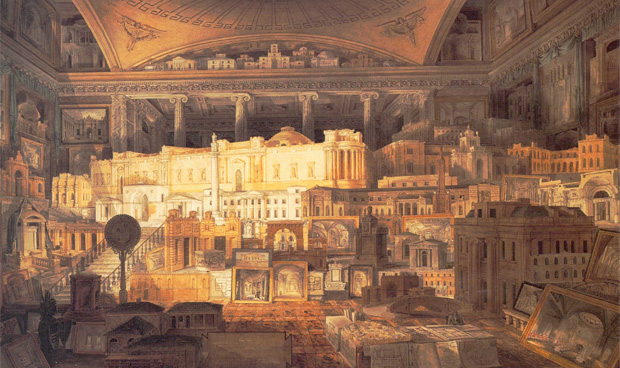

If it took you this long to identify one of the most epic genres of art history, welcome to the club. We must have skipped class that day. The aesthetic: a lost civilization – its crumbling and vaguely familiar architectural forms dramatically lit by a sunset backdrop, and in the foreground, a congregation of folks are musing amidst the ruins. That’s called ‘Capriccio‘; a genre introduced in the Renaissance combining the real and the fanciful, juxtaposing familiar elements of classical architecture with fantastical ones; an artist’s vision of a landscape unhindered by historical accuracy or geographical and physical limitations. The artist gets to move temples and pillars, play with perspectives, conjure whimsical skylines and build views that only exist in their imagination. Before AI-generated images were flooding our instagram feeds, prompting us to wonder if such places exists, there was the art of capriccio…

Capriccio would gestate in Italy in the 16th century from the illusionistic ceiling paintings of the Renaissance and the frescos that were popular during this period. It was during the 18th century that the movement developed and became popular through artists such as Alessandro Salucci and Viviano Codazzi. Their decorative architectural paintings would begin to include a rearrangement of monuments and ancient ruins, a fantastical if not slightly melancholic view of past and present, colliding together on a canvas. A view of what could have been but never was, intermingles with proposed greatness that has been lost over the centuries. An empire fallen and gone to ruin but still echoes through the ages depicted in a landscape of imagination and recognition.

Giovanni Battista Piranesi, or Piranesi, as he was known, was an Italian artist whose engravings took Capriccio a step further. In the 1740s, Piranesi created a series of works entitled ‘Prisons (Carceri). These were a darker claustrophobic look at the inner workings of an imagined situation. Gone were the open grand views of looming stone structures; what we see are engravings of mechanical precision. A labyrinthine geometric vault-like enclosure that would resemble something from the Industrial Revolution; more than the ‘Age of Enlightenment’.

In England, the artist Joseph Michael Gandy would reimagine the work of the great architect Sir John Soane. Gandy had spent some years in Italy and would be inspired by the works of Piranesi. His work would be used to promote the designs of Soane as an imagined early form of ‘Psychogeography’. Gandy would place the very real architecture of Soane in a fantasy setting of his making; ancient scenes, a dramatic casting, grand views of lush landscapes and monumental views, to help sell the very real work of his partner.

The artists of Capriccio would find popularity and appeal with a cultural renaissance. A past and present juxtaposed into each other’s chronology, the world was changing but there was still a prominent presence of what had come before, scattered throughout Europe and the Middle East. People were looking to the future but still somewhat stuck in the past. In a society that was still highly religious, biblical art was still extremely popular. The Baroque influence of the power and grandiose of the Catholic church can be seen throughout many works; the ever-looming presence of majesty or higher power that builds and takes away.

A human element can appear in many of the paintings of Capriccio, firstly for the use of scale but more significantly to show the journey of time. Piranesi depicts a drunken and restless congregation of people morbidly lamenting the fall of something once great as they mingle with the ruins of Rome and his imaginary structures intertwined with the past.

What does Capriccio strive to convey then exactly? A romantic hope? The Industrial Revolution was just around the corner, a time when magic and religion would soon be on the decline. Archaeology was still largely in its infancy, creating a nostalgic reverie of a past relatively still undiscovered, as well as a heightened sense of extravagance, a look to the future and a fear of forgetting. To lose our memories means we are nothing at all.

The allure of Capriccio lies in the unpredictability of an art form that lets an artist imagine the unbuildable and the unfathomable before the end of the past. Capriccio paintings taps into a deep, almost primal part of our consciousness that yearns for exploration, discovery, and the thrill of the unknown. Ultimately, the enduring appeal of capriccio art lies in its ability to inspire. It reminds us that the world is not always as it seems, and that through imagination, we can reshape our reality into something more beautiful, more mysterious, and infinitely more intriguing.