Gather ‘round, cinema enthusiasts, because it’s time to tip our top hats to one of vintage Hollywood’s most dazzling visionaries: Busby Berkeley. A man whose name conjures up images of synchronised swimmers, overhead shots of geometric dancers, and the kind of glitzy, glittery choreography that could put a magpie into cardiac arrest. Berkeley didn’t just direct; he orchestrated, and in doing so, he transformed the way we experience musicals on the silver screen. Let’s dive into his kaleidoscopic world—sparkles, synchronised legs, and all.

First, some Busby basics. Born in 1895, Berkeley William Enos (yes, that’s his real name—don’t let it dull the sparkle) grew up in showbiz. His mother was an actress, and it wasn’t long before Berkeley caught the theatre bug himself. After serving in World War I, where he honed his knack for organising troops into impeccably choreographed drills, he found his way to Broadway, and later, to Hollywood during its glitter-drenched Golden Age.

Berkeley’s entrance into the film world in the 1930s coincided with the birth of the movie musical. Studios like Warner Bros. were cranking out musicals faster than you could say “Jazz Hands,” but audiences were growing tired of the same ol’ song-and-dance routines. That’s when Berkeley swooped in like a sequined saviour, shaking up the genre with his unique flair for theatricality and visual spectacle.

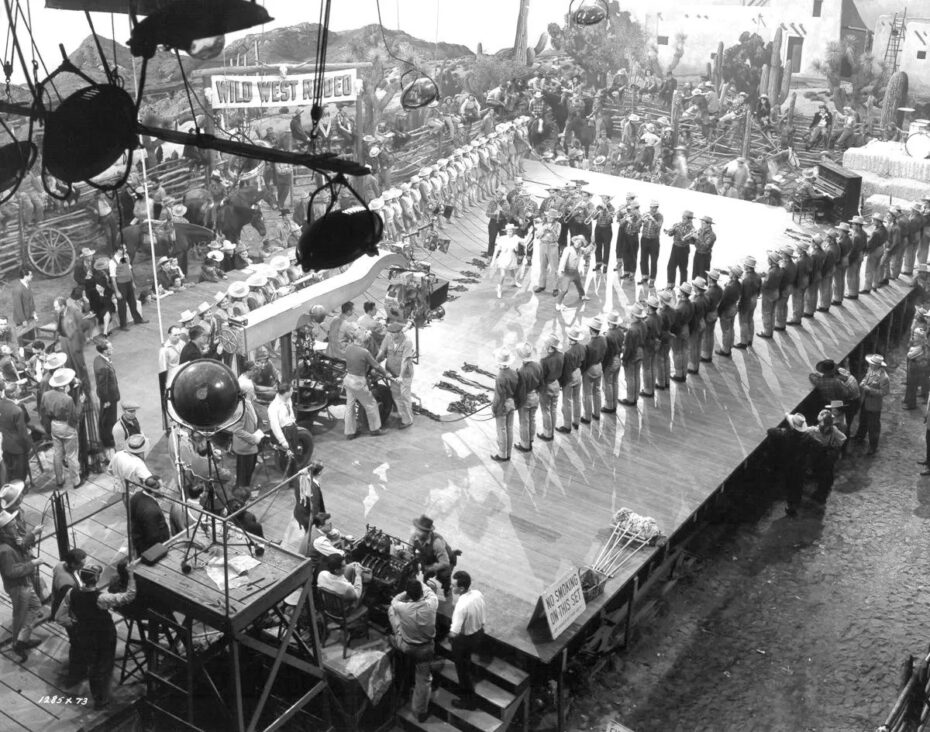

What set Berkeley apart from other directors and choreographers of his time was his ability to think beyond the stage. Most musical numbers of the era were shot as if the audience were sitting in the front row of a theatre — static and a little stale frankly. But Berkeley asked himself, Why should the camera be tied to the ground? Let’s make it dance too!

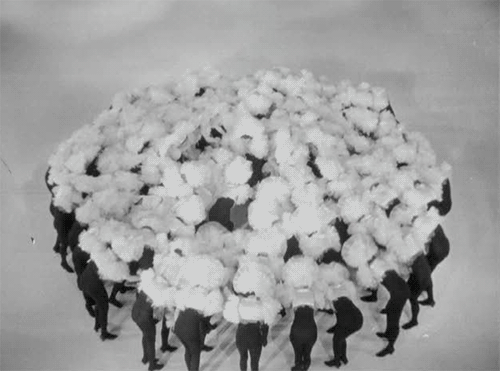

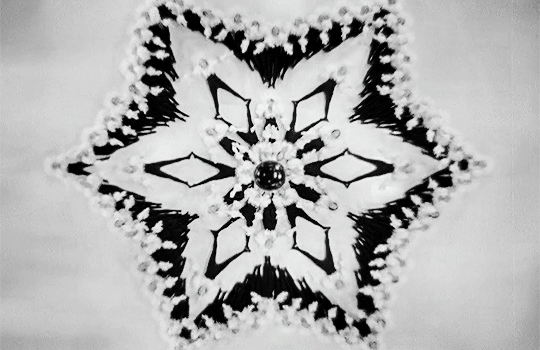

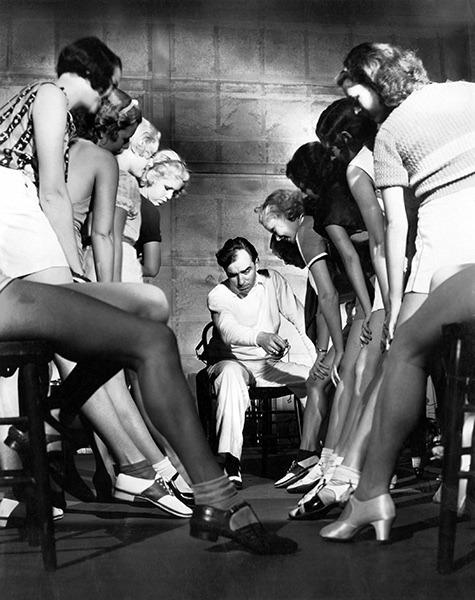

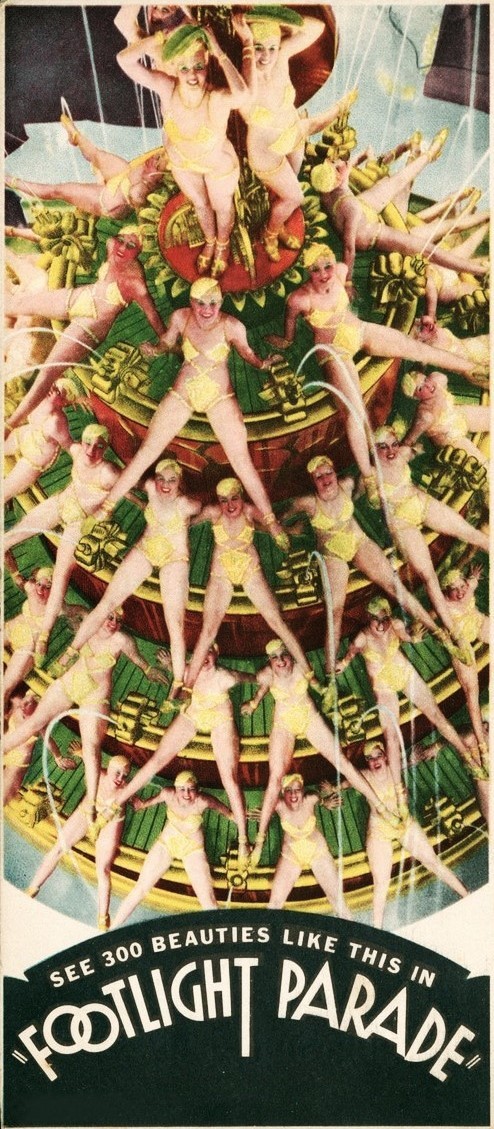

Cue the crane shots, the swirling camera movements, and, of course, the kaleidoscopic overhead sequences that became his signature. Berkeley would arrange dancers into intricate patterns—think human snowflakes, art deco mandalas, and flowers blooming into synchronised high kicks. Then he’d capture it all from above, turning choreography into visual art.

Way ahead of his time (before CGI of course), he did special effects that people still can’t figure out. His shots were so mesmerising that they could almost make you forget there was an actual plot happening somewhere in the background.

Berkeley’s films were like art deco fever dreams. They didn’t just entertain; they hypnotised. His creative process was as unconventional as his work. Legend has it he didn’t even choreograph dances in the traditional sense. Instead, he would sketch out his ideas geometrically, as though he were designing a living, breathing mosaic.

Some of his most famous creations include:

“Footlight Parade” (1933):

the jaw-dropping “By a Waterfall” sequence, complete with dozens of synchronized swimmers forming patterns in a giant pool? Esther Williams owes her entire career to this single scene:

“42nd Street” (1933):

The backstage musical to end all backstage musicals. The climactic title number was a riot of dancers moving in perfect harmony, framed by Berkeley’s signature overhead shots:

“Gold Diggers of 1935”:

This is the one where he out-Berkeley’d himself with “The Lullaby of Broadway” sequence—a 14-minute mini-movie featuring a cavalcade of dancers cascading through a dreamscape of staircases and glittering chandeliers:

Berkeley’s innovations weren’t without their challenges. His extravagant vision often clashed with studio budgets, and his perfectionism sometimes pushed his dancers to their limits (there’s a reason they coined the term “Busby Berks”). But the results? Pure movie magic. Audiences left theatres dazzled, dreaming of gold sequins and synchronized swimming pools.

Despite his success, Berkeley’s career dimmed after the 1940s, as tastes in cinema shifted and war-time realism replaced his fantasy-filled spectacles. But his influence on the musical genre — and on cinema as a whole — has never faded. Directors like Esther Williams and even the technicolor-loving Baz Luhrmann owe more than a passing nod to Berkeley’s kaleidoscopic vision.

Today, watching a Busby Berkeley number feels like stepping into a dream — a dream where geometry, glamour, and glitter collide in perfect harmony. His work reminds us that movies don’t just tell stories; they transport us, delight us, and occasionally leave us a little dizzy. In a world that could always use more sparkle, Berkeley’s vision continues to twirl on, overhead cameras and all.

“In an era of breadlines, depression, and wars, I tried to help people get away from all the misery . . . to turn their minds to something else. I wanted to make people happy, if only for an hour.”