Julia Margaret Cameron revolutionized the world of photography. Known for her dreamy, soft-focus images and dramatic compositions, Cameron was the queen of Victorian portraiture. She was ahead of her time, doing everything differently before it was cool.

Cameron was a late bloomer artistically, she didn’t pick up a camera until she was 48. Her daughter Julia and son-in-law Charles Norman gifted her a camera, probably hoping she’d find a hobby. Little did they know they were unleashing a creative storm. Cameron dove into photography with the enthusiasm of a teenager with a new smartphone, quickly developing a style that was completely unique.

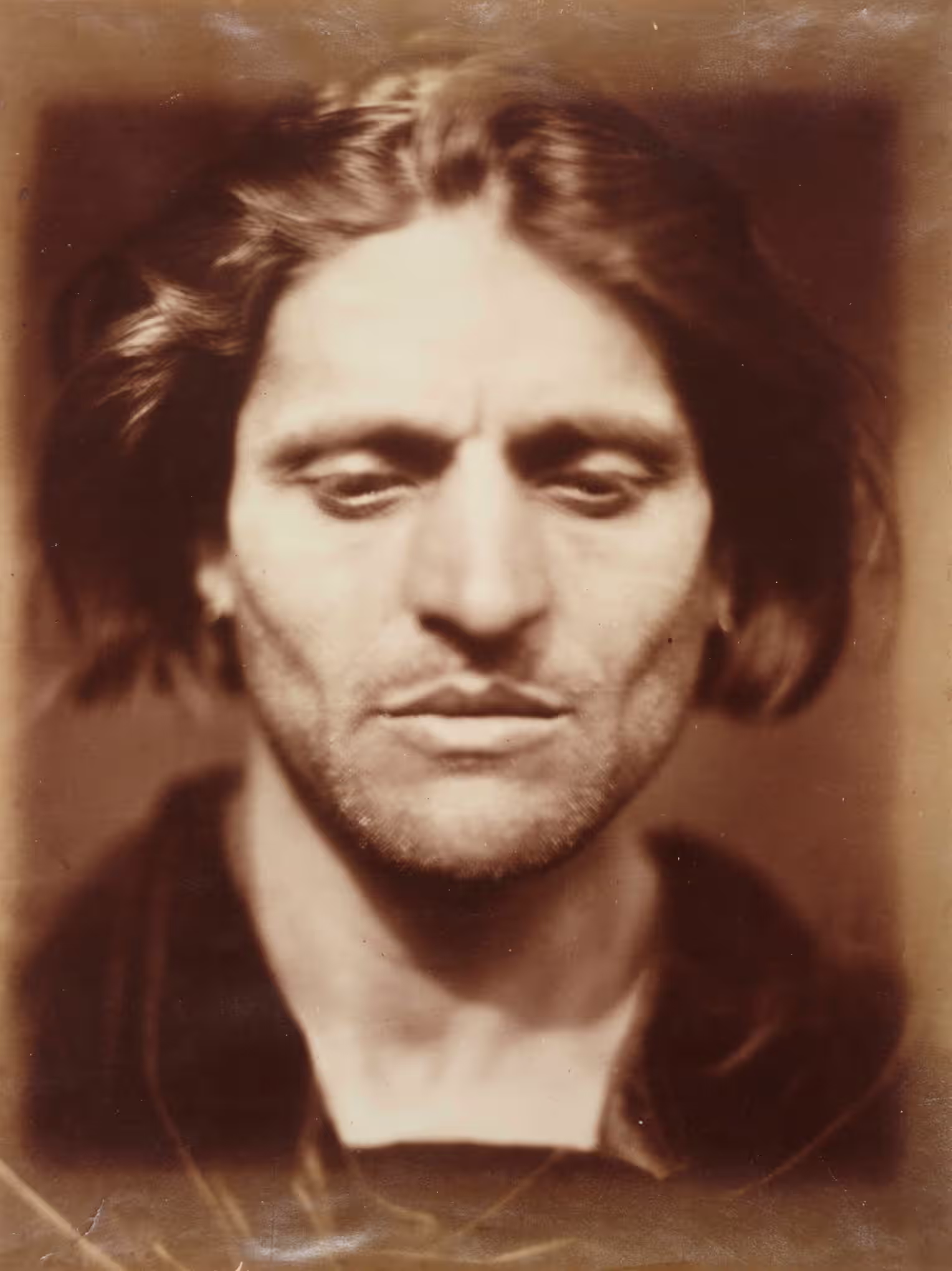

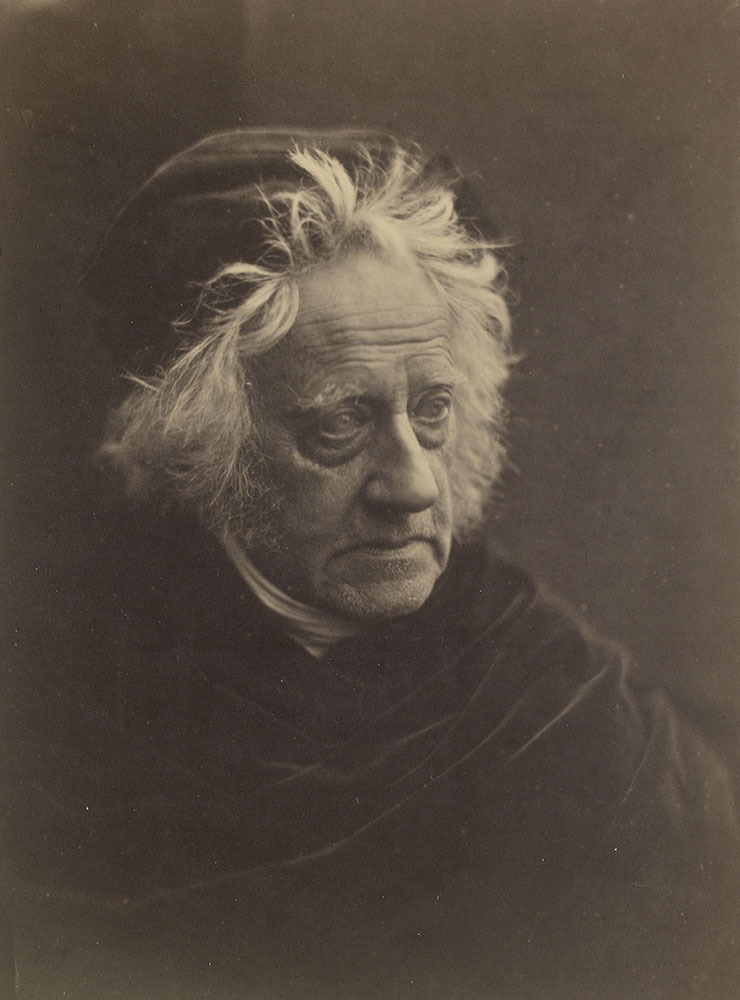

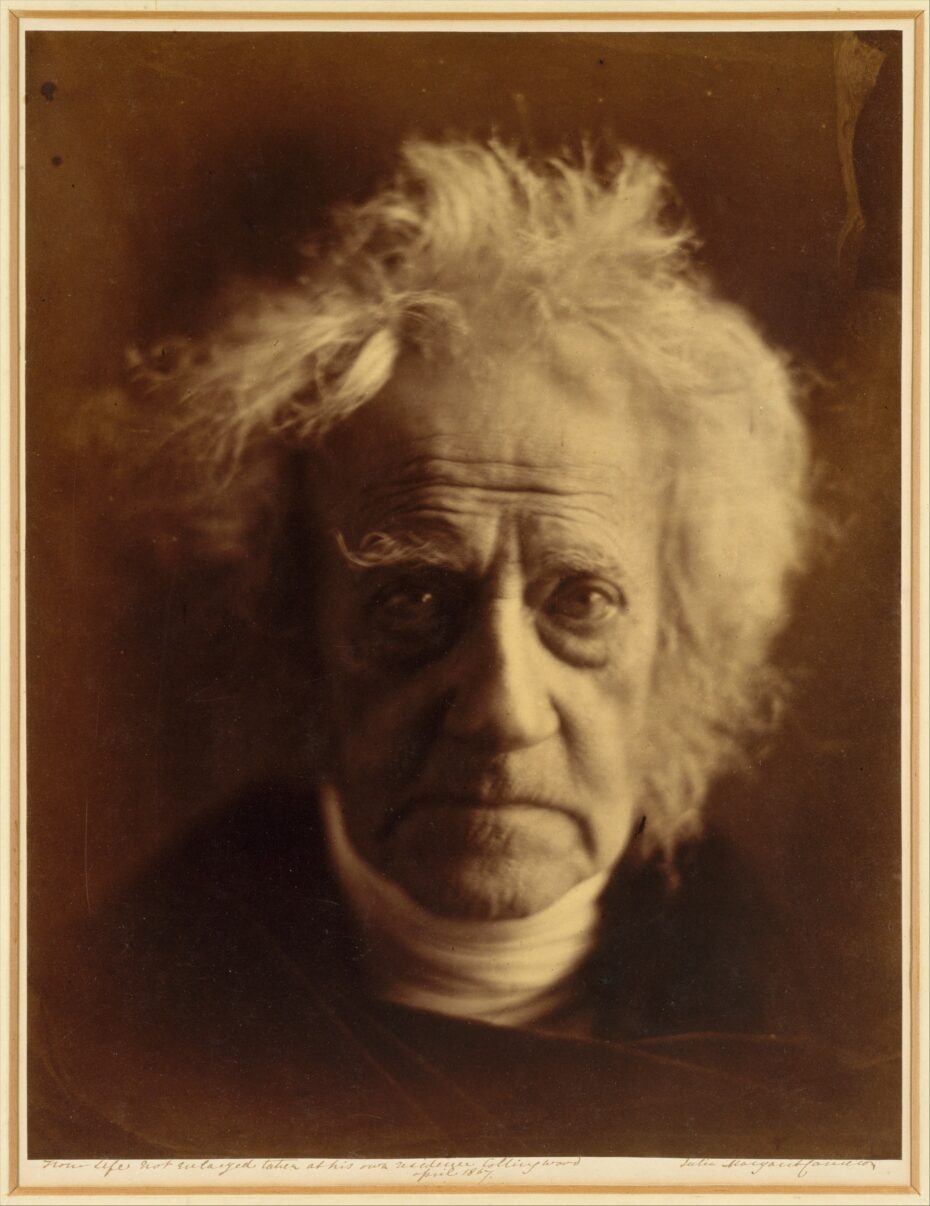

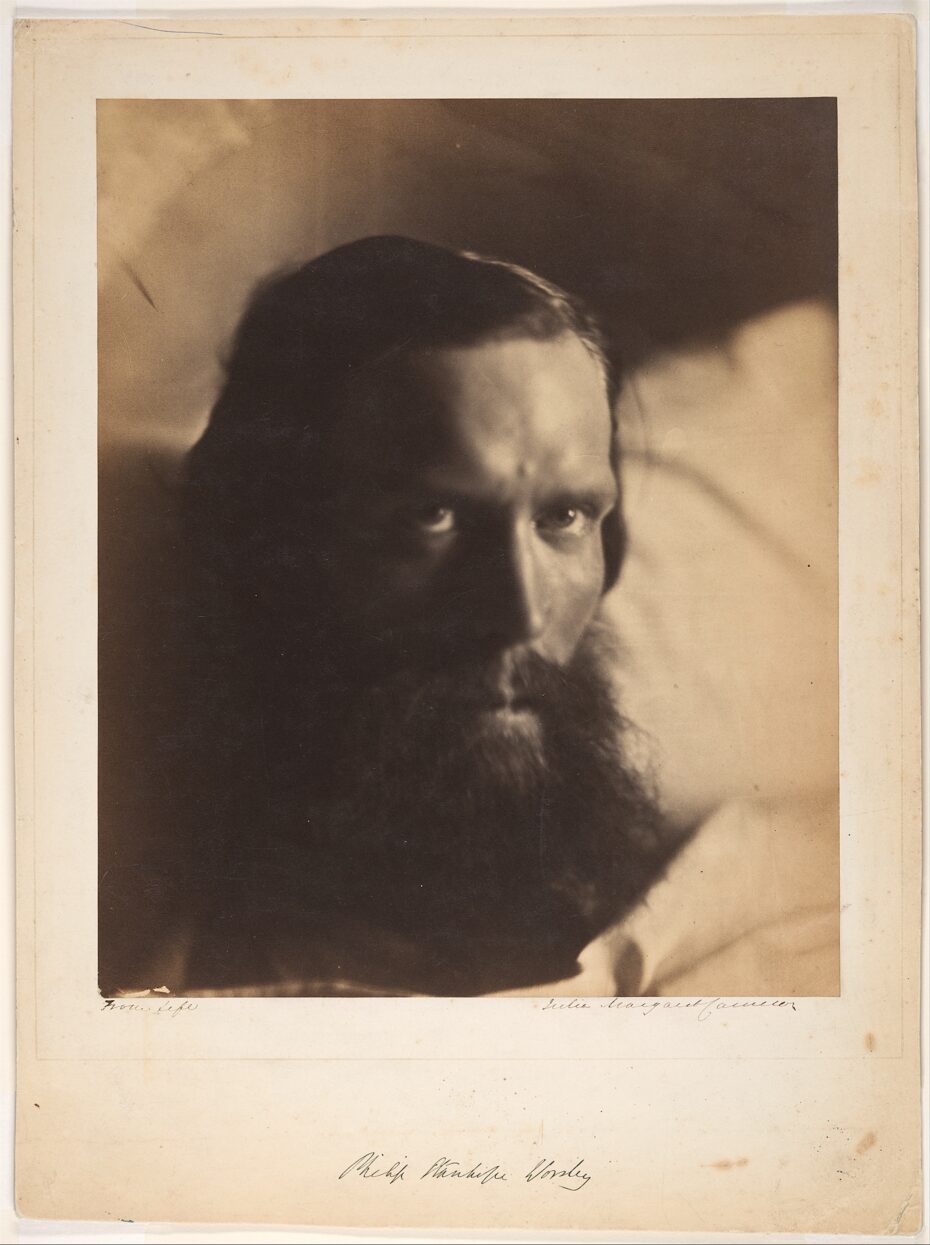

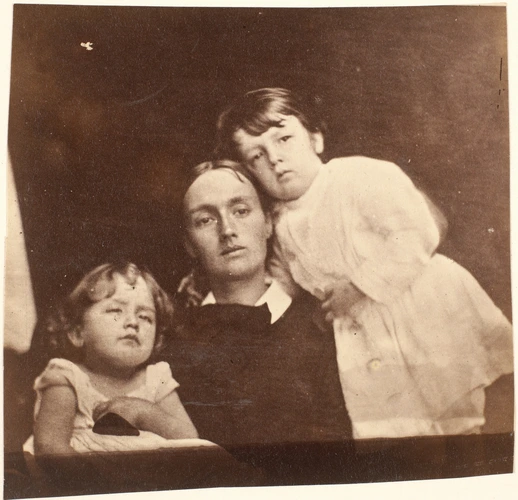

Cameron embraced soft focus and long exposure times, turning her subjects into ethereal beings straight out of a dream — or a slightly foggy morning. While her contemporaries were busy making sure every detail was pin-sharp, Cameron was all about that artistic blur, capturing the “soul” of her subjects.

