It appears we’ve come full circle. Picture a time before smartphones, Youtube, Tik Tok, streaming services, or even the modern movie theater as we know it — a time when a few moments of visual entertainment involved peeking into a mysterious, boxy machine and cranking a handle. Back in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, if you wanted to watch something “on demand,” your best bet was to drop a coin into one of two contraptions: the Mutoscope or the Kinetoscope. Both devices were early precursors to cinema, captivating audiences with flickering images and bringing the first taste of moving pictures to the masses. Take a peep into the dawn of the moving image…

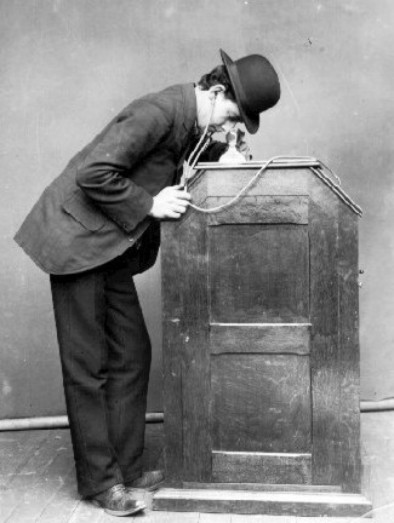

The story of these lost technologies begins with the Kinetoscope, a creation by Thomas Edison and his assistant, William Kennedy Laurie Dickson, in 1891. The Kinetoscope was the first successful device to show moving pictures. It worked by running a strip of celluloid film, perforated on both sides, past a light bulb and a rapidly moving shutter. As you peered through a peephole at the top, the mechanism flickered the frames in quick succession, creating the illusion of motion. The Kinetoscope became a sensation when it premiered in parlors and penny arcades, allowing people to watch short films for the price of a coin. The earliest films showed vaudeville acts, boxers sparring, jugglers, and brief scenes of everyday life.

