In the copper-mined heart of late 1960s Zambia, a new sound was brewing — raw, electrifying, and entirely unexpected, channeled the sounds of Hendrix, Sabbath, and Cream through the lens of life in a newly independent African nation. It was called Zamrock, a genre that fused the fuzzed-out guitars and rebellious spirit of Western psychedelic rock with traditional African rhythms and post-colonial urgency. At once a product of its time and decades ahead of it, Zamrock is now being rediscovered by vinyl collectors, music historians, and curious ears around the world. It’s loud. It’s gritty. It’s soulful. And it’s one of Africa’s best-kept sonic secrets.

1964 was arguably the most important year in popular music, with the British Invasion taking

over the airwaves on both sides of the Atlantic. But in newly independent Zimbabwe, President

Kenneth Kaunda was implementing a controversial radio strategy that would result in a totally

original musical genre: Zamrock. As part of his “One Zambia, one nation” policy, President Kaunda ordered that 95% of the music on radio stations be of Zambian origin. Already in the 1950s, the landlocked African country had a burgeoning music movement coming from its northern Copperbelt Province, with musicians like John Lushi, William Mapulanga and Stephen Tsotsi Kasumali producing tracks about societal issues. These artists, who came from the various Zambian kingdoms brought together under colonialism, exchanged musical styles and combined traditional instruments like the

vimbuzza drum and kalimba hand piano with the guitar and accordion, brought by the British

colonizers.

The vision of artistic patriotism promoted by President Kaunda, who himself played music as a

hobby, was aided by the newly founded Zambia Broadcasting Service, which “led a drive to

focus on domestic musical talent and made a concerted effort to collect Zambia’s ceremonial,

festival, and work songs nationwide,” as the Guardian wrote in an article about Zamrock.

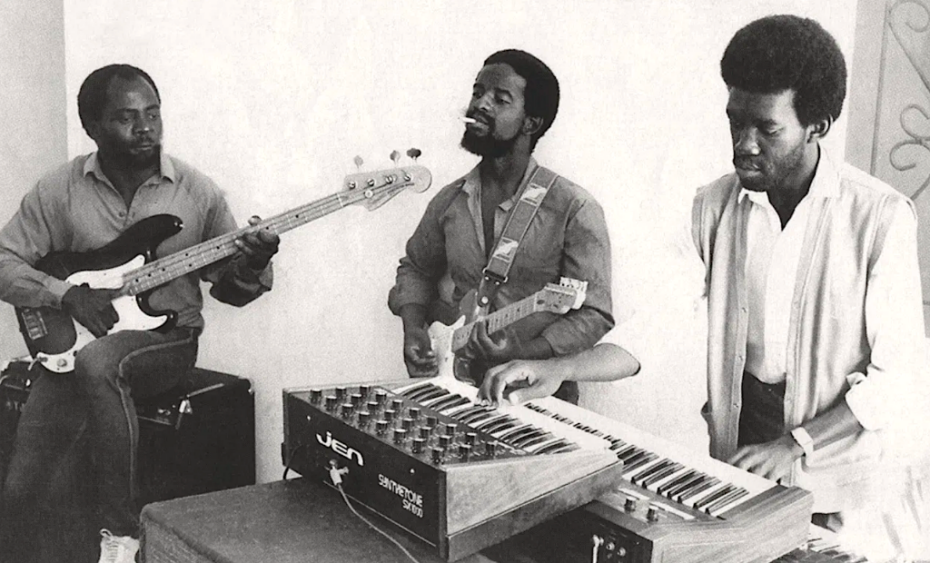

Concurrently, rapid urbanization and economic growth in the copper-rich former colony led to a

rise in the electric guitar as the instrument de jour. And despite domestic radio restrictions, many

young Zambians tuned into what was coming out of British stations and honed their musical

skills through learning covers. Rikki Ililonga and his band Musi-O-Tunya (meaning “the smoke

that thunders” in Tonga) are regularly credited with helping create Zamrock. Musi-O-Tunya was

inspired by Afro rock group Osibisa (with members of British, Caribbean and Ghanaian origin)

and began refining its sound in the early 1970s before releasing its debut album Wings of Africa

(recorded in Kenya). Illilonga, who would go on to have a successful solo career, sang in English

as well as local languages including Silozi, Chinyanja and Ichibemba, reflecting the cultural

mixing.

