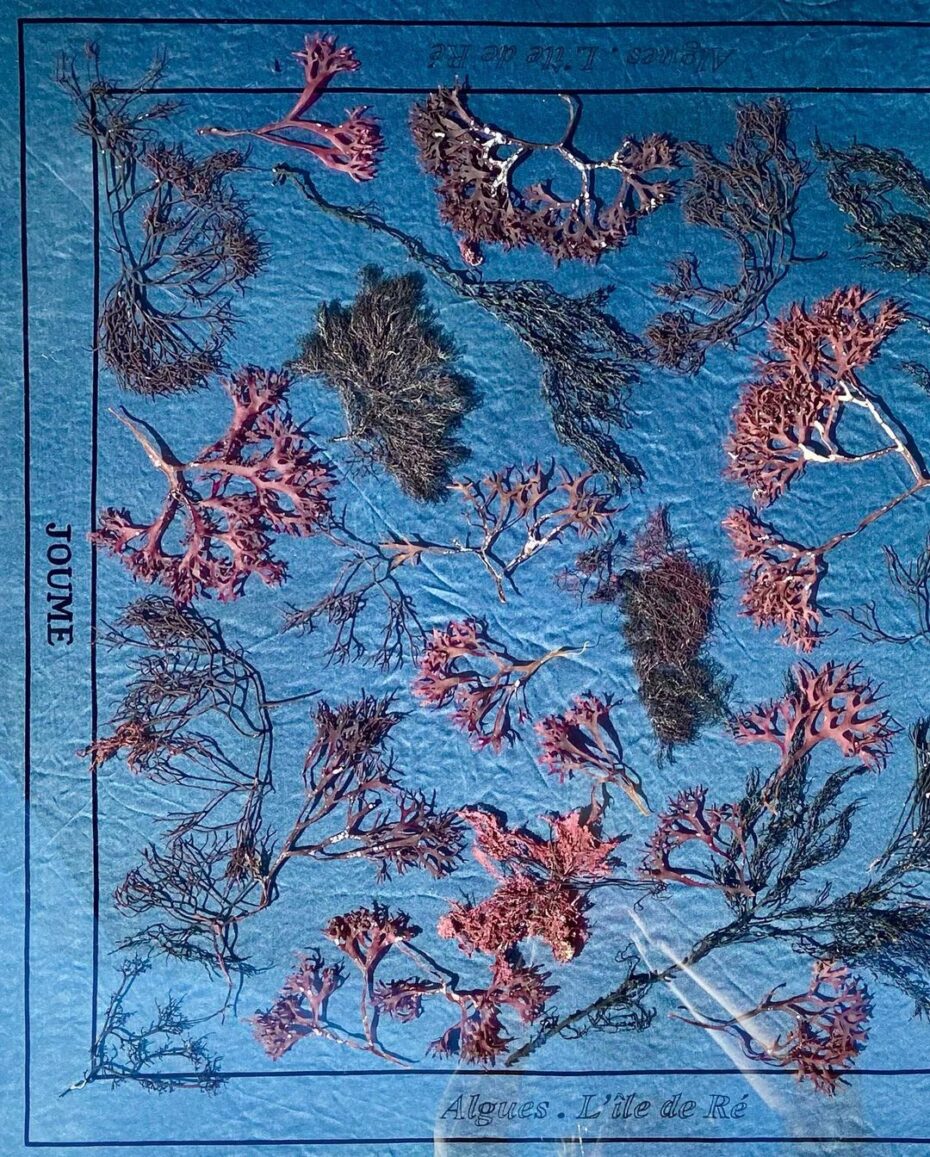

There’s something in the window of my boutique on Paris’ Left Bank that has been stopping wanderers in their tracks. It’s that mesmerising shade of deep Prussian blue, the result of a 19th-century photographic process known as cyanotype, once favoured by Victorian botanists and early female pioneers of photography. Today, cyanotype has found a second life among today’s young creators, one of whom I happened to meet on an island on the west coast of France this summer. Parisienne, Alice Fraudeau, has been breathing fresh air into an age-old technique with her beguiling cyanotype scarves, made by hand, featuring vintage-inspired animal anatomy. I was immediately taken with her creations, and I’m now extremely proud to be the first stockist of her line, Atelier Joume. Naturally, this calls for a little dive into the lost world of cyanotype….