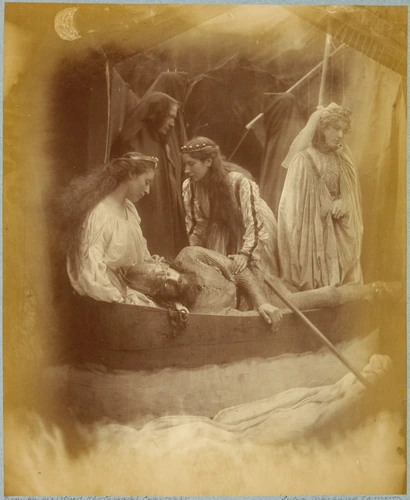

Cameron didn’t just take portraits; she staged epic scenes worthy of a grand-scale oil painting. Her inspirations came from literature, mythology, and religion. Women and children were her favorite subjects, often dressed up and posed like they were in a play. She elevated the simplest subjects to the status of “high art”, even when it was just her niece in a bedsheet posing as a Grecian muse.

Julia Margaret was born in 1815 in Calcutta, to a family that was a blend of British stiff upper lip and French flair. Her father, James Pattle, was a bigwig in the East India Company, and her mother, Adeline de l’Etang, had roots in French nobility. Julia was shipped off to Europe for her education, where she picked up a taste for art and literature. In 1838, she married Charles Hay Cameron, a jurist. They moved to England in 1848, and frequented the intellectual circles of Victorian society.

