance. In a city that thrives on romance and revolution, she remains a beacon of both, reminding us that true artistry is never truly lost — it just waits to be rediscovered.