I have a rather curious new addition to the Cabinet and I’m waiting for that one in a million collector or historian to walk in the door and geek out over it with me – with any luck, they might be able to reveal more secrets about this obscure piece of antique machinery known as a “lanterne magique” (magic lantern), or better yet, help me get it working. However until then, it’s a rather bulky looking thing that raises a few eyebrows of passersby, falling short of being appreciated not only as a direct ancestor of the motion picture projector, but as a key instrument of the earliest form of horror storytelling, known (quite fabulously) as phantasmagoria!

In a dimly lit Parisian salon at the close of the eighteenth century, a flustered group of thrill-seekers took their seats upon rickety chairs and nervously awaited a spectacle both shocking and exquisite—an evening’s entry into the world of phantasmagoria. The hush fell, the lamps were extinguished, and a single magic lantern began to glow. A creaking hinge, the crash of thunder, and then—whoosh!—a ghastly specter soared across the makeshift screen, seeming to come alive in the gathering haze. It was more than just a parlor trick; it was a kind of theatre that promised both intellectual insight and unadulterated horror, all under the auspices of scientific inquiry and cunning stagecraft.

Though its name and most celebrated practitioners hailed from Enlightenment-era Paris, phantasmagoria boasted far older antecedents. In medieval times, ambitious conjurers—more necromancers than entertainers—were said to deploy concave mirrors and rudimentary lanterns in clandestine ceremonies.

Whether they were truly hoping to conjure gods, demons, or apparitions of long-deceased ancestors is lost to history, but these shadowy demonstrations of “real” magic were certainly the forerunners of the great spectral stage shows to come.

By the early 1700s, the magic lantern — an optical device that projected images painted on glass slides—began to make its way into fairgrounds and traveling sideshows. In Paris and beyond, wandering conjurers known as “Savoyards” (purportedly from the Savoy region of France) lugged these bulky contraptions from town to town. Their repertoire was a hodgepodge of folk tales, street performing, and illusions. A Savoyard might sing ballads, juggle, or recite bizarre stories, then produce, from a battered trunk, a magic lantern that could beam devilish illustrations onto any surface. While the images themselves were rarely life-like — crude devils, skeletons, or comedic caricatures — they nonetheless turned a mundane inn-yard or tavern corner into an ethereal spectacle.

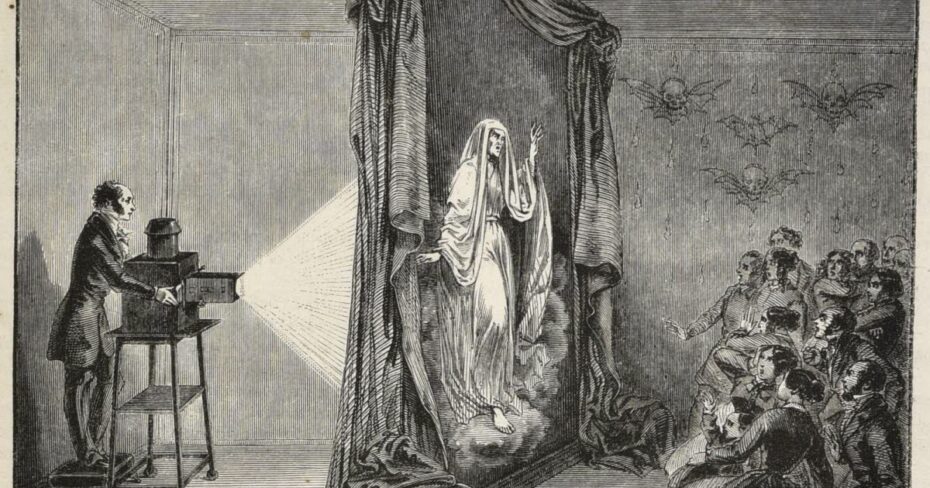

The golden age of phantasmagoria properly dawned in 1790, in the tumult of pre-Revolution Paris. An enigmatic magician and self-styled “physicist” named Phylidor (also known as Paul Filidort) presented what may have been the first bona fide phantasmagoria show. With a flair for irony, Phylidor marketed his sorcery as a method of exposing the very trickery he practiced — he claimed to unmask the charlatans, revealing how illusions of ghosts and apparitions could be conjured through optics and chemical wizardry. Audiences marveled at the interplay of rational explanation and ghoulish spectacle, awarding Phylidor a reputation as both an impresario of dread and a champion of reason.