Hanging out with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Cameron soaked up their love for naturalism and drama. These guys were “it” for the Victorian art scene, and their influence on Cameron was undeniable. She translated their vibrant colors and detailed brushwork into her black-and-white photographs, creating characters that felt like they might just jump out of the frame and recite a sonnet.

But at the time, many dismissed Cameron’s photos as nothing but blurry mistakes. While some of the artistic community understood her work, critics called it “technically flawed,” a claim laced with sexism. Over time however, people started to see her as the genius she was. Though she was somewhat well-known during her life, she reached a new status of fame nearly 50 years after her death in 1879, due to her goddaughter, who happened to be Virginia Woolf. The British author was Cameron’s niece, and a champion of her work. In 1926, she published the first major collection of Cameron’s work, Victorian Photographs of Famous Men and Fair Women with Roger Fry. The book led to a rediscovery of Cameron in the mid-twentieth century by historians, photographers, and the general public.

Today, Cameron’s work is highly respected, with her portraits hanging in museums around the globe. She paved the way for every photographer who’s ever dared to break the rules and follow their vision, no matter how many critics rolled their eyes.

Julia Margaret Cameron wasn’t just a photographer; she was a rule-breaker, and an artist who saw the potential for photography to be more than just a way to document reality. Through her lens, she captured not just faces but the essence of an era. Her legacy continues to inspire anyone who’s ever picked up a camera and thought, “What if I tried something different?” So, here’s to Cameron, the grandmother of glamour shots, the original queen of soft focus, and the woman who showed us that sometimes, it’s good to see the world a little bit out of focus.

If you’re ever on the Isle of Wight, don’t miss a chance to visit Dimbola, the former home of the Victorian photographer which has now been turned into a museum.