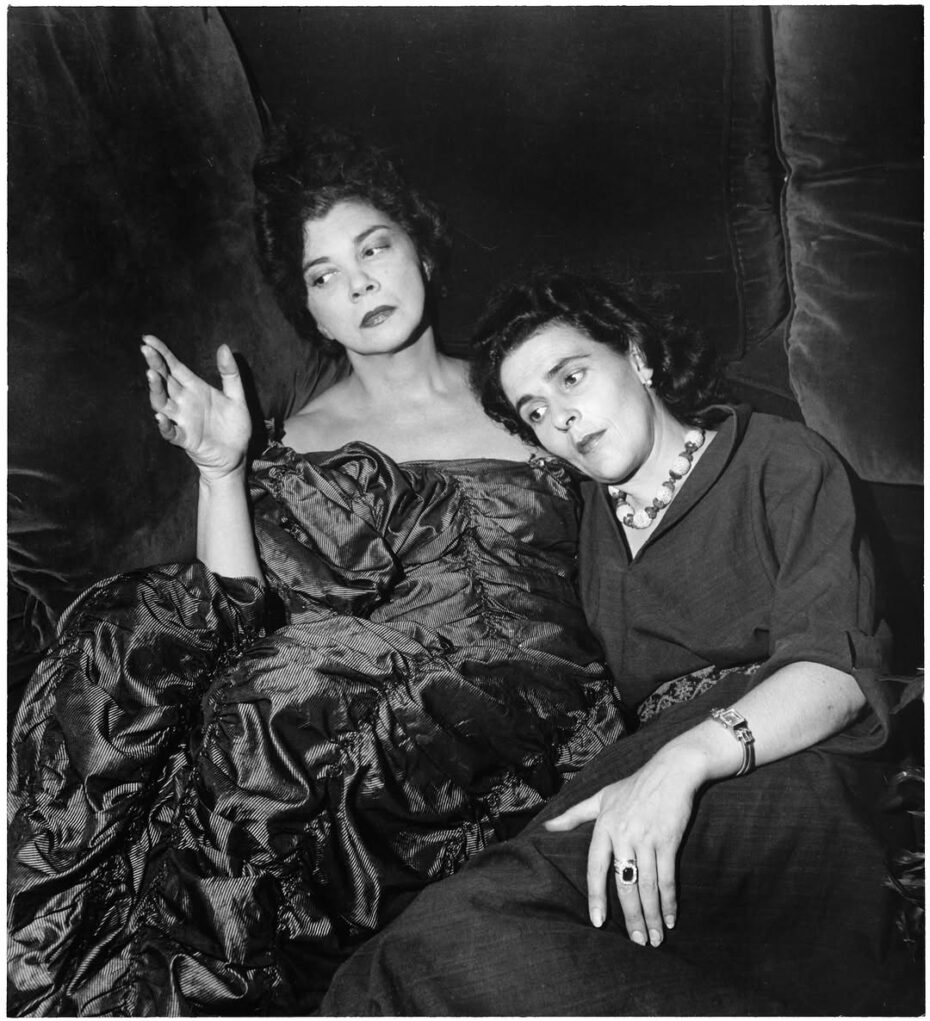

Leonor Fini and Leonora Carrington are familiar names around here. We’ve posted about each of these women separately (familiarise yourself with Carrington here) and Fini is one of my personal favourite bohemians of the 20th century. But then I stumbled upon an old photograph which pictured them together in Paris and it stopped me in my tracks. They were friends? As it turns out, very much so. Thanks to recent scholarship shining a light on the cultural and historical significance of Surrealist women, many more of us are aware of these two artists as key women in the movement, but their personal connection and collaborative spirit remain less discussed. And while we might be quick to reference historical “bromances” like Dali and Man Ray or Hemingway and Fitzgerald, equally transformative friendships formed by women tend to be quietly overlooked. Linked primarily by their gender within what was primarily a male-dominated group, Fini and Carrington actually forged a genuine camaraderie based on mutual respect, intellectual curiosity, and a love of the fantastical. This friendship was no doubt strengthened by a shared defiance: neither woman wanted to be cast in the role of ‘muse’ to male artists, nor subsumed by the Surrealist movement’s sometimes limiting definitions of femininity and creativity. And when is it not a good time to highlight the importance of female allyship?

