Amid the fervent jazz revival that swept Paris in the years following World War II, a host of American musicians found a second home on the banks of the Seine. Paris became a cherished haven for many Black artists whose creativity often ran up against racial barriers in the United States. Although legends like Sidney Bechet, Nina Simone and Duke Ellington have long been recognized for their Parisian sojourns, one name that has slipped from popular memory is the trailblazing pianist and vocalist Hazel Scott. A significant force in the jazz world, Scott carved out a unique space in postwar France, captivating audiences with her virtuosic performances and elegant style. Yet, despite her past acclaim and the political bravery that cost her dearly in the American cultural sphere, Scott’s story in Paris remains overlooked. Before we continue learning about her rich legacy, perhaps it’s appropriate to hit play and sink into the sounds of Hazel Scott…

Originally from Trinidad and Tobago, Scott was born to a pianist and music teacher mother and a West African scholar father, two disciplines that would shape her own interests. Scott moved to Harlem, during the height of the neighborhood’s creative renaissance, at the age of four with her mother, Alma Long Scott, who was already aware of her daughter’s immense talent. She began working with Professor Paul Wagner at the prestigious Juilliard School of Music (she was so talented that it didn’t matter she didn’t meet the 16 year age requirement) and at 13 started playing piano and trumpet in her mom’s Alma Long Scott’s All-Girl Jazz Band.

Helped by family friend Billie Holiday, the teenage Scott became a regular feature on commercial radio and at Café Society, one of the hottest Greenwich Village nightclubs of the era, known for its strident racial equality when it came to both performers and customers. (It’s also where Holiday first sang “Strange Fruit.”) Critics were impressed by how she seemed to fluidly glide over the rigid boundaries of classical and jazz music, as a 1942 Time Magazine profile entitled “Hot Classicist” reads,

“But where others murder the classics, Hazel Scott merely commits arson. Classicists who wince at the idea of jiving Tchaikovsky feel no pain whatever as they watch her do it. She seems coolly determined to play legitimately, and for a brief while, triumphs. But gradually it becomes apparent that evil forces are struggling within her for expression. Strange notes and rhythms creep in, the melody is tortured with hints of boogie-woogie, until finally, happily, Hazel Scott surrenders to her worse nature and beats the keyboard into a rack of bones. The reverse is also true: into ‘Tea for Two’ may creep a few bars of Debussy’s ‘Clair de Lune.’ Says wide-eyed Hazel: ‘I just can’t help it.’”

With this “swinging the classics,” as she called it, Scott was soon playing with the biggest artists of her day, including the Count Basie Orchestra, Charles Mingus and Max Roach, and on Broadway. Traveling the world and becoming one of the highest-paid Black performers of her day, she refused to perform for segregated audiences. This was not a small request in Jim Crow America: The Cotton Club, one of the most renowned New York jazz venues, for a period only allowed white audiences.

It wasn’t long before Hollywood star makers saw Scott and wanted her for their pictures, but she would only do so on her terms. In her contract, she requested control over how she was portrayed and refused to play stereotypical Black parts, notably as a singing maid — a role she was reportedly offered four times. As she later wrote, “From Birth of a Nation, to Gone with the Wind, (…) from bad to worse and from degradation to dishonor — so went the story of the Black American in Hollywood.”

Refusing to compromise on her image only grew Scott’s celebrity as she played herself in five films (all made in a year and a half), including 1944’s Broadway Rhythm, with singer and actress Lena Horne, and Rhapsody in Blue, a 1945 biopic about composer George Gershwin. But her most memorable performance, clips of which continue to go viral today, is from 1943’s The Heat’s On, in which she wows, playing two pianos at once.

Take a look:

But she came to heads with Columbia Pictures head Harry Cohn over other Black actresses wearing dirty uniforms in a movie. While her three-day protest proved successful, Scott was given no more film roles, a taste of the pushback soon to come, and returned to New York’s music scene.

