Unicorns have officially invaded what was once our fairly stylish Parisian living room. My nearly-three year-old daughter twirls in a fluffy unicorn costume, her laughter filling the room as she chases her brother with a bubble-blowing toy shaped like a rainbow-maned mare. How did we get here? I started wondering lately. The unicorn, once a creature of medieval allegory and aristocratic heraldry, now reigns over a pastel-colored empire of lunchboxes, animated series, and birthday party themes. Putting my own parental shortcomings aside, this scene, and my daughters current obsessions with unicorns, is the culmination of a centuries-old myth’s transformation —from a symbol of sacred purity to a ubiquitous emblem of childhood wonder. But how exactly did this mythical beast gallop from the pages of ancient bestiaries into the hearts of modern children? As I walked to the checkout counter at the bookstore this morning, clutching unicorn wrapping paper, a unicorn puzzle and a rainbow unicorn stuffed toy, I was curious.

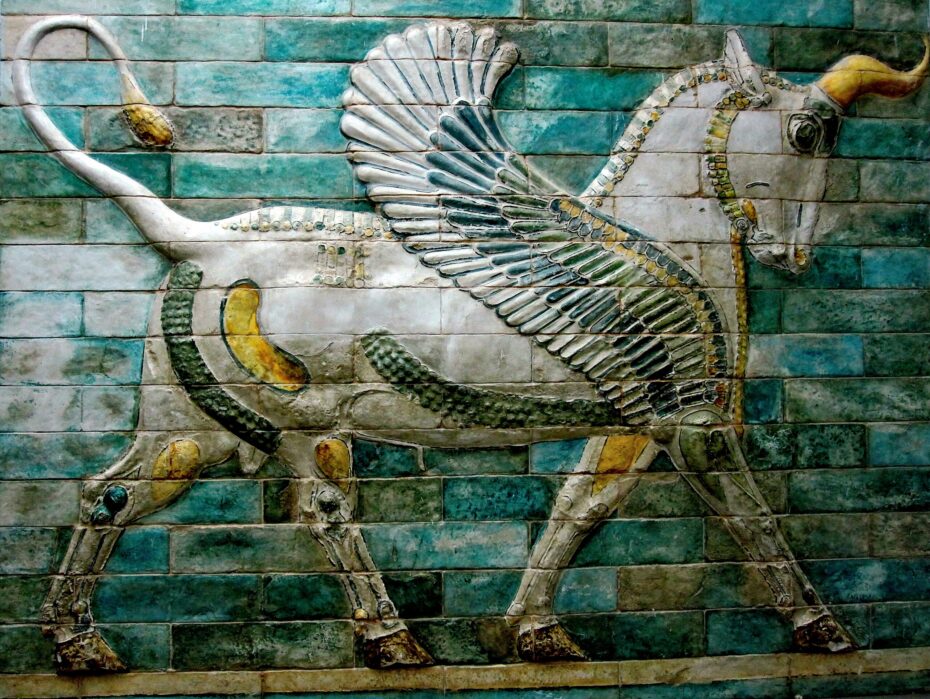

The unicorn’s origins are anything but child-friendly. First described by the Greek physician Ctesias in the 4th century BCE as a fleet-footed, single-horned ass, it evolved in medieval Europe into a potent Christian symbol — a pure creature only tamed by virgin maidens, often allegorized as Christ himself.

Ctesias sspoke of the “monoceros”: a startlingly rare creature believed to roam the distant realms of India or Ethiopia. These mentions, entwined with travelers’ tall tales, were enough to capture Europe’s imagination. While Greek naturalists debated the creature’s provenance, the unicorn had already begun its slow ascent into legend.

Fast-forward to medieval Europe, where bestiaries — lavish, illustrated compendiums of real and mythical animals — cemented the unicorn’s image as a horse-like creature with a single spiraling horn. In those centuries, it became more than a curio; the unicorn was emblematic of purity, often linked to religious iconography. In tapestries like “The Unicorn in Captivity,” a fifteenth-century masterpiece that now resides at The Met Cloisters in New York, the animal was draped in Christian allegory and regal symbolism. This elusive being, captured by the faithful, was a representation of incorruptibility in a corruptible world — quite a leap from the cartoonish, rainbow-maned creature we see frolicking across backpacks today.

The famed Hunt of the Unicorn tapestries, woven in the late Middle Ages, depicted its capture and slaughter, a metaphor for divine sacrifice. “For centuries, the unicorn was a serious, even tragic figure,” explains Dr. Eleanor Vane, a cultural historian at Oxford. “Its blood was thought to cure ailments; its horn, a talisman against poison.”

In the Renaissance, the unicorn bounded beyond religious allegory. Scotland officially embraced it as a national symbol, an indication of the creature’s revered status. Heraldic uses carried the aura of nobility and power; the unicorn was not simply an animal of enchantment but a signifier of virtue and, at times, fierce independence. Centuries on, the Scottish coat of arms still features the unicorn (although, one might surmise, not in the lilac and glittery form of modern children’s marketing).

During the Enlightenment, serious-minded scientists and philosophers took a skeptical view of the unicorn, relegating it to the realm of improbable myths. Yet the legend persisted in folklore and fairy tales, passed along by traveling storytellers and local legends. The idea of a magical horse was too enthralling to be so easily dismissed. With each retelling, the unicorn’s image became gentler, more accessible, and—dare we say—cuddlier.

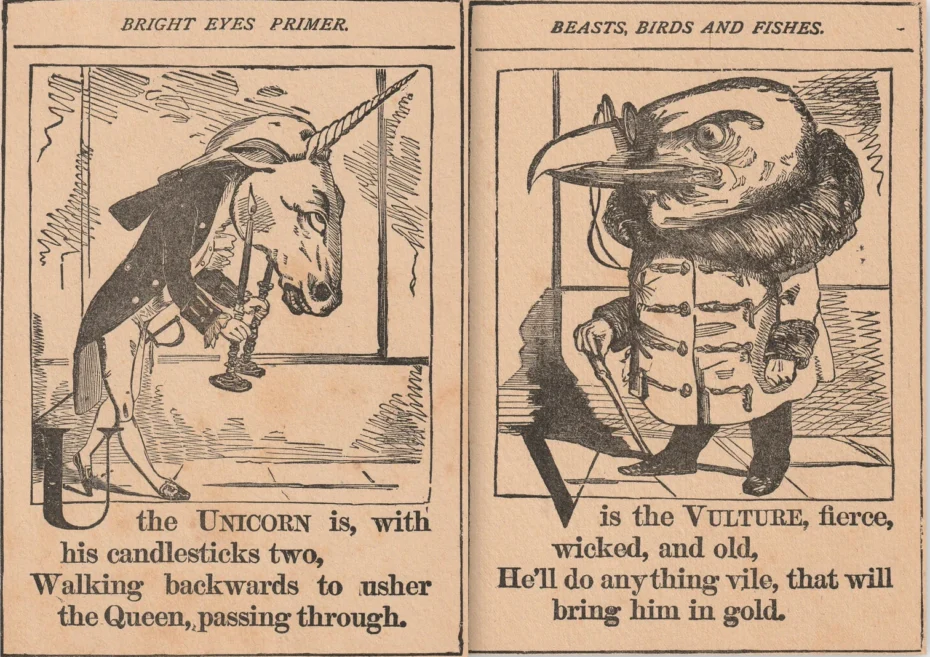

By the 19th century, the unicorn began shedding its solemnity. Victorian fairy tales and whimsical literature, such as Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass (1871), recast it as a creature of fantasy, albeit still peripheral. The real metamorphosis, however, began in the 20th century, as the unicorn trotted into the playground of pop culture.

