In an age where our phones hold thousands of photos and the concept of “keepsakes” feels increasingly digital, it’s easy to overlook how people once cherished tangible, tiny ways of keeping their memories close. But step back in time to the 1850s, and you’ll find a quirky, ingenious invention that combined science, art, and sentimentality: René Dagron’s stanhope. A microscopic marvel tucked into lockets, rings, and even letter openers, this invention allowed people to peer through a tiny lens and behold a whole world—a photograph so minuscule it could fit on the head of a pin. Let’s take a closer look at how this little gem of an invention captured the imaginations—and the hearts—of people over 150 years ago.

Dagron patented the stanhope in 1857, naming it after Sir Charles Stanhope, an 18th-century optics pioneer whose lenses inspired his innovation. Dagron’s genius was in his ability to miniaturize photography to the point where entire scenes, letters, or even books could fit into a device no bigger than a charm.

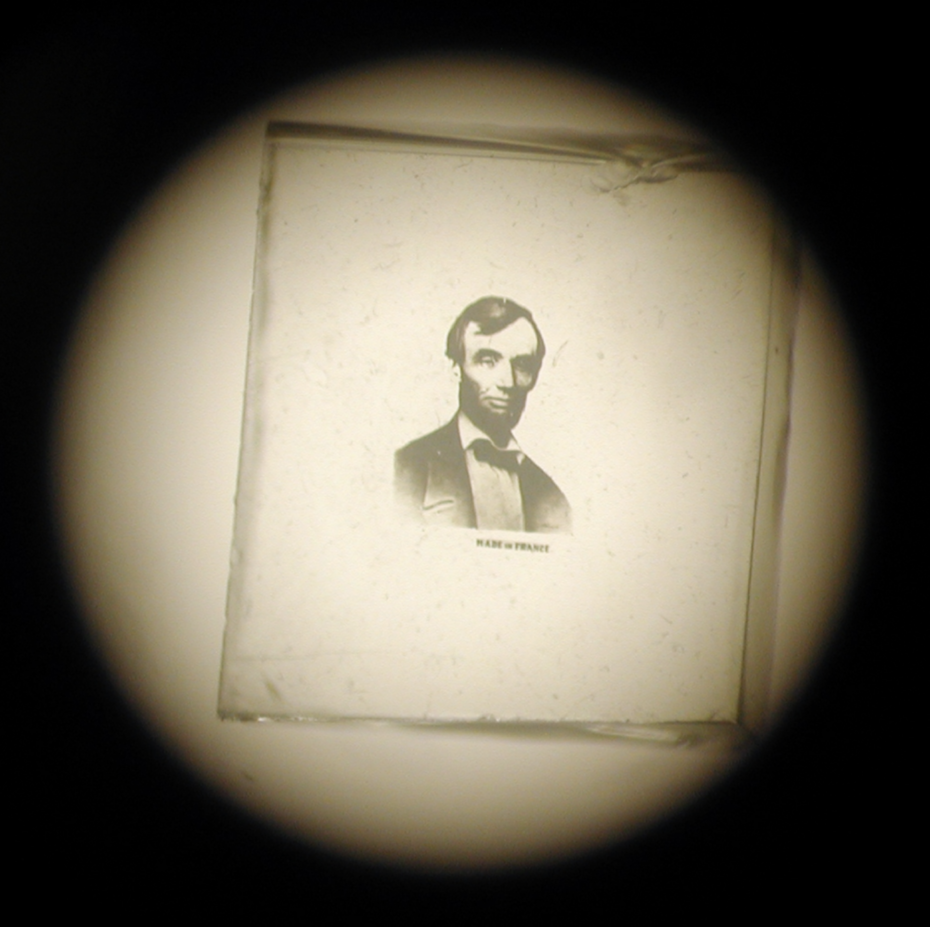

By embedding a tiny cylindrical lens into objects such as jewellery, letter openers, and souvenirs, Dagron made it possible for the wearer or owner to peer into the past through an optical wonder. Look through the lens, and an astonishingly detailed image would appear, magnified and illuminated by nothing more than natural light.

8mm / 31. in

These stanhopes — or stanho-scopes, as they were sometimes called — became a sensation. Jewellery adorned with microphotographs was particularly popular, ranging from lockets and cufflinks to rings and pendants. But Dagron’s creations were not limited to jewellery.