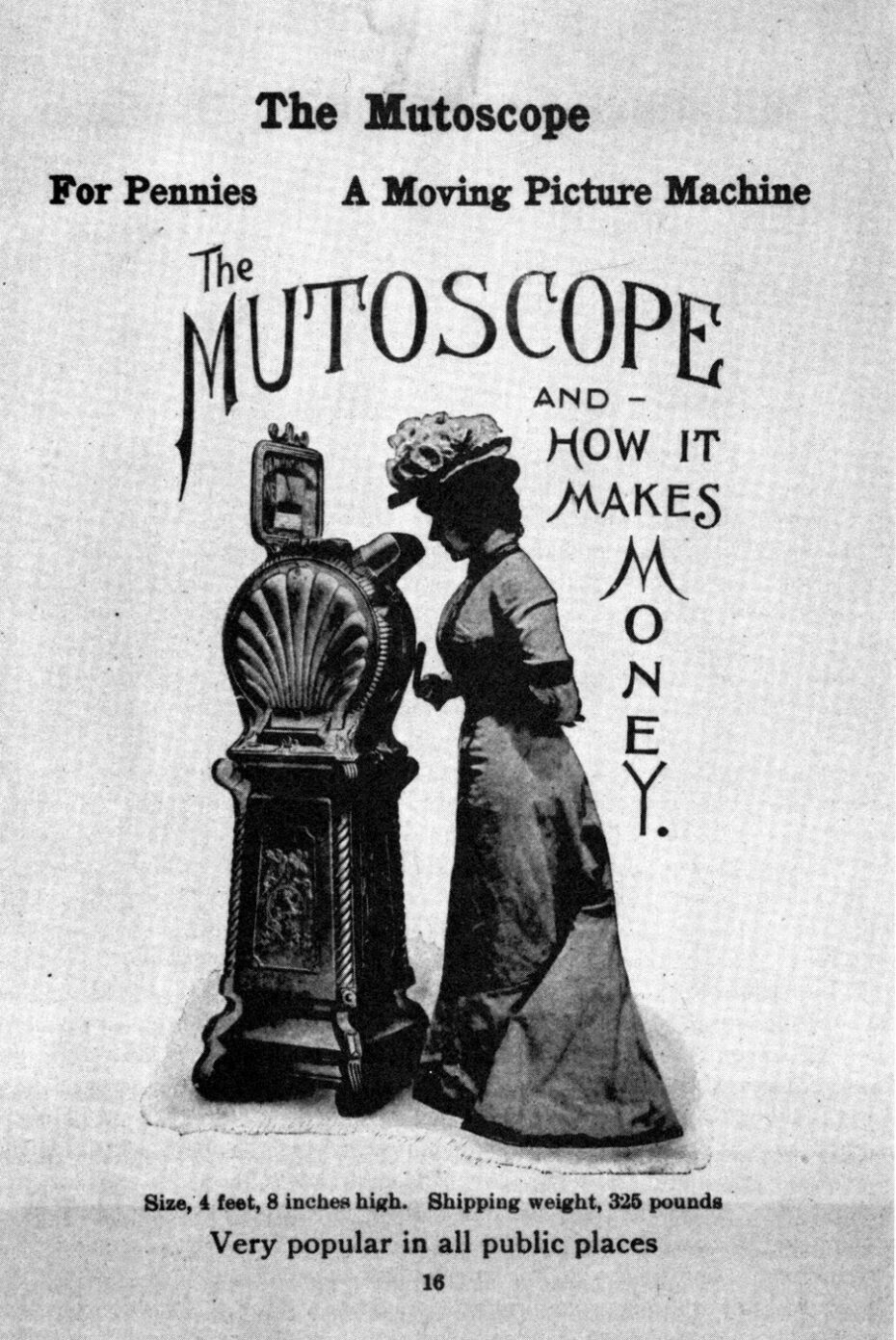

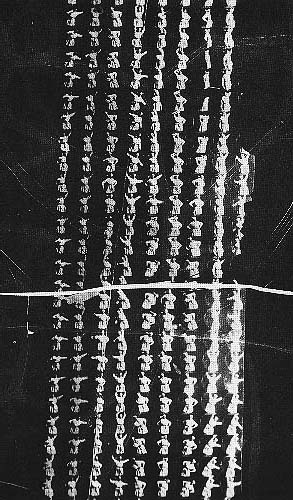

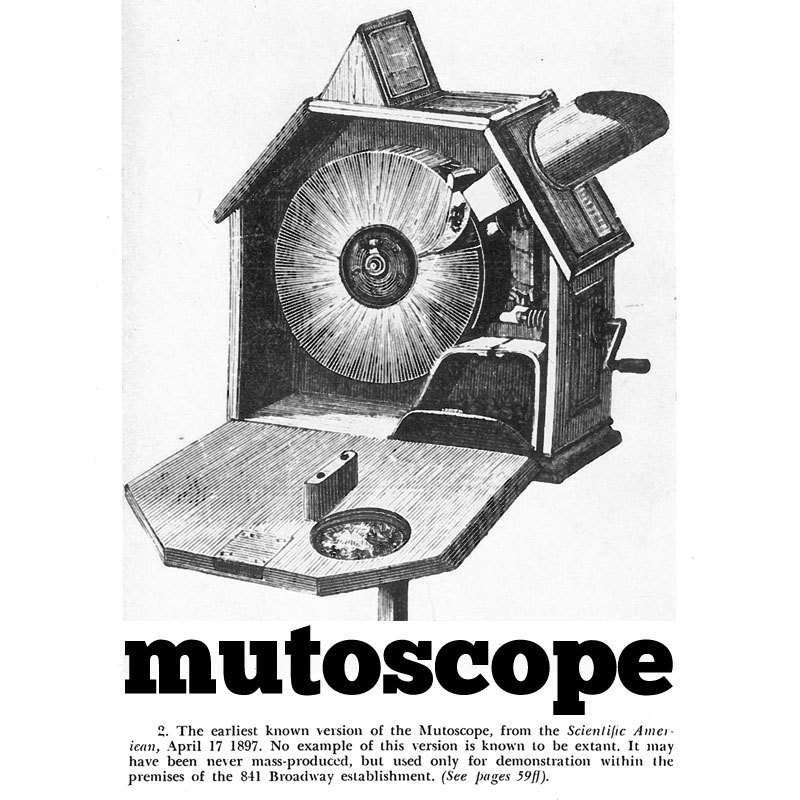

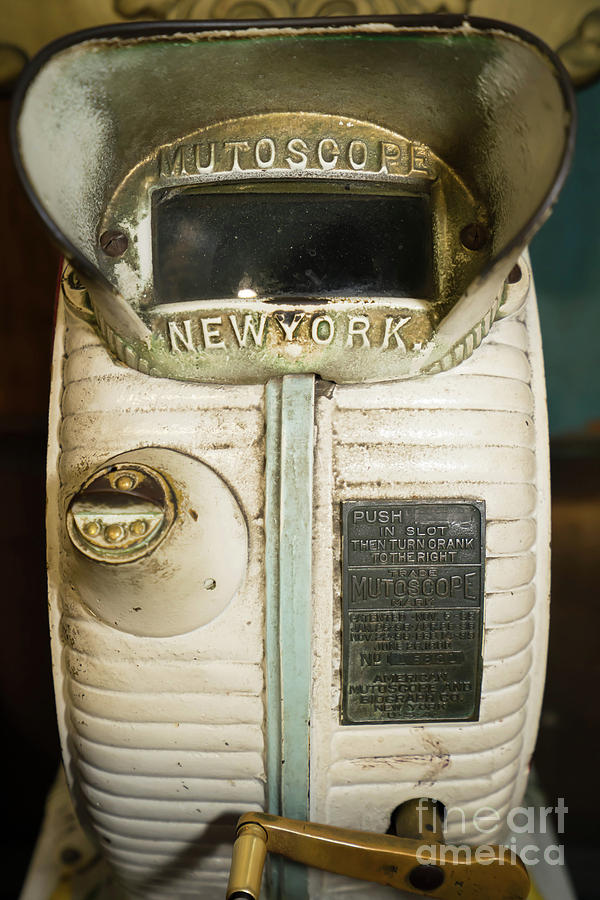

While the Kinetoscope dazzled with its use of newfangled film technology, it had a competitor that was even simpler and more user-friendly: the Mutoscope, invented by Herman Casler in 1894. The Mutoscope took a different approach to creating moving images. Instead of using a continuous strip of film, it relied on a drum filled with hundreds of stiff cards, each one holding a single photograph. When you turned the crank on the side of the machine, these cards flipped rapidly past a viewing lens, creating a jerky but charming moving picture — much like a mechanical flipbook.

Unlike the Kinetoscope, which was electrically powered, the Mutoscope was entirely manual. The viewer had to turn the crank to see the images flip by, which added a tactile, interactive element to the experience. The speed of the crank controlled the speed of the images, so viewers could watch at their own pace, stopping or rewinding to catch a missed detail or speeding up for comedic effect. It was an analog delight that gave users a sense of control over their mini-movie.

Both the Kinetoscope and the Mutoscope offered a smorgasbord of early visual entertainment. Edison’s Kinetoscope reels often featured short scenes of daily life, snippets of vaudeville performances, strongmen lifting weights, dancers, and comic sketches. Some of the earliest famous films included “The Kiss,” which caused quite a stir with its brief depiction of a couple kissing, and was one of the first films ever shown commercially to the public. Around 18 seconds long, it depicts a re-enactment of the kiss between May Irwin and John Rice from the final scene of the stage musical “The Widow Jones”. The film was directed by William Heise for Thomas Edison.