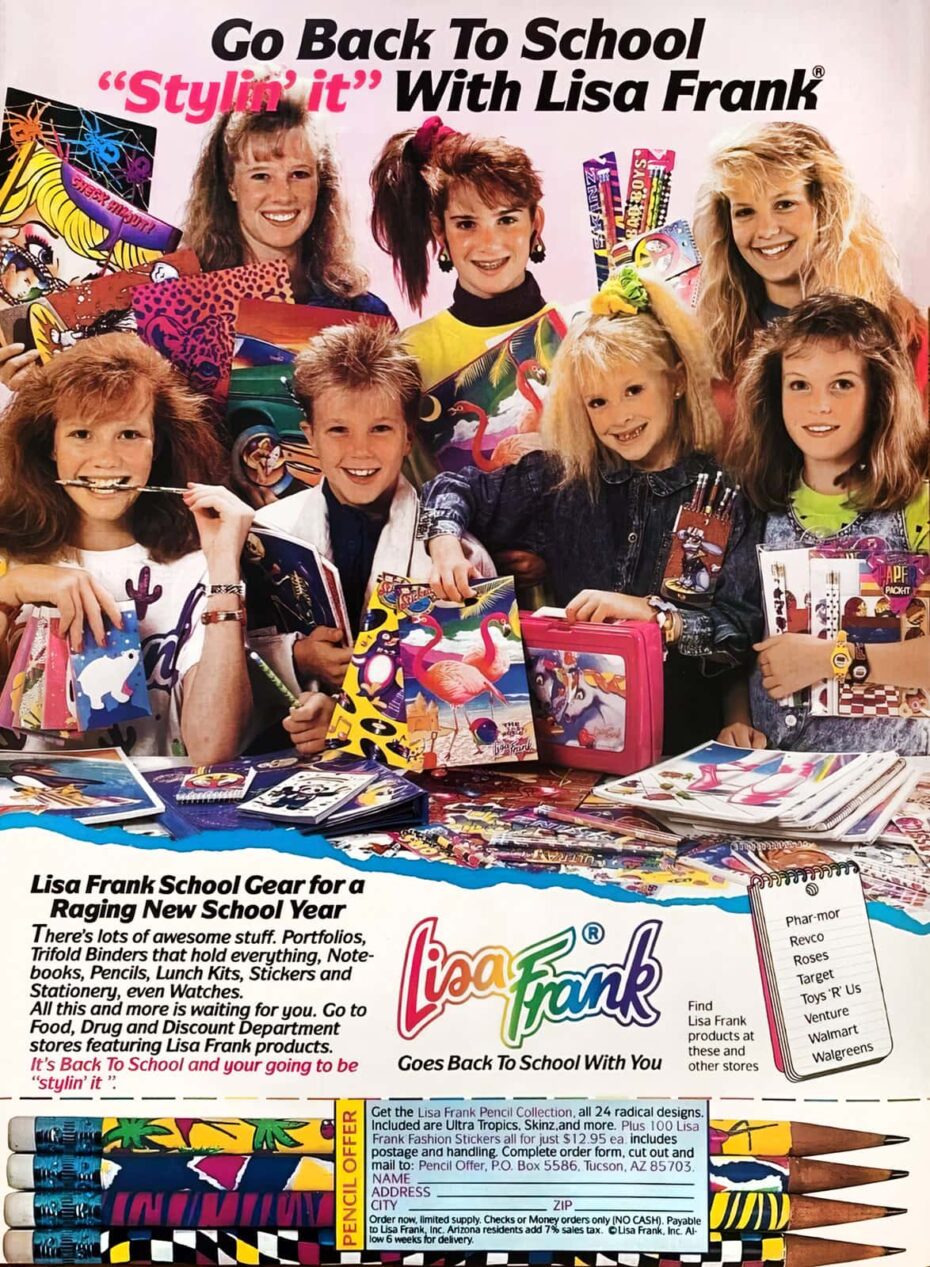

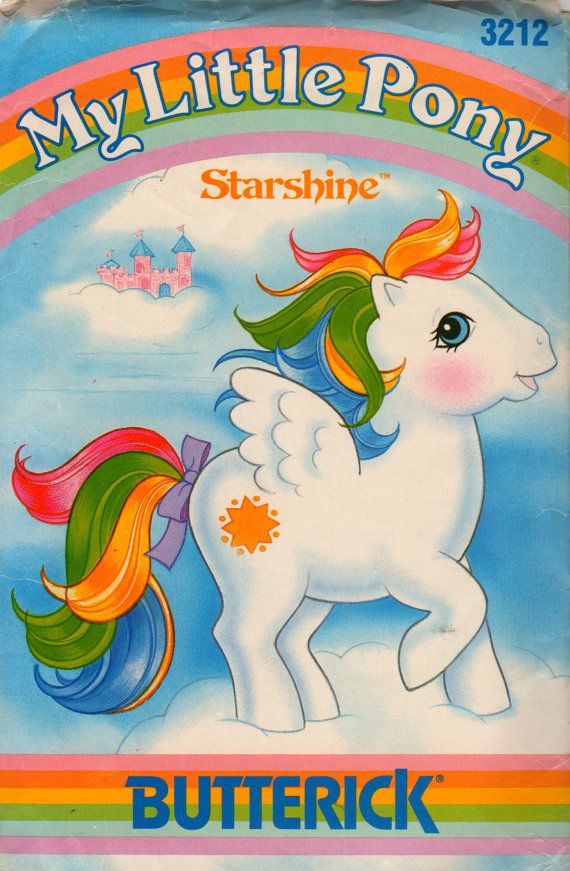

If the unicorn retained a faintly medieval aura through the Victorian era, it found a whole new life in the latter half of the twentieth century. Two phenomena helped plant the unicorn firmly into kids’ hearts: My Little Pony—with its sweet, big-eyed equines, some of whom sported single horns—and Lisa Frank’s stationery empire, which teamed kaleidoscopic color schemes with a menagerie of smiling animals. The Lisa Frank unicorn, always rendered in swirling rainbow hues and surrounded by hearts or stars, sealed the creature’s pastel destiny and would forever link the creature to a kaleidoscope of cheerful hues.

“It wasn’t about sacredness anymore — it was about friendship, sparkle, and accessibility,” says toy historian Miriam Linford. “My Little Pony democratized the unicorn.” Meanwhile, film and television had its hand in popularizing the modern unicorn mythos. A wave of fantasy movies—from “Legend” in 1985, featuring a resplendent white unicorn, to animated features—showed the creature as a benevolent force, often with healing powers or the key to saving enchanted realms. These depictions, while whimsical, preserved some of the ancient aura of mystery, blending it with the childlike wonder that has become the unicorn’s hallmark.

In the age of social media, the unicorn reached new and dazzling heights. By the 2010s, “unicorn” described not only the magical beast but also a host of “rare” phenomena. Tech startups aspiring to billion-dollar valuations became “unicorns.” Specialty cafés began peddling “unicorn lattes” topped with pastel foam and sprinkles. Fashion lines boasted “unicorn hair” in shimmering, iridescent dyes. The children’s market naturally followed suit, doubling down on all things sparkly. The range of unicorn toys and accessories exploded: from sequined T-shirts to interactive robotic pets that light up and sing.

What’s particularly telling is how the unicorn has integrated itself into the daily life of children — and, by proximity, the adults who shop for them. Birthdays are no longer complete without a “magical unicorn” piñata or a rainbow-horn cake. More than ever, entire aisles at supermarkets seem devoted to unicorn-themed plates, cups, and party favors. On social media, proud parents share snapshots of their toddlers dressed in unicorn-themed outfits, with horns perched on headbands and manes of tulle trailing behind them. The once secretive, near-mystical creature has become the face of childhood entertainment, its mysticism transformed into a pastel fantasy.