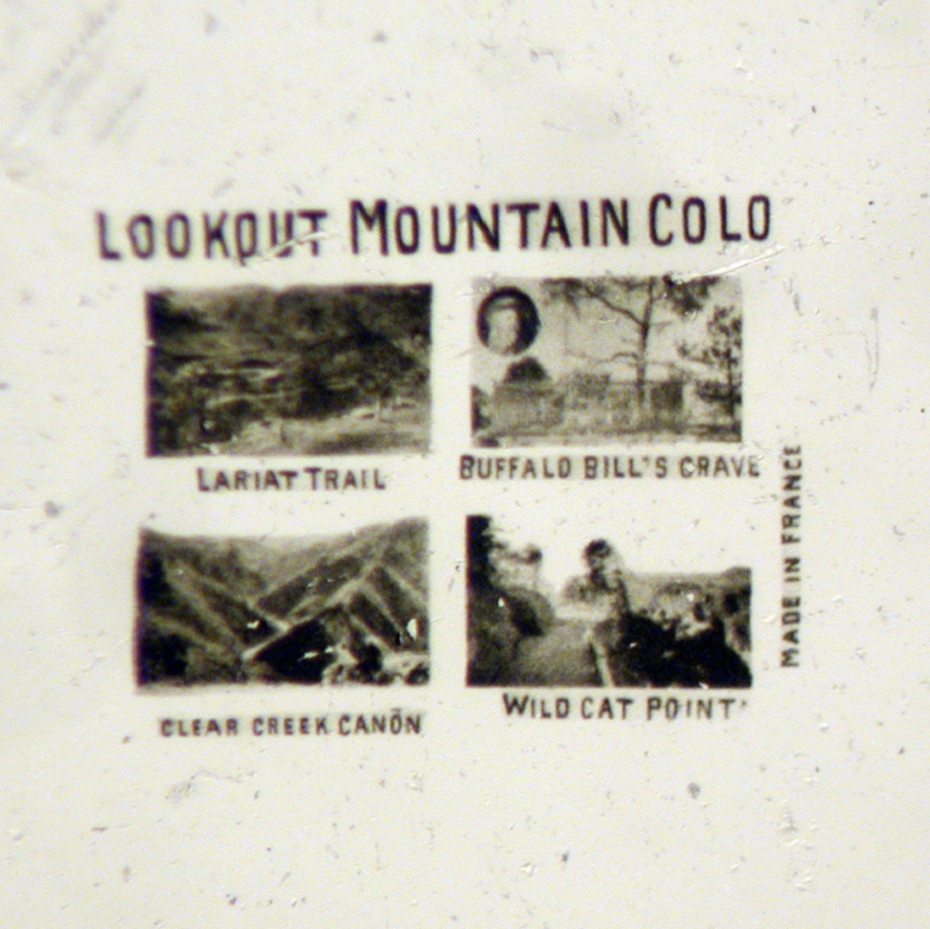

He incorporated stanhopes into all sorts of everyday objects — pipes, thimbles, and even walking sticks. For travelllers, souvenirs embedded with stanhopes offered miniature glimpses of famous landmarks, creating an early form of photographic mementos that predated postcards.

Dagron’s success hinged on the burgeoning art of microphotography, a delicate process of shrinking photographs to an almost unfathomable scale. Using photographic plates, he could capture images and then reduce them to the size of a pinhead. These miniature masterpieces were inserted into the end of a lens, allowing viewers to marvel at the microscopic detail without specialized equipment. The stanhopes became a popular method for preserving sentimental images, such as family portraits or love letters. They also served as discreet vessels for political propaganda, hidden messages, or secret codes during times of war—a sort of James Bond gadgetry for the Victorian era.

While the invention was revolutionary in its time, the popularity of stanhopes waned with the advent of modern photography and the rise of mass-produced souvenirs. Yet, these tiny optical marvels of course still hold a certain charm for collectors and history enthusiasts. Each one tells a story—both in its craftsmanship and in the images it conceals. A stanhope locket might hold a photograph of a long-lost loved one, while a thimble might offer a view of the Eiffel Tower circa 1900. Today, antique stanhopes are coveted by collectors who appreciate the quirky ingenuity of Dagron’s invention.

René Dagron’s microscopic photo-jewellery is a testament to the Victorian fascination with miniaturization and his invention not only brought photography into the realm of personal keepsakes but also introduced a playful element to the way we view and share images.

Dagron’s invention wasn’t just clever — it was profoundly human. These tiny optical devices were designed to hold the most intimate moments and secret messages, to be hidden in plain sight, and to offer a sense of wonder that feels just as enchanting today as it must have in the Victorian era. They embody the spirit of an era when science and sentimentality intertwined, creating objects that were both functional and deeply personal. So the next time you encounter a vintage charm or souvenir with a mysterious lens embedded in its surface, take a closer look — it might just hold a tiny world within.

If you’re curious about collecting some, you’ll want to start with the expert, MW Sheibley, who can also restore, repair and create custom stanhope lenses.

Further viewing: