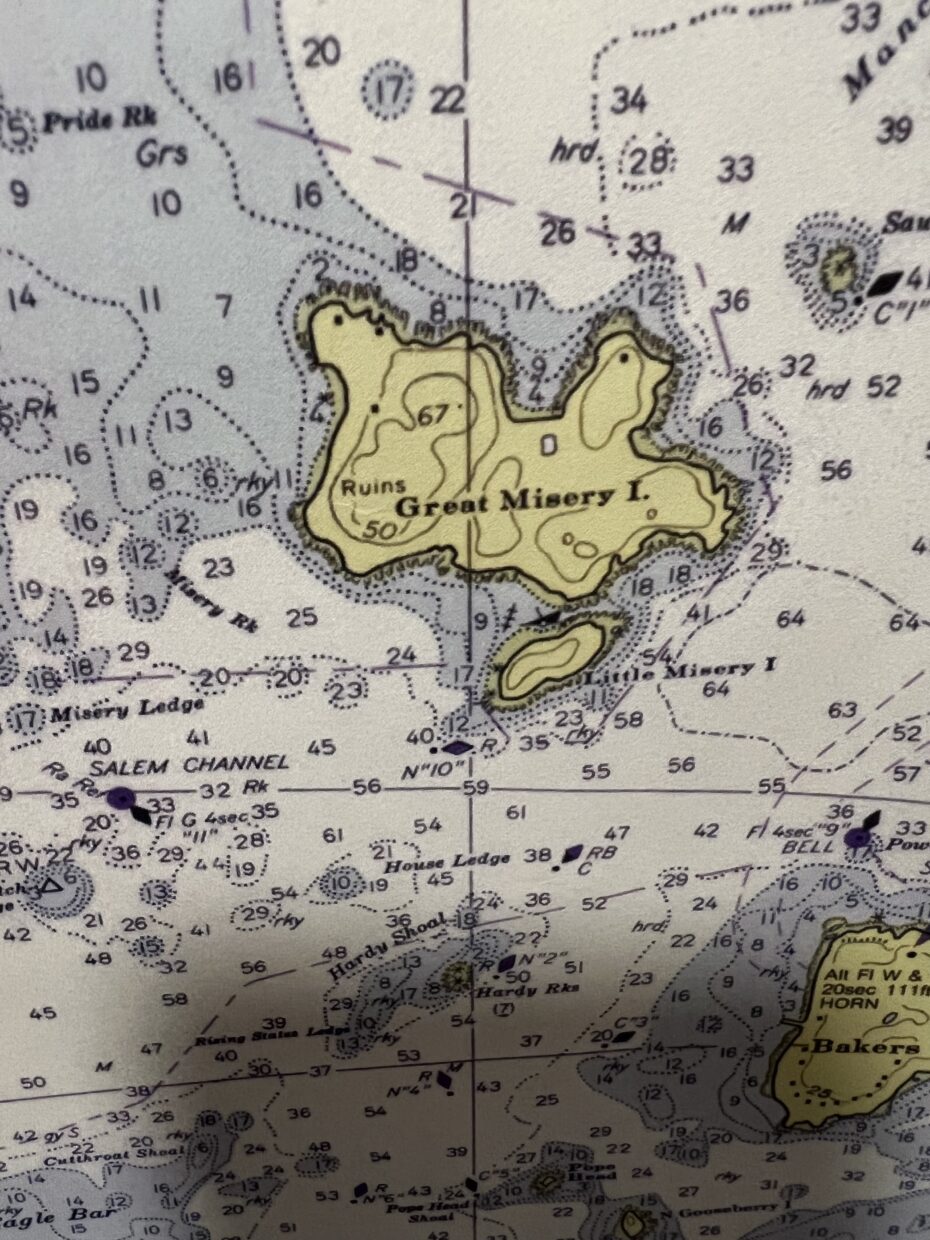

Whilst looking recently at an old nautical map of the North Shore coastline of Massachusetts, one tiny island caught our eye because of its mysterious sounding name: Great Misery Island! Further inspection of the map showed that the island had no towns, roads or any other topographical features apart from in the south west corner, a small mark saying ‘RUINS’.