The Mutoscope, on the other hand, embraced a slightly more playful and cheeky repertoire. You could find reels of slapstick comedy, scenes of famous actors performing, and travelogues showcasing exotic places. But its real claim to fame came from its more risqué content. Nicknamed “What the Butler Saw” machines, Mutoscopes often featured images of bathing beauties, burlesque dancers, or daring scenes that skirted the boundaries of Victorian propriety. The Mutoscope’s appeal was partly due to this promise of a slightly naughty peek into a forbidden world.

While the Kinetoscope was groundbreaking in its use of film and the electric motor, it was also more complex and expensive to manufacture and maintain. The Mutoscope, being a simpler mechanical device with no need for electricity, was cheaper, more durable, and easier to set up in public places like arcades, train stations, and amusement parks. Additionally, the Mutoscope’s hand-cranked mechanism allowed users to control the viewing experience, adding an element of personal engagement that the Kinetoscope lacked.

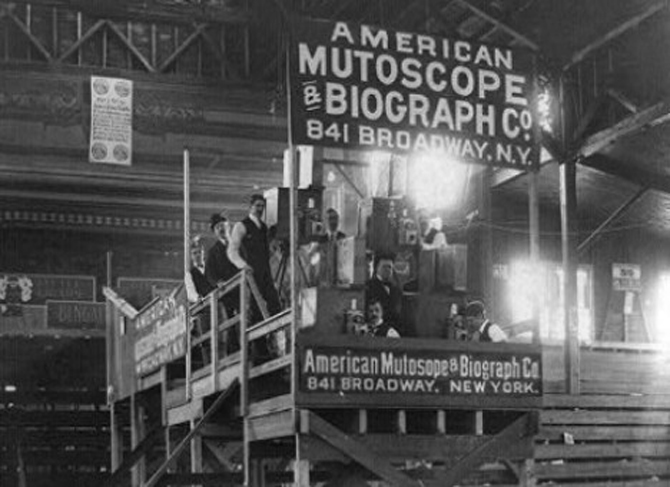

The Mutoscope quickly became a fixture in public venues. They were robust and rugged, built to withstand countless eager viewers turning the crank to see the flickering images come to life. Moreover, they required no specialized knowledge or equipment to operate, making them accessible to a broad audience. The Mutoscope’s interactive, hands-on appeal and slightly risqué content made it a favorite for many. In 1898, Edison sued the American Mutoscope Company for copyright infringement.

By the early 1900s, both the Kinetoscope and the Mutoscope were beginning to face competition from newer technologies. As movie theaters with projectors and longer films became more common, the appeal of these early machines started to wane. The Kinetoscope was quickly overshadowed by the advent of projected cinema, while the Mutoscope continued to thrive in arcades and amusement parks into the 1920s and 1930s.

Eventually, as sound films (“talkies”) emerged and cinema technology evolved, both the Kinetoscope and the Mutoscope were gradually retired. The Kinetoscope, with its reliance on film and electricity, faded into obscurity, while many Mutoscopes remained as nostalgic novelties in carnivals and penny arcades up until the mid-20th century, most user unaware that these quirky devices were the original “movie machines.” which had captured the imaginations of millions, one frame at a time.

Today, the Kinetoscope and Mutoscope are celebrated as charming relics of a bygone era, preserved by collectors, museums, and vintage enthusiasts. They represent the pioneering spirit of early cinema, when inventors were exploring new ways to bring the magic of motion to life. Their flickering images, grainy and jerky by today’s standards, hold a special place in the history of entertainment.

In a world dominated by digital screens, these mechanical marvels remind us of a time when moving pictures were a new and wondrous novelty. The Kinetoscope dazzled with its innovative use of film, while the Mutoscope charmed with its simplicity and hands-on fun. Together, they tell the story of how our love for moving images began — a flicker, a crank, and a coin at a time.