Sex and botany– two words rarely found in the same sentence, but there was a time when the study of botany was considered so obscene that books on the subject were censored for women; branded dangerous and unsuitable for her delicate sensibilities. Gardens and greenhouses became an enlightened woman’s secret haven of discovery, expression and temptation. While today’s scientific world might have lost sight of the romance, once upon a time, botany was the most provocative and desirable virtuosity of the enlightenment era.

So what could possibly be so sexy about botany? In the 18th century, a new wave of botanists began confirming the theories of the ancients, that flowering plants do indeed have “sex” to reproduce, using their female and male organs, going as far to compare the stamen to a penis, the style to a vagina, even the plant petals to a bed and the leaves to the bedroom curtains.

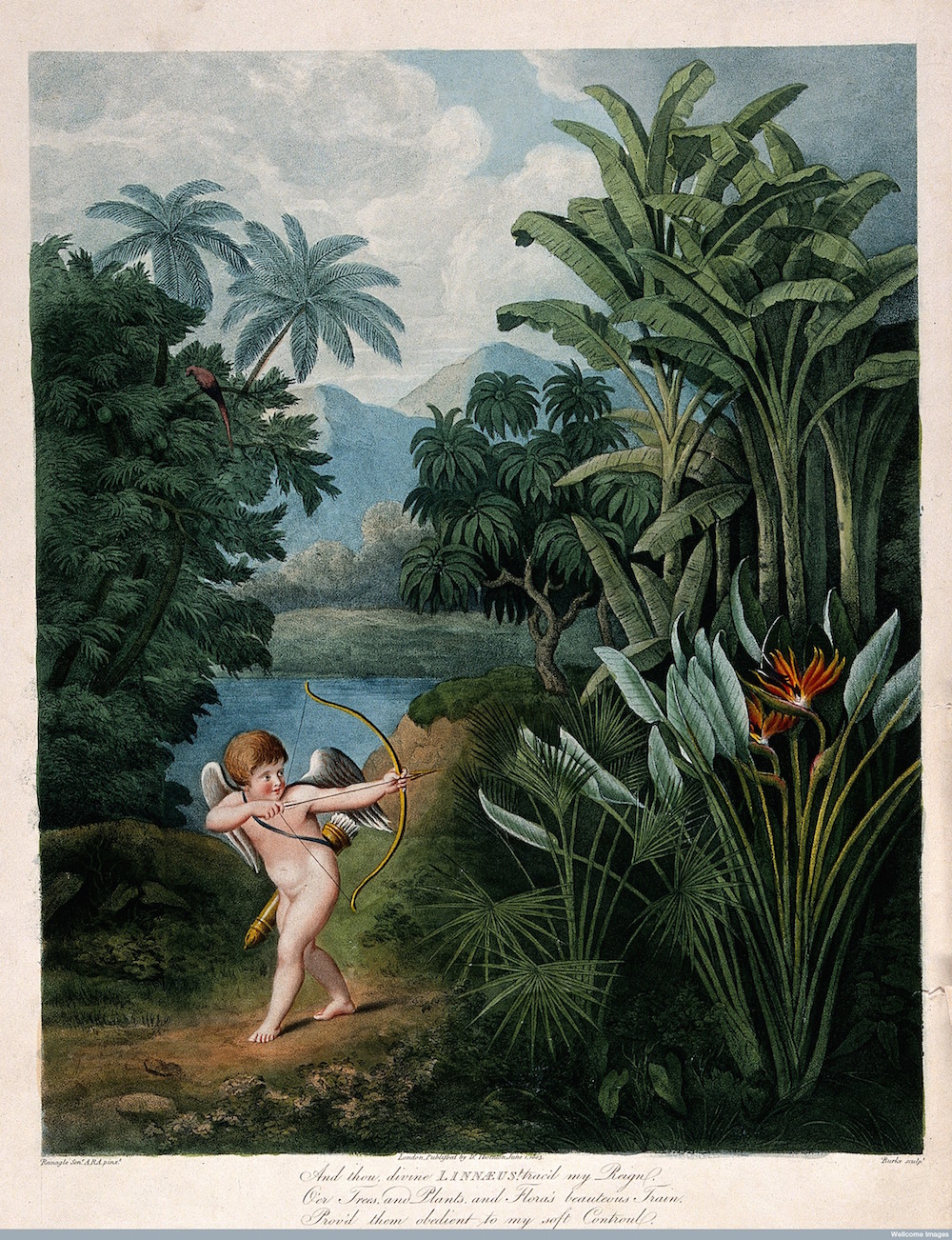

In his two-volume work, Species Plantarum (1753), Carl Linnaeus, a Swedish botanist, physician, and zoologist, identified pollen as the impregnating male sperm, and described female plants as either widows or virgins. Despite using metaphors of marriage and monogamy, he also argued that some female plants can only be impregnated by pollen carried “promiscuously” in the wind. It was taught, that much like women and animals, flowers give off a seductive scent when they’re ready to mate, triggering the birds and the bees, as well as butterflies to join in on these rites.

Such libertine and oversexed ideas shocked conservative society who labelled it “loathsome harlotry” that something “the Creator of the vegetable kingdom” would never have allowed. The rest of society however, was fascinated.

Inspired by Linnaean’s controversial teachings, Charles Darwin’s grandfather, Erasmus, wrote The Loves of the Plants, in 1791, a poem which brought botany to the masses, making it interesting and relatable. This poem served as many a young lady’s guide to discovering her own sexuality (and man’s). Darwin revisited comparisons of plant reproduction and wedding nuptials, capturing the imagination of curious and impressionable young women awaiting marriage. While simultaneously raising anxiety surrounding female modesty, botany emerged as one of the most intriguing topics of the Enlightenment.