What tragedy had befallen this forgotten island lying in Salem Sound to give it such an enchanting name? After finding someone to sail us out there, we set off to explore an island that has been abandoned for nearly a hundred years, but had one time been a swinging hot spot of the Jazz Age, complete with the ruins of a casino, luxury summer houses, overgrown golf courses and cursed shipwrecks…

Today Salem is world famous for the witch trails of 1692 which has given rise to a juggernaut tourist trade each October that sees hundreds of thousands of visitors in witch hats descend on this small, charming city by the ocean. But two hundred years ago, Salem was more known as a bustling, seafaring city, the United States’ most busiest port that dwarfed Boston, Philadelphia and even New York. Once Salem’s wharfs were crowded with frigates, barks, brigs and schooners, a forest of tall ships and masts that rose against the salty sky.

This was the city that first brought back spices, silks, coffee and china from far flung Zanzibar, Ceylon and Madagascar, where a young Nathanial Hawthorne worked in a waterfront custom house that in 1850 was bringing in a yearly import of over seven million dollars in duties alone. This was a ramshackle city where an enterprising Salem lad could be a cabin boy at fourteen, a captain at twenty and if lucky by forty, had amassed a fortune and retired to live in some of the grandest Colonial mansions to be found in North America.

The illustrious days of far flung travel, trade and adventure may be long gone, but Salem’s harbour still bustles with ships, pleasure boats, lobstermen, luxury yachts and ferries to Boston. We’re sailing to Great Misery Island however, on a vessel far more rudimentary; a small flat bottomed steel craft, retired from the Coast Guard that resembles a miniature version of the landing craft used by Marines in World War II. Named “Naumkeag“, for the Native American tribe that once lived on the North Shore, the ship’s flat front and lower-able ramp is perfect for our purpose, as Great Misery Island has no port or docks, just a rocky beachhead on which to land. “It’s like D-Day, only no-one’s shooting at you,” says Captain Mike, grizzled and cheerful as the small landing craft slams into the grey waters of the Atlantic, past small rocky outcrops named Bowditch Ledge, Whaleback and Satan’s Rock, until we catch our first sight of Great Misery Island, lying hull up on the horizon. Running up the pebbled beach, the landing craft’s ramp lowers and we disembark. “See you in four hours” says Captain Mike, reversing the old Coast Guard vessel and leaving us alone on this rocky, remote outpost in the Atlantic Ocean.

Despite its name, the first impressions of Great Misery Island are that it is actually quite peaceful and pretty. Covering just over eighty acres of upland forest, pleasant meadows and rocky shorelines, the last people lived here over a century ago before a wicked fire ravaged the holiday homes and entertainments, leaving only ruins. Today, left in the company of only wild deer and shorebirds, you wonder just how the island got its cursed sounding name.

According to Salem legend, way back in the 1620s, shipbuilder Captain Robert Moulton was marooned on the island during a winter storm, whilst harvesting lumber there. At first the island was known locally as ‘Moulton’s Misery’ before the more sinister sounding name stuck.

Leaving the beachhead and heading inland across a meadow of heather and wind flattened tall grass you catch the first glimpse of a human touch; a dozen stone pillars, about ten feet high and arranged in a curious pattern resembling an ancient stone henge. Their existence is far more pragmatic: they once supported a giant water tower, providing the holiday makers with fresh rain water. Its hard to imagine now in these remote surroundings, but Great Misery Island was once a swinging hotspot of the first decades of the 20th century.