Yet for all Phylidor’s innovation, it was Étienne-Gaspard “Robertson” Robert who would come to embody phantasmagoria in the public mind. A Belgian-born showman (though Paris quickly claimed him), Robertson perfected the form with a spectacular device he dubbed the “fantascope,” effectively a refined magic lantern that allowed for such dramatic possibilities as sliding images, superimposing shapes, and even passing the beam through swirling smoke. Rumor has it he once went so far as to enhance the terror by exposing unsuspecting patrons to small electric jolts or herbal concoctions meant to heighten their senses, but the insinuation that he might have have drugged his audience may be half urban myth, half eighteenth-century marketing ploy.

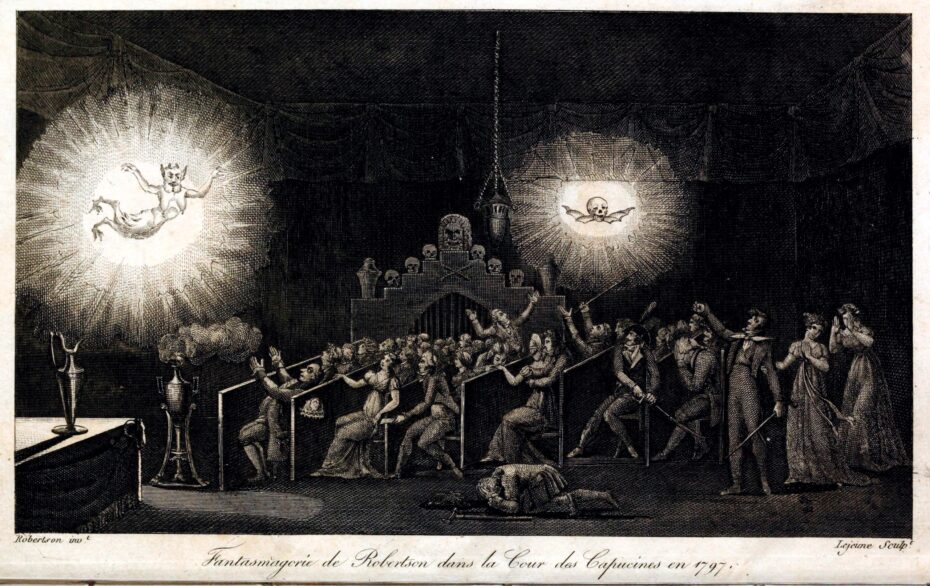

Nonetheless, what truly set Robertson apart was his meticulous attention to atmosphere. He would plunge his audience into complete darkness for extended intervals, then abruptly reveal ominous figures—skeletons, ghosts, grinning devils—seemingly hovering in midair. He was known to lock the theatre doors at the start of each performance, ensuring that no one could flee once the phantasmagoria was underway (or, some might argue, once they realised their own terror). Thunderclaps rattled the rafters; ghostly moans emanated from unseen corners; bells tolled with disarming suddenness.

One of Robertson’s earliest triumphs, in 1797, unfurled inside the Pavillon de l’Échiquier in Paris. Attendees found themselves gazing at a turbulent sky shot through with lightning, ghosts darting forward and back with uncanny verisimilitude. So convincing were his illusions that the police, fearing Robertson might actually possess the occult power to resurrect the recently executed Louis XVI, temporarily shut him down. In the post-revolutionary fervor—when apparitions of the monarchy had a certain political electricity—his illusions struck terror into more than just the average playgoer.

Robertson did not miss a beat; within a short span, he relocated his show to an abandoned cloister’s kitchen near the Place Vendôme. To heighten the dread, he decorated the space like a subterranean chapel. Dank walls flickered with disembodied faces, and the echo-laden corridors amplified the faintest sound into a diabolical roar. For six years, Parisians flocked to this ghoulish attraction, reeling not just from the illusions, but from the city’s own battered psyche after the Revolution’s upheavals. In that charged moment, illusions of haunting and redemption, of returning specters in the catacombs of an ancient chapel, felt unnervingly real.

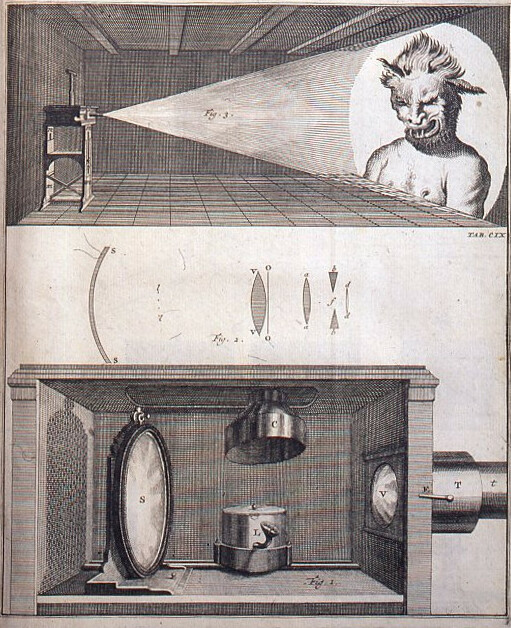

Beneath the smoke-and-mirrors of Robertson’s theatrics lay the modest but ingenious magic lantern – as mentioned, a direct ancestor of today’s motion picture projector. At its most basic, the device projected a single glass slide. But with a bit of ingenuity, it could suggest motion by flipping between slides depicting slightly different phases of an action, akin to a rudimentary flip-book. The more sophisticated approach involved using two overlapping slides simultaneously—one stationary, one capable of movement (thanks to a simple hand crank or lever). A devil might wag its tail or a skeleton’s jaw could chatter, each miniature movement magnified into startling realism on the big screen.