So why did the unicorn — rather than, say, the dragon or the griffin — become the go-to emblem of enchanted innocence? Well, it’s got great brand identity. The unicorn is a strange mash-up of the familiar and the fantastical. Children understand horses, and a single horn can read as just enough magic to spark wonder without inducing fear. The creature’s visual simplicity, for marketers, is a dream: a sleek silhouette, plus a swirl of candy-colored design, and suddenly you’ve got the perfect whimsical product.

Another factor is nostalgia. Many of today’s parents grew up in the 1980s and ‘90s (hello, that’s me), an era ripe with unicorn imagery in toys, cartoons, and stationery. The unicorn is being handed down as a multi-generational icon, a comforting constant that can be reinterpreted with each successive cultural shift. Now, it fits neatly into a digital culture eager for eye-catching, shareable symbols.

Despite the creature’s commodification—one might even say domestication—the unicorn still carries a certain magic. A plush unicorn in a child’s bedroom might be festooned with plastic jewels and heart patches, but it also symbolizes a little piece of the impossible come to life. The allure is in the horn: that mysterious protrusion of power, said by centuries of myth to cure poisons or purify water. Even in plastic form, it winks at the ancient notion of a force beyond logic.

And for parents, there’s perhaps a quiet satisfaction in seeing their children embrace something that’s been a part of human imagination for millennia. Myths survive by evolving. The unicorn didn’t just find a place in children’s culture—it reinvented itself there. No longer confined to courtly tapestries or weighty biblical allegory, the unicorn now stands—glitter hoof and all—as an emblem of childhood whimsy that is, ironically, universal.

In this age of relentless digitization and instant gratification, the fact that a legendary horse with a single horn persists at all is a testament to the power of the imagination — and, perhaps, to our own penchant for holding onto a bit of mystery. Even as we affix it to pencil cases, T-shirts, and coffee mugs, the unicorn remains just elusive enough. And so, in bedrooms and playgrounds worldwide, the ancient and the modern gallop on, one glittery hoofbeat at a time.