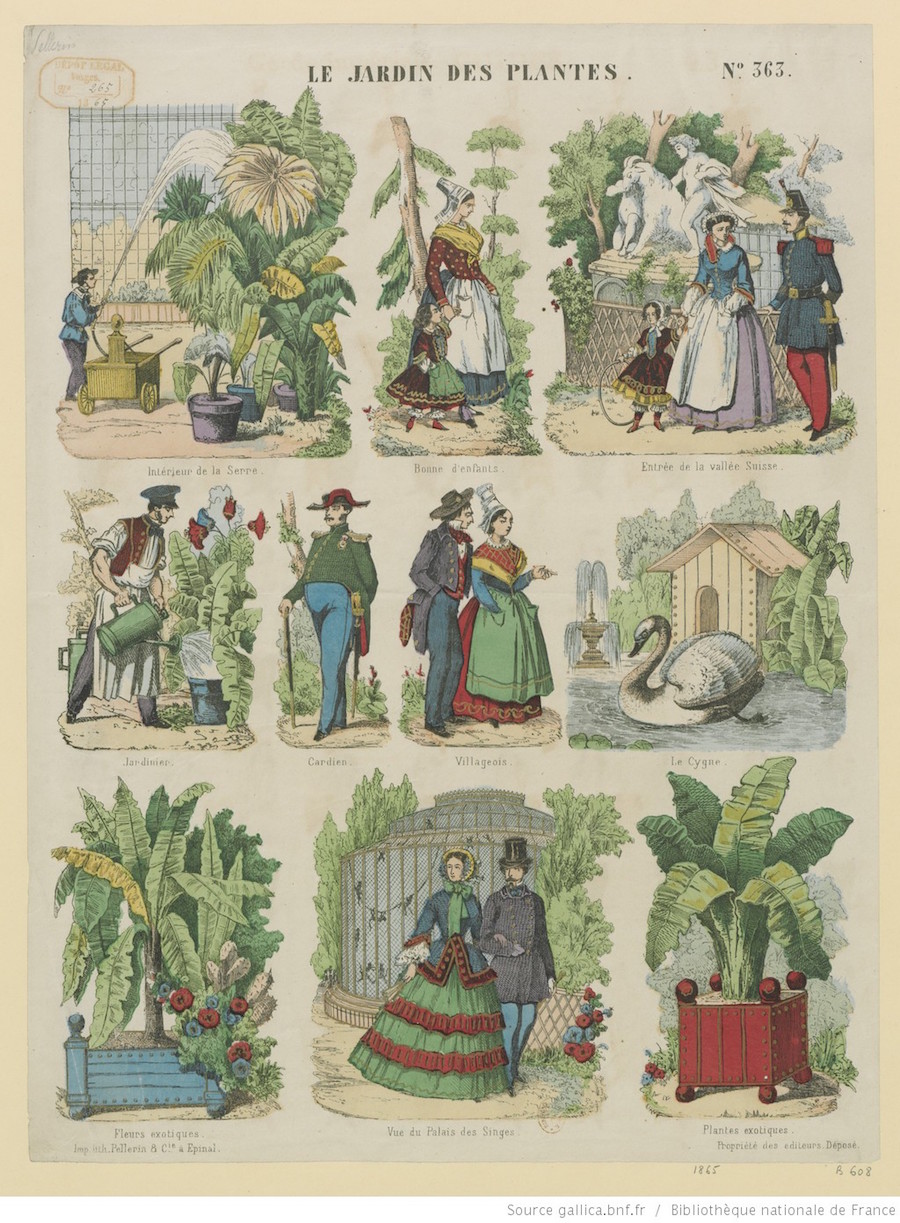

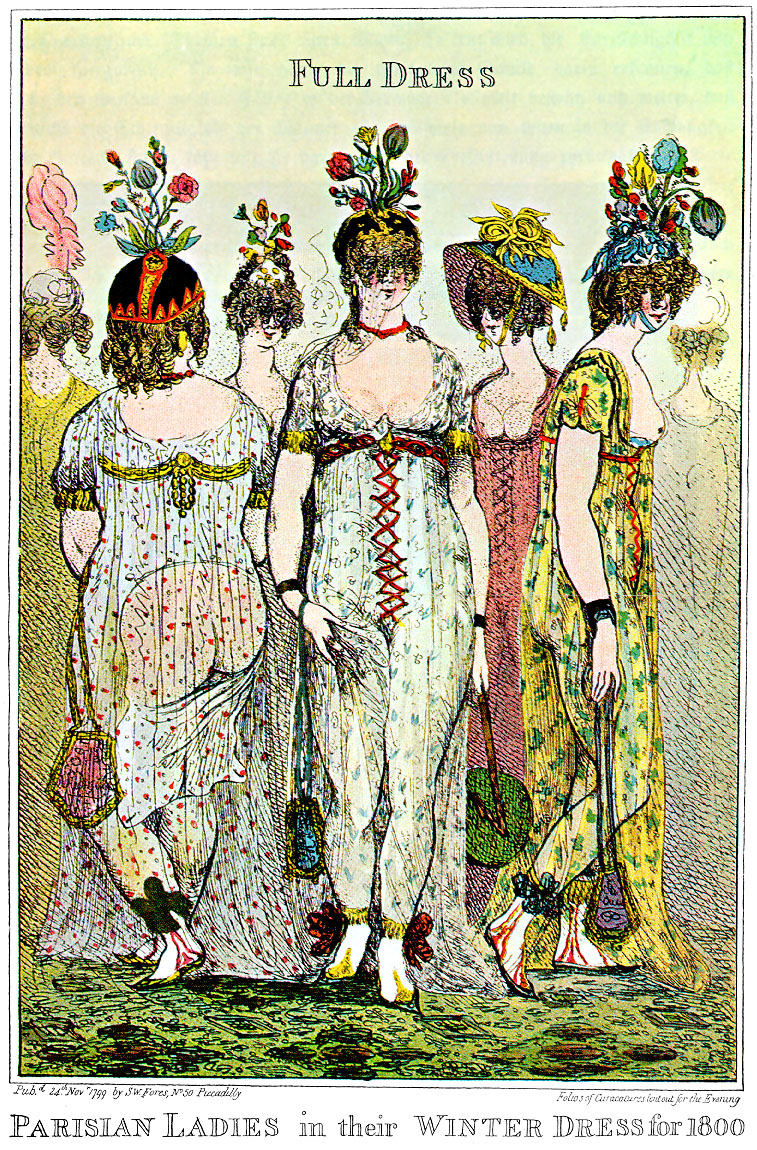

Society’s religious figures warned that botanising girls who showed interest in exploring the sexual parts of the flower, were “indulging in acts of wanton titillation”– just the sort of thing to fuel any female libertine’s fire. As Linnaean ideas spread in the revolutionary climate of the 1790s, women’s botany became more and more fashionable and there was an enormous growth in the number of botanical and horticultural books. Queens and Princesses were instructed in botanical drawing and plant collecting. Gardening became a highly desirable past time, encouraged by fashionable ladies magazines and periodicals. Women’s clothing began to reflect the rising interest in botany and floral designs dominated fabrics and silks of the 18th century. Soon enough, society’s most fashionable women started to look like walking botanic gardens. The greenhouse even became her beauty boudoir where she could pick out accessories for a growing fad in hair fashion that involved putting anything from fruits, shells, artificial birds to miniature flower gardens in their headdresses. An English philanthropist of the day, Hannah More wrote, “I hardly do them justice when I pronounce that they had, amongst them, on their heads, an acre and a half of shrubbery … grass plots, tulip beds, clumps of peonies, kitchen gardens, and greenhouses.”