This musical fusion is present on tracks like the 1975 single “Tsegulani,” in which African

drums are punctuated with sharp horns and fuzzy electric guitar. As Pop Matters writes, “the

mood is more Afrobeat than James Brown,” a reference to Nigerian artist Fela Kuti, who shaped

the African genre, and the American singer. While by the mid-1970s, Brown’s soul sounds, as

well as British psychedelic and hard rock, were more and more out of vogue in the West, what

became the Zamrock genre gave them renewed verve, most notably in one of its most famous

groups, Witch.

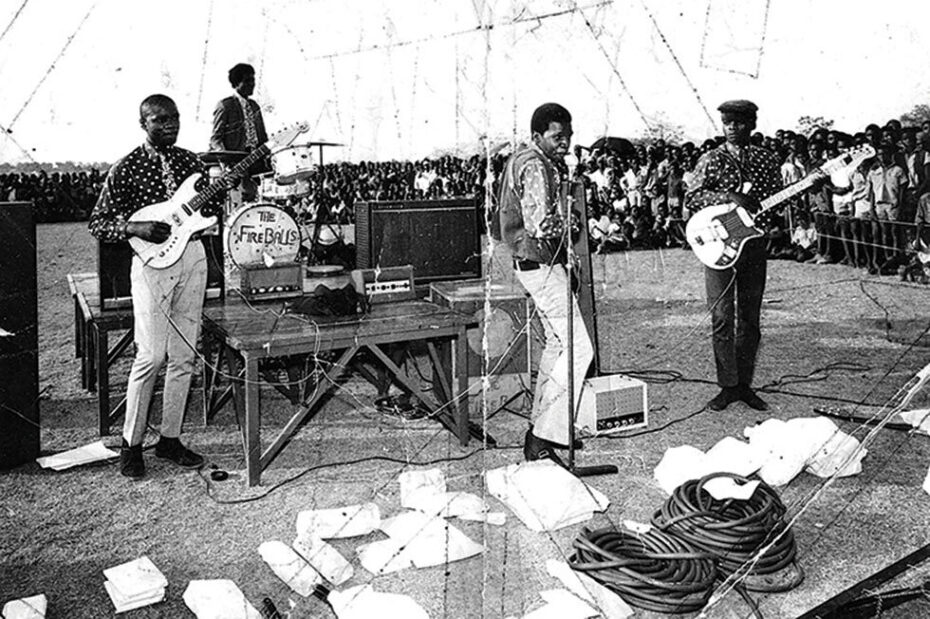

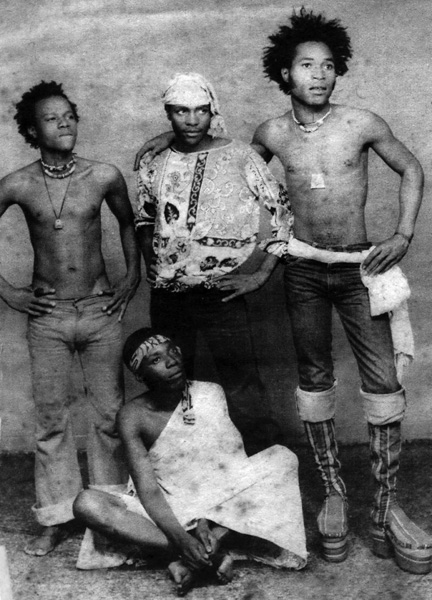

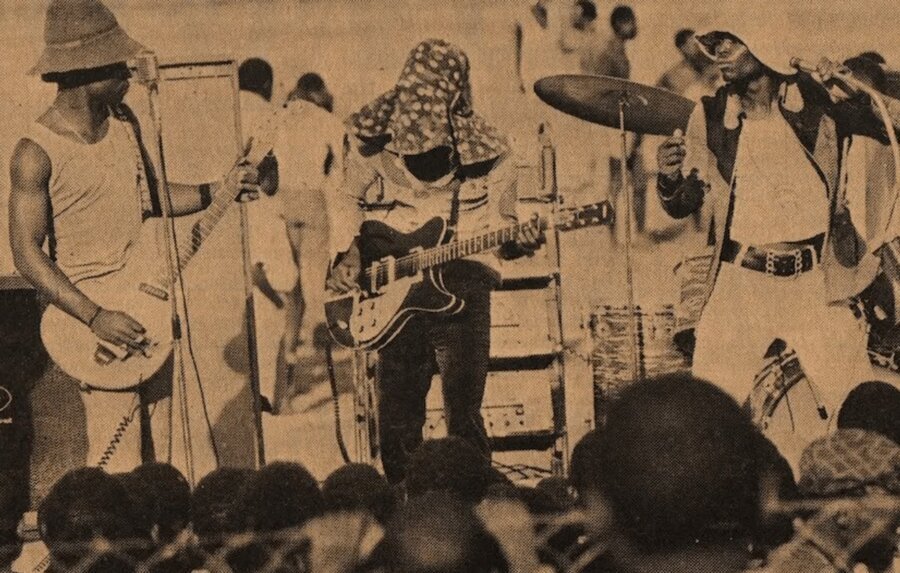

Around the same time as Musi-O-Tunya, Witch (short for We Intend To Cause Havoc) was

being influence by the likes of Jimi Hendrix and the Rolling Stones (lead vocalist Emanuel

“Jagari” Chanda took his name from Mick Jagger). The driving force behind Zamrock, Witch put

out some five albums in the ‘70s and toured neighboring countries. Chanda remembered this

heyday in a 2021 interview with the Guardian: “Sometimes we started at 7 o’clock and [played]

until 2 o’clock the following morning. Other times I threw a guitar into the crowd during the

show, and before it landed it was torn to pieces. Sometimes I wore ladies’ panties on top of my

trousers.”