The Misery Island Club was formed in 1901 as an offshore haven for the wealthy socialites of Boston and the North Shore. President Charles Hanks remarked, “Here one finds liberty and privacy, things most desired in modern civilization.” To liberty and privacy, the club began to add pleasure, installing a sumptuous club house, a nine hole golf course, tennis courts and a casino. There was even a neatly engineered saltwater swimming pool, carved out of the ocean at a place called Cocktail Cove, and twenty six summer cottages soon followed.

Heading towards the southwestern corner of the island you come across the remnants of one of these cottages, the one that had caught our eye on the nautical map marked ‘ruins.’ Once owned by three brothers, this summer house had one of the great forbidding addresses : Bleak House c/o Great Misery Island. Although the roof has long gone, you can see the remains of a tiled kitchen, the outline of rooms and lovely arched windows that gave views of the Atlantic. The stone walls are covered in orange lichen, the brine drenched ruins of a house perched atop the rocky coastline that the rains have beaten on for a hundred years.

Such was Great Misery Island’s glamour in its heyday that swanky periodicals such as House & Garden, and The House Beautiful came to visit; “Just off the shore […] are the eighty-six acres which make up picturesque Misery Island, flecked with charming summer cottages and bungalows. It was purchased for the use of the Misery Island Club, which began at once to improve the spot with such energy that in less than fifteen years a clubhouse, an ice-house, a caddy-house, and fine golf links have sprung up on the island. A prominent feature of the clubhouse is a large new dining-hall, as well as a cafe; there is also a smaller room used for private parties, and on the second floor are a dozen chambers and baths; in the spacious living-room are several pool tables.”

The largest collection of ruins can be found on the north shore, where there was once a casino overlooking the waterfront. Tumbled down walls, crumbling staircases and walled off rooms are all that remain today of swanky rooms that were once filled with the clinking of cocktail glasses, gramophone records and the sparkling chatter of the well heeled pleasure seekers escaping Boston for a long weekend.

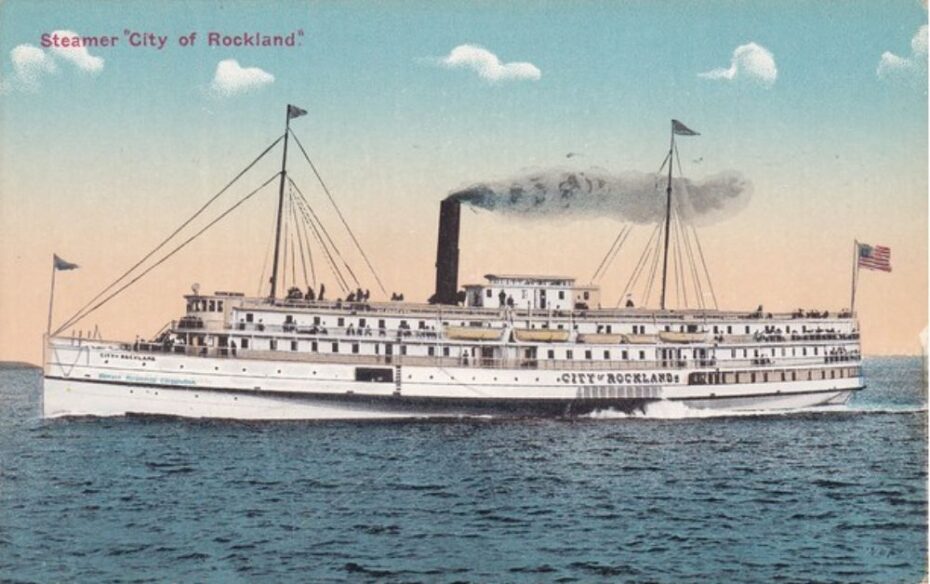

A mysterious sounding abandoned island wouldn’t be complete without a shipwreck or two: venture to the southernmost tip of the island and a short distance across the water you’ll see the forest outcrop of the four acres of neighboring Little Misery Island. Explore at low tide and a seaweed laden row of wooded posts emerge from the surf: this barnacle encrusted spectacle are the ribs of an old steamship, the SS City of Rockland.