Such extravagance of taste was the subject of a number of satirical prints and engravings featuring preposterous coiffures. A new stereotype of the forward, sexually precocious, female botanist emerged in the turbulent revolutionary climate of the 1790s.

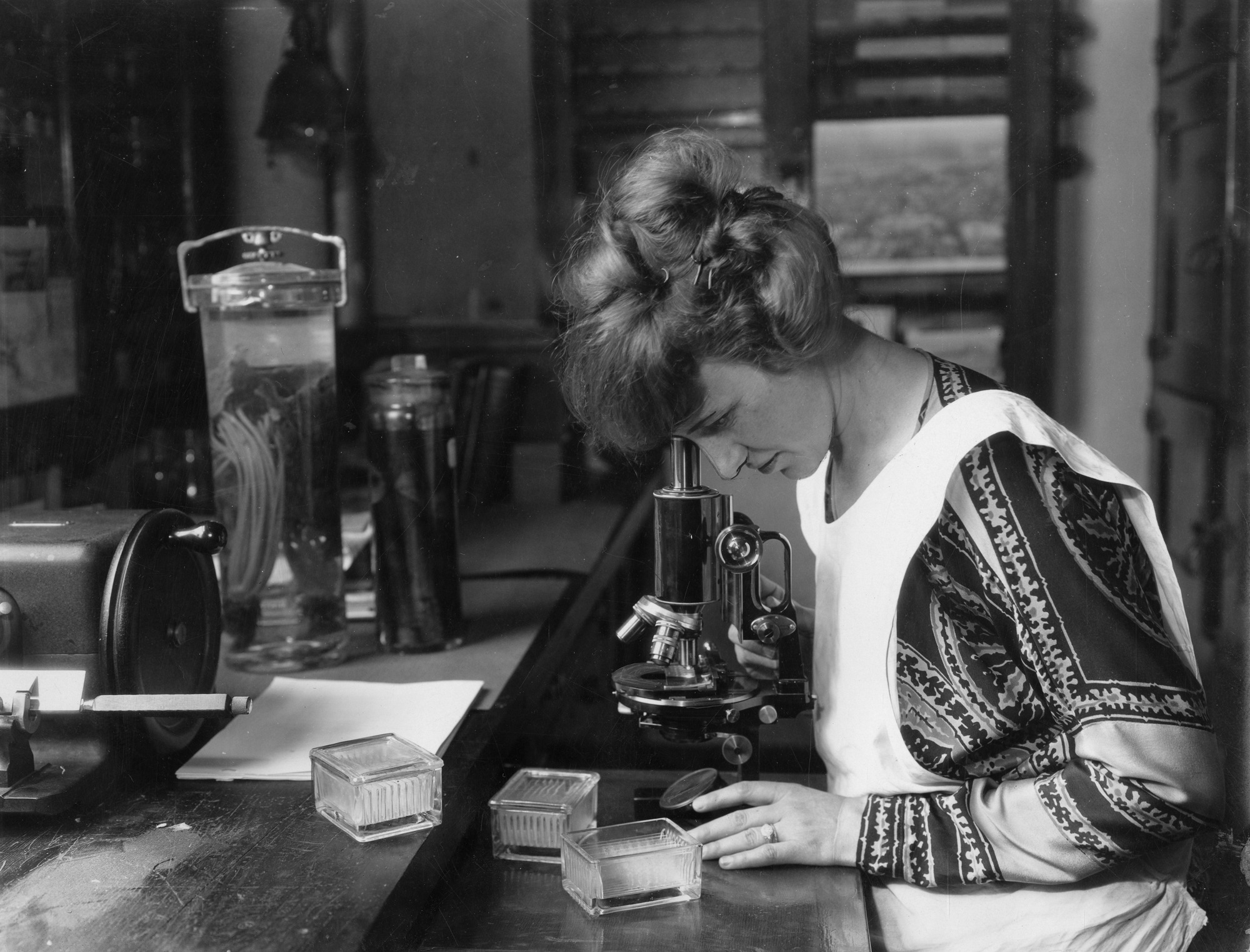

Botany, one of the few sciences open to women which could be conducted without handling weapons or killing animals (seen as a male domain), had gone from being a reputable and chaste enterprise for women to suddenly becoming dangerous. An innocent pastime for genteel ladies was suddenly brewing a feminist movement that was making a male-driven society very uncomfortable.