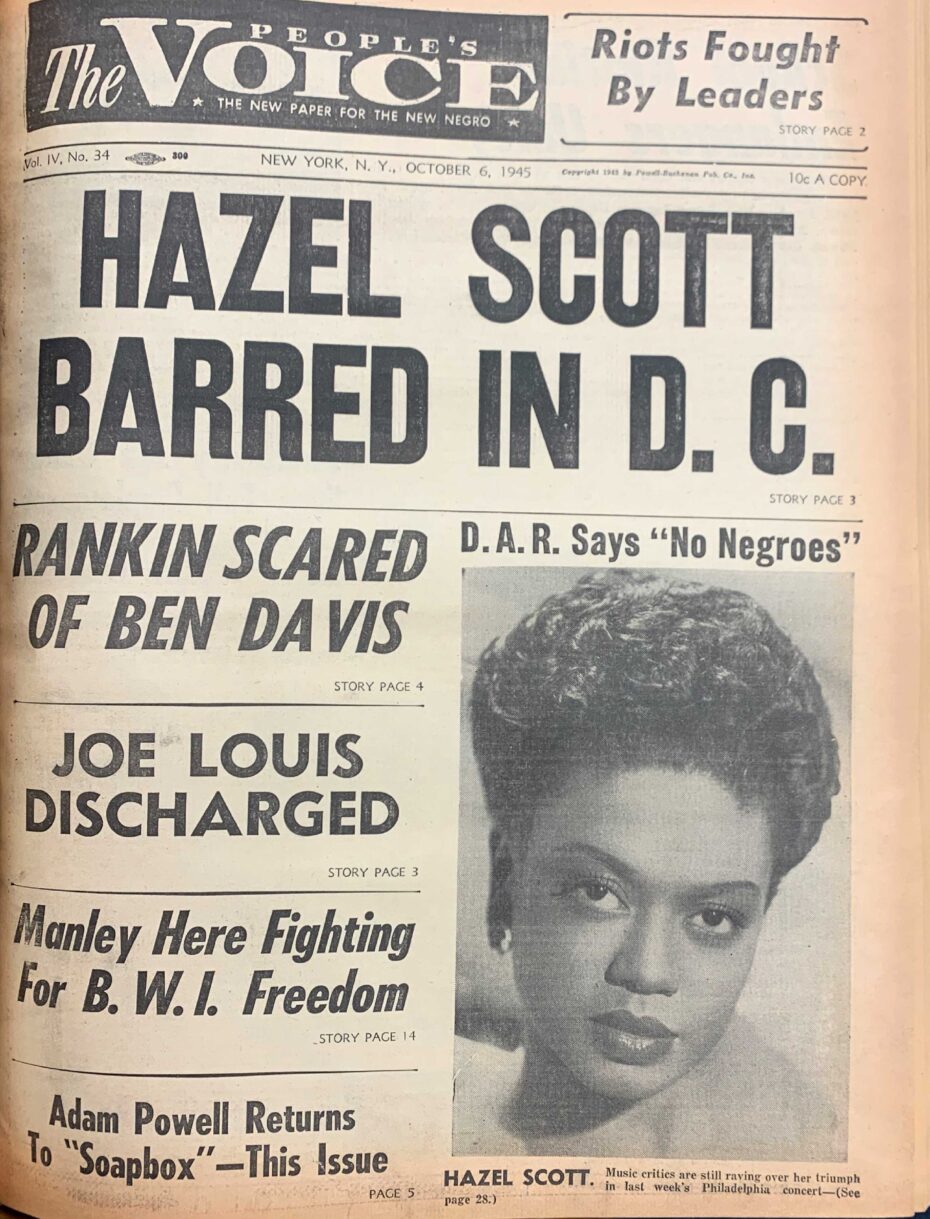

It was around this time that the FBI opened a file on Scott, noting her connections to the American Civil Liberties Union’s American Committee for the Protection of the Foreign and the Civil Rights Congress, which was connected to the Communist Party USA. The FBI also cited her recent marriage to Black Congressman Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., who would become a powerful figure within the Democratic Party. Scott too began gaining more media coverage for calling out racial discrimination, whether by the Daughters of the American Revolution or the National Press Club. She was even escorted by the Texas Rangers after refusing to play at a segregated venue in Austin. As she once said, “Why would anyone come to hear me, a Negro, and refuse to sit beside someone just like me?”

In the summer of 1950, Scott marked another breakthrough, becoming the first African-American woman to host a TV show with The Hazel Scott Show. During the 15-minute segments, Scott would perform tunes, hailed by Variety as a “neat little show in this modest package.” But despite a solid start in terms of viewers, it was canceled after just a few months. The reason? Scott’s name had just appeared on the Red Channels: The Report of Communist Influence in Radio and Television, a document by a right-wing journal listing some 151 entertainment and media figures who supposedly were trying to forward the Communist cause. (Others listed include Orson Wells, Dorothy Parker and Leonard Bernstein.)

Despite their fame, most people included in the Red Channels faced rapid blacklisting, and the only opportunity to clear their names was appearing before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and snitching on other apparent Communist sympathizers. Scott came before the HUAC in September 1950 and while she denied any link with Communism, ended her testimony with an appeal to the arts in a democratic society: “The actors, musicians, artists, composers, and all of the men and women of the arts are eagar and anxious to help to serve. (…) We should not be written off by the vicious slanders of little and petty men. We are one of your most effective and irreplaceable instruments in the grim struggle ahead. We will be much more useful to America if we do not enter this battle covered with the mud of slander and the filth of scandal.”