During the late 1930s and early 1940s, Paris was the epicenter of Surrealism—a crucible for experimentation and rebellion where artistic personalities converged from across the globe. Within that vibrant cultural terrain, Leonor Fini and Leonora Carrington found each other, forging a bond that went beyond the typical salon acquaintance. Carrington, newly arrived in the city, was quickly pulled into the Surrealist orbit through her relationship with Max Ernst, while Fini was already an established figure with her own circle of friends and patrons.

Fini’s apartment near the Boulevard Montparnasse was famously filled with cats, exotic costumes, and a parade of curious artifacts—testaments to her fascination with the esoteric and theatrical. Carrington, similarly drawn to myth and magic, found in Fini someone with whom she could openly share her visions of feminine power, shapeshifting creatures, and dream logic.

Alongside their fellow Surrealists, they attended exhibition openings and private soirées—sometimes hosted by patrons like Peggy Guggenheim—where the latest Surrealist manifestos were debated and new works unveiled. Yet, while many of their male peers jockeyed for central influence under André Breton’s strict ideas on “pure” Surrealism, Fini and Carrington were more interested in subverting rigid doctrine.

Though often described simply as “female Surrealists,” both Fini and Carrington had complicated relationships with Surrealism. They embraced certain core ideas, like tapping into the unconscious, subverting reality, and celebrating the bizarre, but each had reservations about the movement’s more restrictive or dogmatic elements. They both shared an interest in magic, alchemy, and esoteric symbolism—elements that appear frequently in their work. Their depictions of surreal, otherworldly spaces peopled by hybrid creatures and powerful feminine figures speak to both artists’ fascination with the hidden realms of the human psyche. This artistic common ground provided fertile soil for mutual inspiration and critiquing each other’s work.

One of the lesser-known facets of the Fini-Carrington friendship is their engagement with theatre and costume design. Both artists ventured into set and costume design at different points, drawn to performance’s transformative power. In 1940s Paris, the Surrealist stage was an important cross-disciplinary space, bringing visual art, literature, and performance together.

Although their theatrical projects did not always involve direct collaborations, they exchanged ideas about how to merge Surrealist aesthetics with live performance — how to evoke the atmosphere of a dream, or how to manipulate lighting, color, and form on a stage.

The friendship between Fini and Carrington was also evident in how they portrayed women, particularly themselves, in their art. Both painters broke free from the passive model of the female subject; instead, they depicted women as active, mysterious, empowered, and often accompanied by animal figures acting as protectors or extensions of their inner selves. Scholars have noted how Carrington’s shapeshifting horse-women and Fini’s sphinxlike femmes fatales or half-feline creatures suggest a reclamation of mythic and occult power for women. Their friendship encouraged each woman to explore new symbolic languages without fear of reproach.

The dynamic between these two challenges long-standing narratives about collaborative influence in the movement. The Surrealist mileu was a competitive space, and their spirit of camaraderie set them apart from some of their more competitive male counterparts. In the face of a Surrealist environment that could be both welcoming and alienating, the two artists found in each other an ally: someone to experiment with, to dream alongside, and to disrupt artistic norms together. Their bond, often relegated to footnotes in broader Surrealist discussions, warrants a closer look for what it reveals about the power of women’s friendships to shape modern art.

Even amid the outbreak of World War II, which eventually forced Carrington to flee Europe, the two artists maintained a kinship that had been cemented during those formative Paris years. In the city’s vibrant, if sometimes fractious, avant-garde community, Fini and Carrington’s mutual enthusiasm—and their willingness to nurture each other’s unconventional visions—stands out as a powerful model of female camaraderie and creative exchange. Their relationship represents more than a historical curiosity. In today’s climate—where patriarchal norms seem to be resurging and women’s autonomy is under increasing threat—Fini and Carrington’s friendship resonates more powerfully than ever. Their alliance underscores how mutual support and shared defiance can embolden women to create and live on their own terms, despite external attempts to constrain them.