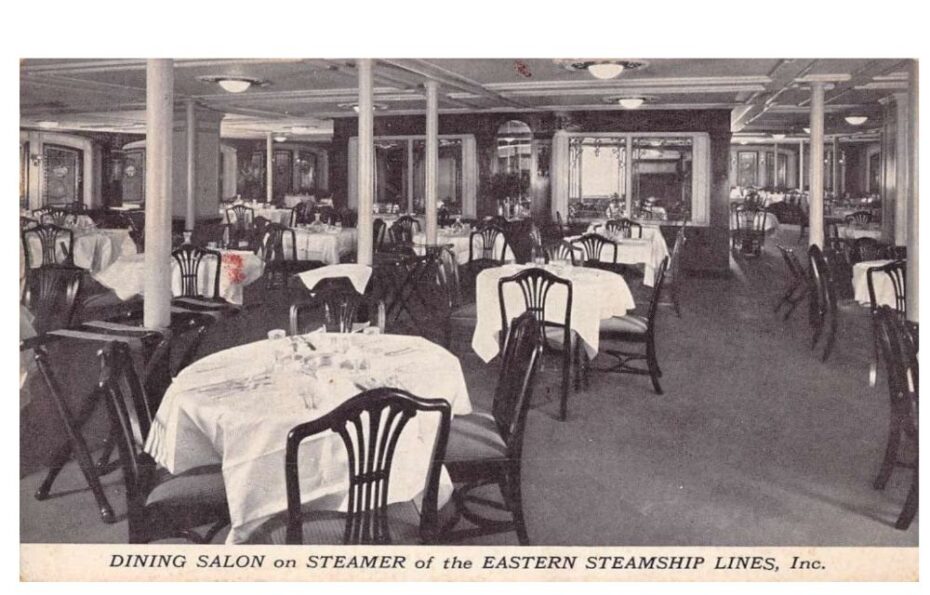

Built in 1900, the SS City of Rockland was a paddle driven luxury steamer, the queen of the fleet of the Eastern Steamship line, that would carry 2,000 passengers from Boston to Maine in the height of elegance. Described by the Bangor Daily News as, “she’s as handsome as she’s able – she’s a palace set afloat, with her electric lights, she races up and down the coast.” Unluckily, the steamship was as much known for her beauty as her tendency to be accident prone. During twenty three years of service, she collided with multiple ships, partially sank whilst moored in Boston, and ran aground in the shallow waters between Little and Great Misery Island, where she burned to the waterline and where her ruins can still be seen at low tide.