But the repression of McCarthyism took its toll and Scott suffered a mental breakdown in 1951. She eventually recovered, left her husband and like many Black artists and thinkers of the era, found a creative refuge in France. She acted in the French crime film Le désordre et la nuit and was part of a group of African-American expats including James Baldwin who took part in a Paris demonstration in support of the 1963 March on Washington. As Scott biographer Karen Chilton wrote in a Smithsonian Magazine article,

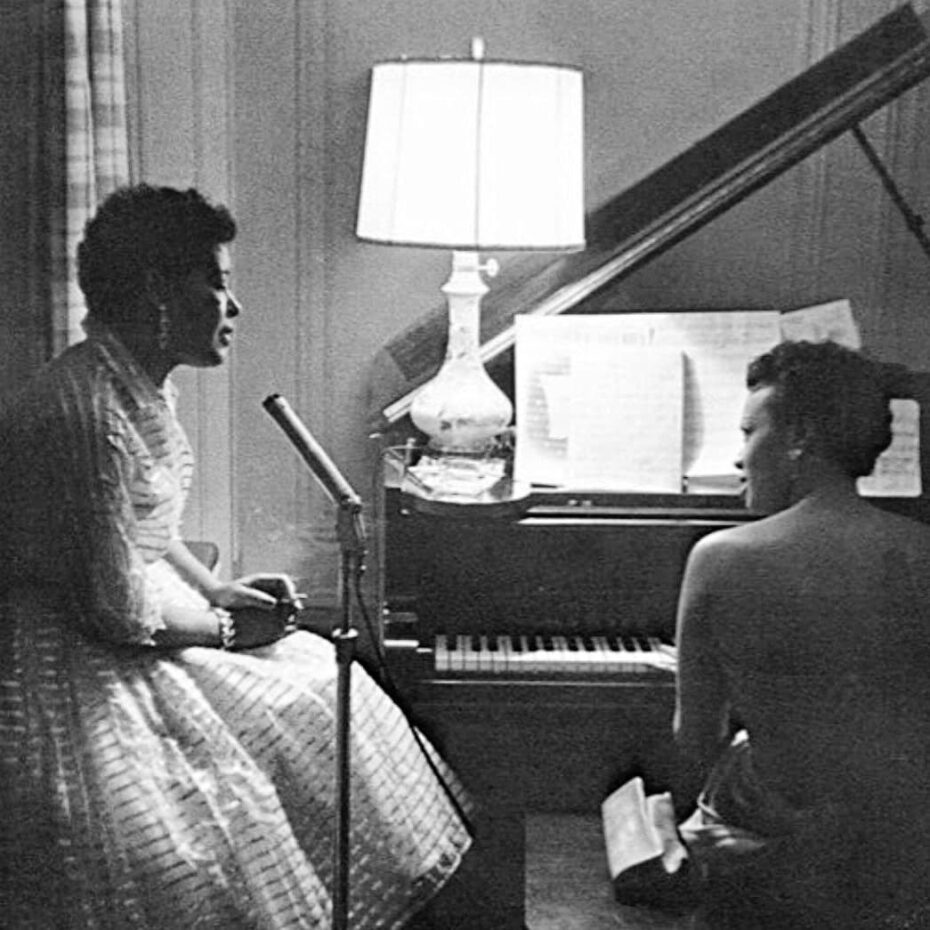

“Her apartment on the Right Bank became a regular hangout for other American entertainers living in Paris. James Baldwin, Lester Young, Mary Lou Williams, Dizzy Gillespie and Max Roach were regular guests, along with musicians from the Ellington and Basie bands. Hazel’s music softened during the Paris years; she played more serene tunes with less and less of her old boogie-woogie style.”

She eventually returned to the United States in 1967, when the work of the civil rights movement had resulted in major social advances. She continued to perform in nightclubs and even acted in the soap opera One Life to Live. She also joined the Bahá’í Faith, inspired by her friend and famed jazz trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie. Sadly, she passed away from cancer at just 61 in 1981.

Without a doubt, Scott would have risen to even greater prominence if it weren’t for her activism, but her legacy both as a musical genius and a woman of color who refused to compromise on her values provides inspiration to this day. Alicia Keys shouted her out at the 2019 Grammy Awards, she was the subject of a 2022 ballet by the Dance Theater of Harlem and a documentary about her is forthcoming.

While Scott always stated she didn’t wear “the activist’s tag,” as an immigrant she declared herself an American “by choice.” Her patriotism was clear in her pride for her identity: “I believe America is as big and as strong as its weakest point (…) it is up to the Negro to be the conscience of this great land of ours.”