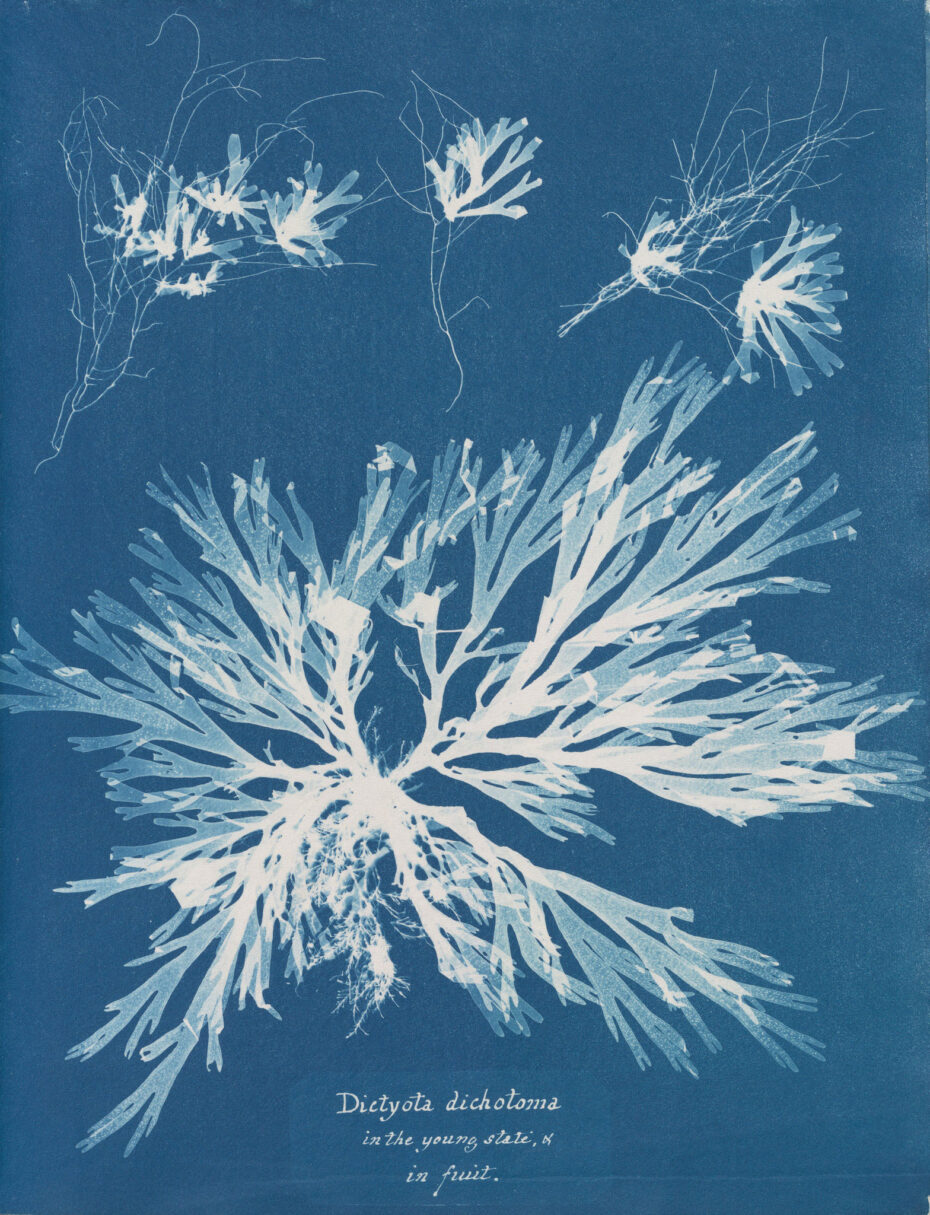

The cyanotype is a technique steeped in a fascinating history of scientific discovery, creative rebellion, and feminist artistry. The process was invented in 1842 by Sir John Herschel, an English scientist, but it was Anna Atkins — an amateur botanist and friend of Herschel — who made cyanotype famous. Atkins used the process to create detailed botanical illustrations, becoming the first person to publish a book with photographic images. Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions is considered the first-ever photo book and cemented Atkins as a pioneer in both photography and science, though she wasn’t given due credit until much later in history.

In a time when photography was largely a male-dominated field, Atkins’ use of cyanotype allowed her to sidestep the complicated, expensive processes that her male counterparts favoured. Instead of producing traditional portraits or landscapes, Atkins focused on plant life. By laying seaweed, ferns, or other organic materials directly onto chemically treated paper and exposing it to sunlight, she created ghostly, ethereal silhouettes in striking blue. Her work was not only visually stunning but also served a scientific purpose, documenting plants in exquisite detail.

Cyanotype offered a way for women in the Victorian era, largely excluded from both art and science, to contribute meaningfully to both. In fact, many women of the era were drawn to the cyanotype process for its accessibility, and, perhaps, for its inherent subversion of traditional photographic practices. Without the need for expensive equipment or chemicals, it was an artistic rebellion of sorts, quietly staged in back gardens and drawing rooms.

There’s something delightfully analog about cyanotype that feels like an antidote to our fast-paced, digital world. It’s a process that demands time, patience, and just the right amount of sunlight. At its core, cyanotype is tactile and organic. No two prints are the same, and that’s part of the charm. The process, which involves placing objects or transparencies on treated fabric or paper and exposing them to sunlight, invites the artist to work alongside nature. It’s slow, imperfect, and refreshingly free of technology — qualities that resonate deeply with young artists like Alice, who are eager to reconnect with tangible, handmade processes. There’s something almost magical about watching an image slowly emerge under the sun’s rays, a reminder that some of the most beautiful things in life can’t be rushed. Cyanotype also speaks to the larger “slow fashion” and “slow design” movements rejecting mass production and embracing craftsmanship, individuality, and sustainability.

The deep indigo blues and soft, faded edges of cyanotype prints are the perfect blend of minimalism and drama, and there’s an irresistible pull toward the medium’s old-world beauty. All the right ingredients for something I like to keep in my Cabinet.