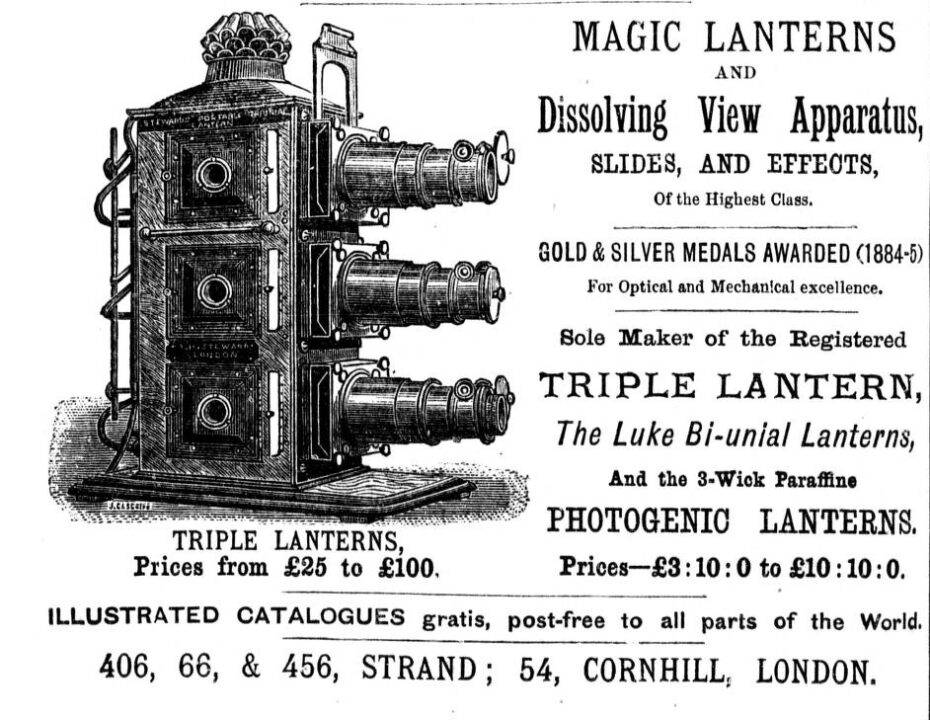

By 1860, production of magic lanterns had become cheaper, making these arcane amusements more accessible to a broad swath of the public. Families across Europe and North America purchased “home lanterns” to project pictures on their parlour walls — an entertainment that presaged the living-room TVs and home movie projectors of the twentieth century. But when the cinema revolution arrived in the 1890s, with images that truly danced, blinked, and laughed in real time, the magic lantern’s hold on the public imagination began to wane. Still, the device endured for educational slideshows and amateur theatrics for decades, with some households clinging to its wonders until slide projectors finally dominated in the mid-twentieth century.

And so the phantasmagoria, born in medieval mystery, honed in the feverish atmosphere of revolutionary France, faded like a ghost at dawn. Yet its afterglow remains, preserved in each flicker of a modern projector. The darkened auditorium, the hush that settles, the communal feeling of trepidation and delight: these are the direct descendants of nights spent cowering before Robertson’s dancing skeletons. That long-lost age of conjurers and necromancers was, in truth, the first cinematic experience— the moment we realised we could tell stories in light and shadow, and that an illusion could grip an audience harder than any polished reality.

Today, the memory of phantasmagoria might seem quaint or outlandish. We know what films are now. We have digital screens, high-definition clarity, and streaming platforms available at the touch of a button. But even in our thoroughly modern world, the thrill persists. Lurking, perhaps, in the corner of our collective imagination is that smoky hall in Paris: the hush, the thrill of the unseen, and the conjurer, sliding glass plates through a fantastical lantern—inviting us to confront our deepest fears, or, at the very least, to marvel at how willingly we surrender ourselves to the dance of light and shadow. Do come and marvel at my lanterne magique chez Messy Nessy’s Cabinet in Paris today. And I promise not to drug you or lock you inside, of course! I’m hoping one of these days, I might find the time to tinker with it and get it going to host our own modern-day phantasmagoria soirée.