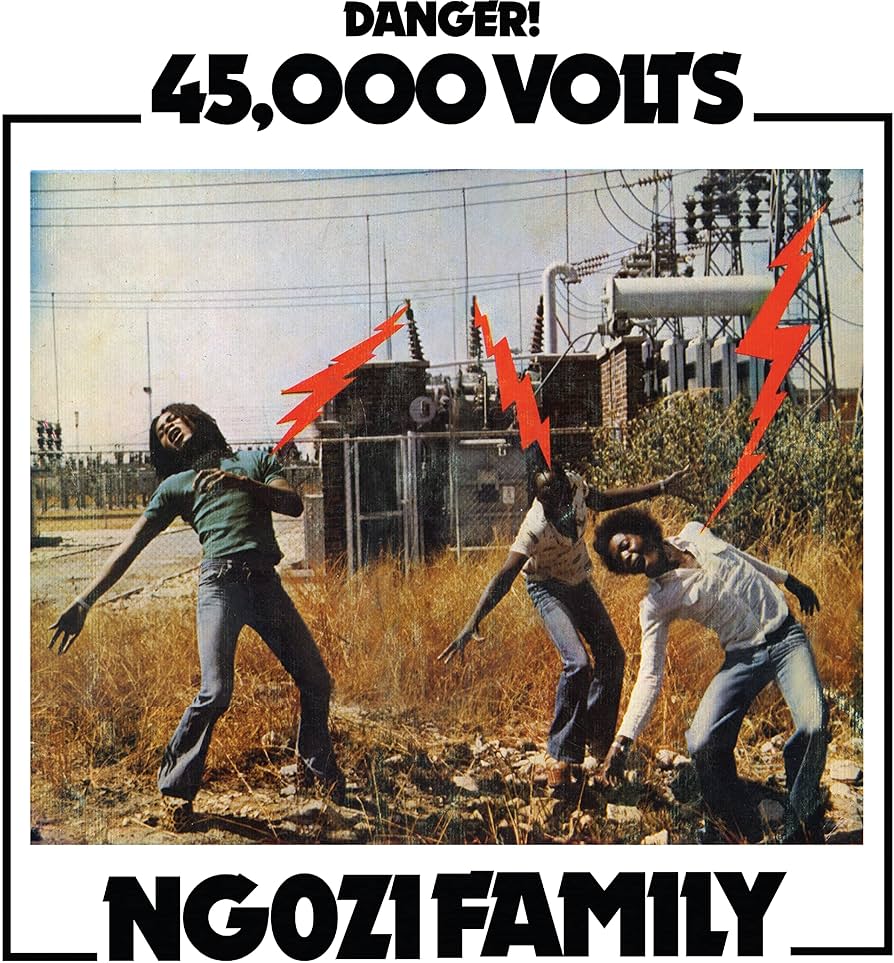

Witch may have been the Beatles of Zambia, as the Guardian described them, but they were

surrounded by a full “Invasion.” These included Paul Ngoz of the Ngozi Family band, credited

with creating a unique rhythm sound with the kalindula, a kind of bass guitar. The Peace, whose

lyrics unsurprisingly touched on the very ‘60s topics of love and freedom (one of their most

memorable songs is “Black Power”). And AMANAZ, an acronym standing for “Ask Me About

Nice Artistes in Zambia. AMANAZ only released one album, 1975’s Africa, but it continues to

pop up today: Tracks were featured on the series High Maintenance and Ted Lasso and rapper

Travis Scott featured the track ”Nsunka Lwendoé in his 2023 song “Sirens.” As Pitchfork wrote

in a review of its 2010 reissue, “They sound like a band that wanted to ply their trade in heavy

rock, folk-pop, and funk all at once– but there’s a rawness on this album that gives it a familiar

garage-band appeal.”

Sadly, this musical heyday would prove short as copper prices fell and those of oil rose, leading

to a recession. Records had already been an expensive commodity and became even more

inaccessible, as bands were also forced to lower the price of concert tickets. This economic

turmoil turned to social unrest, with restrictions extending to the music industry: Bands were

only allowed to perform day shows due to curfews. The final blow for the genre came with the

advent of HIV/AIDs, which killed 13% of the country’s adult population. Every original member

of Witch died of AIDS besides Emanuel “Jagari” Chanda. But like many musicians, he was

forced to abandon creative passions, taking up a career in mining.

This could have been the end of Zamrock, if not for an unexpected resurgence of interest that

came in the 2010s, first with a collective reissue from Now and Again Records and then two

documentaries: 2013’s Rikki and Jagari: The Zamrock Survivors and 2021’s WITCH: We Intend

to Cause Havoc, in which filmmaker Gio Arlotta traces what happened to the group. When

journalists came knocking, Chanda, now in his 70s, was more than happy to recount stories of

this glory period but also to prove his musical days were not behind him. He reformed Witch,

releasing an album in 2023 (his first in over four decades) and performing shows around the

world in his signature eccentric hats. He’s also inspired a new generation of musicians, notably

Zambian rapper Sampa the Great, who told the New York Times that she appreciates the

“defiance and the edginess” of Witch’s music. Chanda doesn’t seem to be stopping anytime

soon, with a new album, SOGOLO, coming out in June.

As he told a crowd during a 2024 East London show, “Like the story of the phoenix, the bird

from the ashes. Zamrock has resurrected from its decades of slumber,” before letting the funk

take over.