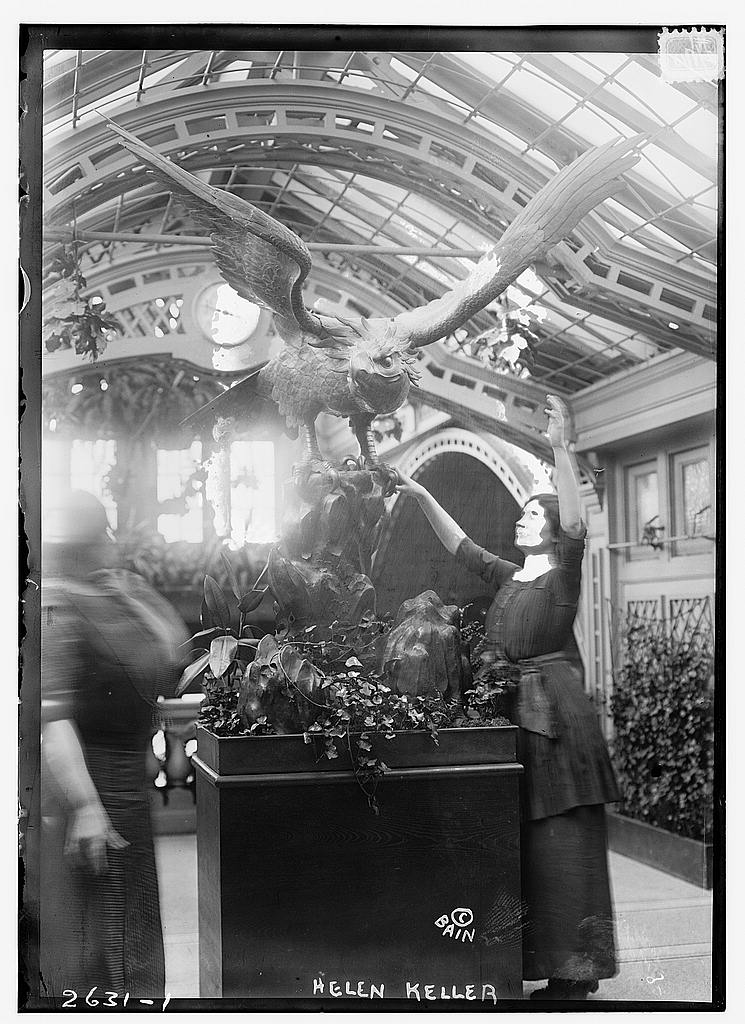

At the same time, it was coinciding with a growing spiritualist movement in Victorian society, and botany was closely linked with superstitious beliefs in exotic medicinal plants being introduced to Europe by colonial explorers. The romantic era for botanical exploration brought stories of tribal medicine men or women and their healing powers. In 1910, a female writer published “The Secret Garden”, exploring the spiritual power of nature’s gardens.

Religious leaders didn’t like the direction that botany was heading and by the early 19th century, there was a strong counter movement underway to censor botanical textbooks from women. It was deemed improper for the female pen, effectively silencing their voice on the subject. Botany, as it was known in the enlightenment, became a lost and repressed passion for women … almost.

Debating the Linnaean sexual system had become unacceptable and literary women began struggling to even share their voice on the subject that was deemed improper for the female pen. Women botanists were denounced, and the sexual botanical texts of Linnaeus and Erasmus were rigorously suppressed. While Erasmus’ grandson, Charles Darwin would later turn these ideas about sexual reproduction in the natural world into a full-fledged theory of evolution, botany, as it was known in the enlightenment, became a lost art and a repressed passion. Today, it is widely considered as one of the most sanitised, conservative and mundane subjects the world of science has to offer. But inside those historic Victorian greenhouses, there’s mystery and magic in the heavy, wet air; whispers of an enchanting era in time when stars aligned to produce a wave of botanical romance and intrigue.