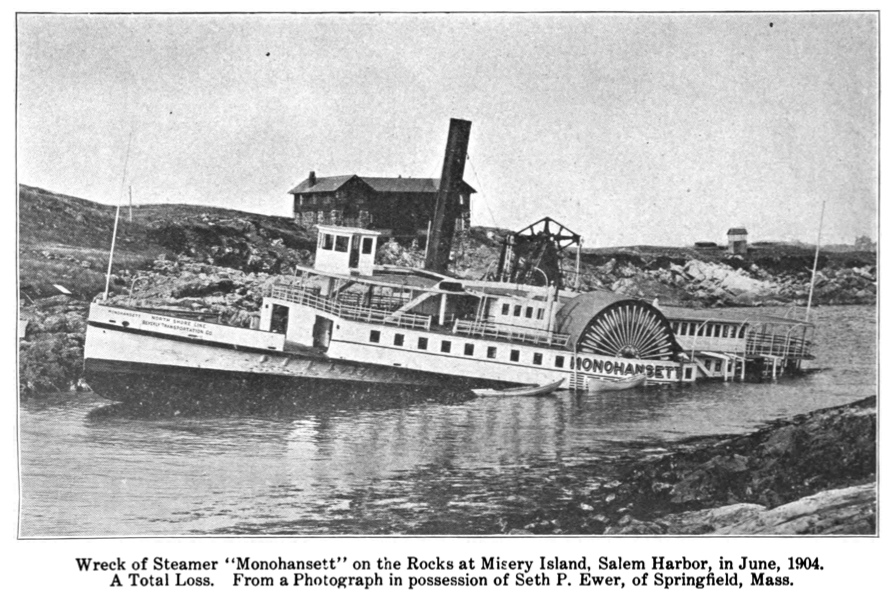

Other pleasure ships also fell foul of the wild and rocky coastline of Salem Sound. In 1904 another steamer, the Monohanset, was making for Salem Willows, a Victorian holiday resort of carousels, hotels and arcades north of the city, when in thick fog, she was wrecked on the rocks of Misery Island. One of the most famous vessels to ply her trade from Nantucket Sound to Maine, she had been built in the second year of the Civil War with deck timbers of white oak and chestnut, and was a particular favourite of General Grant. The Vineyard Gazette reported of the stricken ship, “so complete was her self-destruction that there was nothing left for her last owners to do but strip her fittings and set fire to her hulk. Then she blazed out a defiance from her funeral pyre and died like a good ship. She was the Monohanset.”

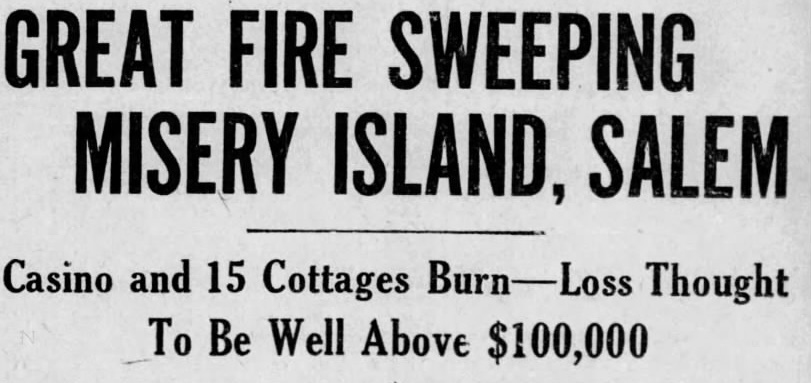

A similar fate would soon befall the holiday resort on Misery Island. With preparations underway for the summer season of 1926, the island’s lone caretaker started a small brush fire that swiftly ravaged the casino and cottages. With the nearest fire department a half hour’s sail away, the buildings were swiftly destroyed. The Boston Globe reported how the island, “was smothered in a blanket of fire, as the tongues of flame leapt thirty feet in the air….it was one of the most spectacular sights ever seen along the North Shore, and from the mainland it appears that the flames are leaping from the edge of the water.”

A century later, the island remains uninhabited. What is curious is that two nautical miles southeast an island of similar size and history is thriving. Baker’s Island is principally a summer colony of grand private mansions and homes, resplendent in comparison to the ruins of its neighbouring Misery Island. At one point in the 1930s, plans were threatened to build a sewage treatment plant on Misery Island, that would have forever destroyed its natural beauty and wilderness. The island was saved by the Trustees of Reservations, a non-profit land conservation and historic property organization dedicated to protecting natural and historical gems in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

Today, Essex Heritage another non-profit organization that protects the local heritage and owns an 18th century lighthouse on Baker’s Island will sail you on their landing craft, the Naumkeag to both Baker’s Island where you can spend the night at the lighthouse property, or to the uninhabited Great Misery Island. “We think it’s the mix of maritime culture and coastal ecology that makes these islands so inviting,” explain Essex Heritage. “Woodlands, maritime thickets and the open meadows….terrific coastal panoramas, rocky overlooks….watch shorebirds skitter just about the surf, then allow your gaze to drift outward and eastward to the ocean horizon.” The days of cocktail parties and lawn tennis might have long departed Great Misery Island, but there remains a remote, uninhabited gem lying off the coast of Salem Sound with a natural beauty that is far from miserable.